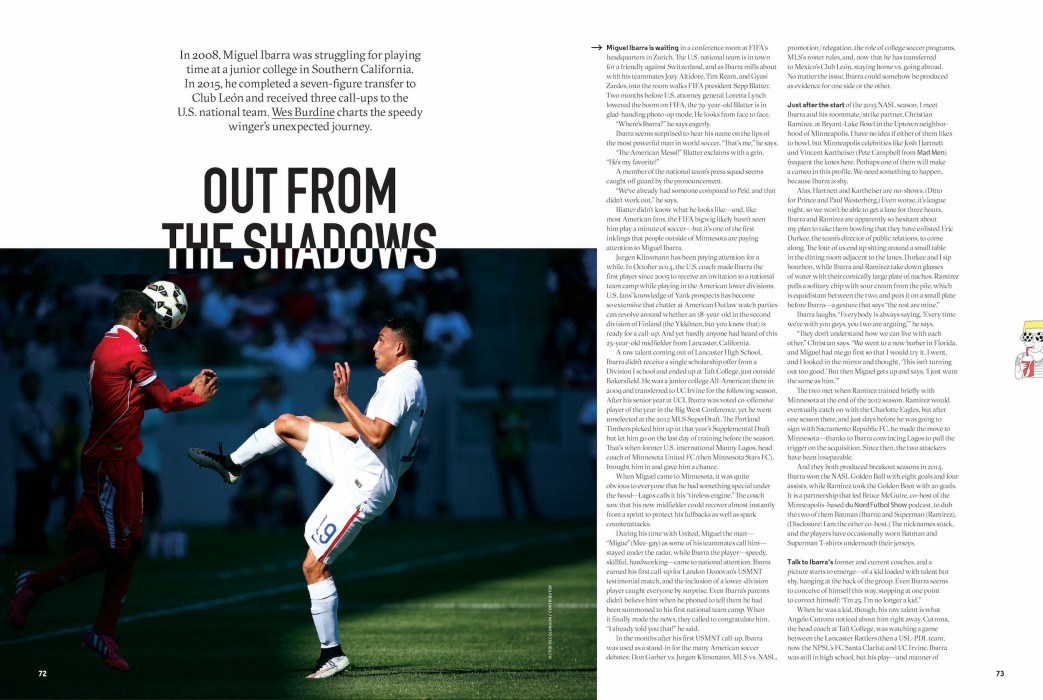

In 2008, Miguel Ibarra was struggling for playing time at a junior college in Southern California. In 2015, he completed a seven-figure transfer to Club León and received three call-ups to the U.S. National Team. Wes Burdine charts the speedy winger’s unexpected journey.

Editor’s note: This story first appeared in Howler Issue 09

Miguel Ibarra is waiting in a conference room at FIFA’s headquarters in Zurich. The U.S. national team is in town for a friendly against Switzerland, and as Ibarra mills about with his teammates Jozy Altidore, Tim Ream, and Gyasi Zardes, into the room walks FIFA president Sepp Blatter. Two months before U.S. attorney general Loretta Lynch lowered the boom on FIFA, the 79-year-old Blatter is in glad-handing photo-op mode. He looks from face to face.

“Where’s Ibarra?” he says eagerly.

Ibarra seems surprised to hear his name on the lips of the most powerful man in world soccer. “That’s me,” he says.

“The American Messi!” Blatter exclaims with a grin. “He’s my favorite!”

A member of the national team’s press squad seems caught off guard by the pronouncement.

“We’ve already had someone compared to Pelé, and that didn’t work out,” he says.

Blatter didn’t know what he looks like — and, like most American fans, the FIFA bigwig likely hasn’t seen him play a minute of soccer — but it’s one of the first inklings that people outside of Minnesota are paying attention to Miguel Ibarra.

Jurgen Klinsmann has been paying attention for a while. In October 2014, the U.S. coach made Ibarra the first player since 2005 to receive an invitation to a national team camp while playing in the American lower divisions. U.S. fans’ knowledge of Yank prospects has become so extensive that chatter at American Outlaw watch parties can revolve around whether an 18-year-old in the second division of Finland (the Ykkönen, but you knew that) is ready for a call-up. And yet hardly anyone had heard of this 25-year-old midfielder from Lancaster, California.

A raw talent coming out of Lancaster High School, Ibarra didn’t receive a single scholarship offer from a Division I school and ended up at Taft College, just outside Bakersfield. He was a junior college All-American there in 2009 and transferred to UC Irvine for the following season. After his senior year at UCI, Ibarra was voted co-offensive player of the year in the Big West Conference, yet he went unselected at the 2012 MLS SuperDraft. The Portland Timbers picked him up in that year’s Supplemental Draft but let him go on the last day of training before the season. That’s when former U.S. international Manny Lagos, head coach of Minnesota United FC (then Minnesota Stars FC), brought him in and gave him a chance.

When Miguel came to Minnesota, it was quite obvious to everyone that he had something special under the hood — Lagos calls it his “tireless engine.” The coach saw that his new midfielder could recover almost instantly from a sprint to protect his fullbacks as well as spark counterattacks.

During his time with United, Miguel the man — “Migue” (Mee-gay) as some of his teammates call him — stayed under the radar, while Ibarra the player — speedy, skillful, hardworking — came to national attention. Ibarra earned his first call-up for Landon Donovan’s USMNT testimonial match, and the inclusion of a lower-division player caught everyone by surprise. Even Ibarra’s parents didn’t believe him when he phoned to tell them he had been summoned to his first national team camp. When it finally made the news, they called to congratulate him. “I already told you that!” he said.

In the months after his first USMNT call-up, Ibarra was used as a stand-in for the many American soccer debates: Don Garber vs. Jurgen Klinsmann, MLS vs. NASL, promotion/relegation, the role of college soccer programs, MLS’s roster rules, and, now that he has transferred to Mexico’s Club León, staying home vs. going abroad. No matter the issue, Ibarra could somehow be produced as evidence for one side or the other.

Just after the start of the 2015 NASL season, I meet Ibarra and his roommate/strike partner, Christian Ramirez, at Bryant-Lake Bowl in the Uptown neighborhood of Minneapolis. I have no idea if either of them likes to bowl, but Minneapolis celebrities like Josh Hartnett and Vincent Kartheiser (Pete Campbell from Mad Men) frequent the lanes here. Perhaps one of them will make a cameo in this profile. We need something to happen, because Ibarra is shy.

“We went to a new barber in Florida, and Miguel had me go first so that I would try it. I went, and I looked in the mirror and thought, ‘This isn’t turning out too good.’ But then Miguel gets up and says, ‘I just want the same as him.’”

Alas, Hartnett and Kartheiser are no-shows. (Ditto for Prince and Paul Westerberg.) Even worse, it’s league night, so we won’t be able to get a lane for three hours. Ibarra and Ramirez are apparently so hesitant about my plan to take them bowling that they have enlisted Eric Durkee, the team’s director of public relations, to come along. The four of us end up sitting around a small table in the dining room adjacent to the lanes. Durkee and I sip bourbon, while Ibarra and Ramirez take down glasses of water with their comically large plate of nachos. Ramirez pulls a solitary chip with sour cream from the pile, which is equidistant between the two, and puts it on a small plate before Ibarra — a gesture that says “the rest are mine.”

Ibarra laughs. “Everybody is always saying, ‘Every time we’re with you guys, you two are arguing,’” he says.

“They don’t understand how we can live with each other,” Christian says. “We went to a new barber in Florida, and Miguel had me go first so that I would try it. I went, and I looked in the mirror and thought, ‘This isn’t turning out too good.’ But then Miguel gets up and says, ‘I just want the same as him.’”

The two met when Ramirez trained briefly with Minnesota at the end of the 2012 season. Ramirez would eventually catch on with the Charlotte Eagles, but after one season there, and just days before he was going to sign with Sacramento Republic FC, he made the move to Minnesota — thanks to Ibarra convincing Lagos to pull the trigger on the acquisition. Since then, the two attackers have been inseparable.

And they both produced breakout seasons in 2014. Ibarra won the NASL Golden Ball with eight goals and four assists, while Ramirez took the Golden Boot with 20 goals. It is a partnership that led Bruce McGuire, co-host of the Minneapolis-based du Nord Futbol Show podcast, to dub the two of them Batman (Ibarra) and Superman (Ramirez). (Disclosure: I am the other co-host.) The nicknames stuck, and the players have occasionally worn Batman and Superman T-shirts underneath their jerseys.

Talk to Ibarra’s former and current coaches, and a picture starts to emerge — of a kid loaded with talent but shy, hanging at the back of the group. Even Ibarra seems to conceive of himself this way, stopping at one point to correct himself: “I’m 25. I’m no longer a kid.” When he was a kid, though, his raw talent is what Angelo Cutrona noticed about him right away. Cutrona, the head coach at Taft College, was watching a game between the Lancaster Rattlers (then a USL-PDL team, now the NPSL’s FC Santa Clarita) and UC Irvine. Ibarra was still in high school, but his play — and manner of running with his shoulders tucked over, like Cuauhtémoc Blanco — caught the college coach’s attention.

“Who’s that little kid who’s hunched over?” Cutrona remembers asking. “First touch on the ball, the kid’s amazing, beats two guys. All of a sudden, he doesn’t hesitate and just lets it rip from about 30 yards out. I thought, ‘This kid’s pretty good.’”

But he slipped through the college recruiting cracks, and Cutrona, surprised to find him available, tried to get him to come to Taft. Ibarra’s plan was to try to go professional right away, and he had a flight booked for Chicago, where he had a trial lined up with the Fire. But the night before he was supposed to leave, he heeded Cutrona’s pleas and signed up for Taft.

Cutrona says Ibarra needed a kick in the ass back then, that he “ripped him up pretty good.” When I quote this back to Ibarra, he knows exactly what I’m talking about.

“It changed everything,” he says.

Cutrona didn’t specify what ailed Ibarra, saying only that “he was being pulled away by outside distractions.” After practice one day, he told Ibarra, “Fuck your ability. What’s the point of having all this talent if you’re not going to use it?”

“You think you could have gone pro in Chicago?” Ibarra remembers Cutrona saying. “At this rate you won’t even start for me. You’re terrible. I don’t even want you here.”

Ibarra was dejected. He went back to his room, packed his bags, and called his father to come pick him up. But his father refused, and a friend came to his room and unpacked his bags. The midfielder ended up staying at Taft, trying to work his way off the bench. During a scoreless game against Fresno, he came on as a substitute and gashed his forehead. The trainer wrapped him up and he stayed in the game, eventually scoring the game-winner in the 90th minute.

Cutrona accompanied Ibarra to the hospital that night, which is where, he says, “Miguel learned I gave a damn.”

How did Ibarra end up in the second division if he was good enough to play for the USMNT? And how did he make it all the way to the international level when he was playing in the second division?

Ibarra says he is motivated by criticism like Cutrona’s that season. He stayed for the year before transferring to the much larger program at UC Irvine. But the lessons from Cutrona stayed with him. Ibarra recalls the end of the 2013 NASL spring season, when he came in for a lot of criticism from fans and the media. He had just listened to a season-recap episode of the du Nord podcast in which Bruce and I had roundly panned his performance, prompting him to send this tweet: “Alright I heard enough time to start proving people wrong. #MNUFC.” Ibarra finished 2013 as an NASL Best XI selection based solely on his performance during the fall season.

I remember that episode, but I didn’t know he had heard it. I gingerly tell him I’m one of the co-hosts.

“Yeah, well, I shut it off,” he says.

Ibarra followed the Best XI selection by winning the Golden Ball in 2014, earning three more national team call-ups in 2015, and, this past June, making a seven-figure transfer to Club León in Mexico’s Liga MX. The process has been affirming for fans of NASL teams who feel that the clubs and players they support are too easily dismissed by MLS fans and Eurosnobs. And for Minnesota United’s brass, Ibarra became a symbol of legitimacy. Owner Dr. Bill McGuire and president Nick Rogers had long talked about building a top-level team regardless of the league it played in, and here was a player who proved they were on the right track (even though Ibarra had been signed before McGuire took over the team). He was moving on, but his transfer provided a significant windfall for the up-and-coming club.

The week Ibarra sealed his transfer to León, he was in Germany with the U.S. national team. While he sat on the bench watching the U.S. upset the reigning world champs 2–1, Klinsmann’s provisional roster for the 2015 Gold Cup was announced — with Ibarra’s name left off — and rumors started to fly about his potential transfer to Mexico.

Ibarra knew there had been talks with Chivas de Guadalajara, but those had stalled. The rumored León transfer took him by surprise. He came back to the locker room to find his inbox full of messages about the move. “I didn’t know what was happening,” he recalls, “because I couldn’t use my phone.” He asked his roommate, William Yarbrough, who plays in goal for León, if the rumors were true. Yarbrough suggested Ibarra call his agent.

Later, when he spoke with Lagos, the coach was supportive, telling him it would be a big move. Ibarra had imagined himself in Minnesota, moving with the club to MLS, and working toward winning the MLS Cup.

“All of a sudden, though, you see this pop out of nowhere and it’s kind of surreal,” Ibarra says.

He put on a beat from Eminem’s 8 Mile soundtrack and launched into a freestyle rap about his teammates. Included in his rhymes was a joke about goalkeeper Brad Guzan looking like a polar bear. I thought, “Man, this guy is gonna kill me.”

Everyone else seemed to see it coming. Surely, a player who wants to be on the national team, the thinking went, needs to play for a bigger club than the second-division Minnesota United. During all of Ibarra’s U.S. camps, the question came up. Ibarra had obviously been practicing his response to it, because when I asked, he recited the same line I’d read in almost every story about him: “I decided to take this opportunity in Minnesota, and it has worked out for me. I have always been a hard worker, and the opportunity presented itself.” And now that opportunity has led to a much bigger one.

Ibarra says not much has changed for him in the national team picture since his transfer to León. Klinsmann spoke to him about why he was left off the Gold Cup roster. Ibarra told him that he believed it would be good to spend time in preseason with his new club and fight for a spot. He says Klinsmann never pressured him to move from Minnesota. The national team manager continues to say that if Ibarra plays well for his club, he can push his way back into the national picture.

The gulf between the NASL and the national team still puzzles American soccer fans. How did Ibarra end up in the second division if he was good enough to play for the USMNT? And how did he make it all the way to the international level when he was playing in the second division? I ask Ibarra what it was like to suddenly be running around the same pitch as Clint Dempsey and Jozy Altidore. He tells me that all of the players went out of their way to make him feel comfortable when he was first called in for two matches in October 2014. In the locker room it didn’t matter what league he had come from — Dempsey, Altidore, and Klinsmann all told him that he had worked hard for this and he deserved to be there.

There was also an initiation process: “I was so shy, and I wouldn’t speak to anyone, but they told me that I would have to speak in front of everybody.” He was supposed to memorize a song but couldn’t think of one. Instead, he put on a beat from Eminem’s 8 Mile soundtrack and launched into a freestyle rap about his teammates. Included in his rhymes was a joke about goalkeeper Brad Guzan looking like a polar bear. I thought, “Man, this guy is gonna kill me,” Ibarra recalls. The ice-breaking exercise was successful — though, sadly, Ibarra’s rhymes were neither written down nor recorded for posterity.

After Ibarra got his first cap in a three-minute run-out against Honduras in October, Klinsmann put his arm around the winger and said, “You’re a national team player now.”

As we talk over drinks and nachos, I endure a nagging disappointment that I haven’t contrived a situation for Ibarra and Ramirez to show off the competitive streak for which they’re famous. They had walked into the bowling alley saying they were betting a pair of cleats on the night’s games, but we haven’t thrown a single ball.

Thankfully, there are a few members of the Minnesota United supporters group, the Dark Clouds, bowling in the league competition, and they are more than happy to let their team’s stars join in for a few frames. Things heat up immediately.

“He picked the lightest one,” Ramirez says of Ibarra’s ball selection. And when they can’t decide who will toss first, they play rock-paper-scissors. Ibarra doesn’t try to hide his disappointment when Ramirez covers his rock with paper.

I had entertained visions of showing them up with my mediocre skills — of bowling a 150 as they begged for bumpers. Durkee laughs. “They’re professional athletes,” he says. “They don’t do anything poorly.” Ibarra steps up and takes a straight approach: strike. The Dark Clouds cheer. He struts back to the group. Christian follows with a perfectly curled attempt that hits the sweet spot: strike. More cheers.

The next frame goes poorly for Ibarra, and as Ramirez prepares for his own turn, Ibarra stands right next to his approach route. They argue over whether this constitutes cheating. Ramirez shakes off the distraction and bowls another strike, celebrating wildly when the pins fall. There’s some trash talk, all of it friendly, but you can see that Batman really hates losing, especially to Superman.

For all the appearance of upward mobility in Ibarra’s transfer to Liga MX, he says his family and friends gave him mixed advice on the move. These decisions aren’t just about the clichés of glory and “pushing your boundaries.” The player had been through it before, ahead of the 2014 season, when MLS clubs showed interest. Then, his father, Angel, had told him that the difference between MLS and the NASL didn’t matter to him. He wanted Miguel to find a place where he would feel comfortable and respected. Miguel felt both in Minnesota.

Ramirez’s advice in 2014 was, “Sometimes there is an offer you just can’t refuse. I think we both come from an upbringing where everything hasn’t been given to us. It’s never mattered what league you’re in or who you’re playing for or how much you’re getting, but if you’re respected and people see the hard work that you’re putting in, then that’s all that matters.”

And they both talk about coming from working-class immigrant families; Angel was born in Guadalajara (though he supports Club América) and works construction, and Ramirez’s father works in a military parts factory. Both sons say they are proud to be able to play soccer for a living while providing for their families. Neither took the opportunity for long-term security and stability in Minnesota for granted. But when it came to the León move, Ramirez told Ibarra that he had to take the opportunity. Lagos — who had tried to keep everything quiet until it was certain, to avoid distracting Ibarra during the U.S. camp — was of the same mindset. The deal was good for the club, good for the player, and now the question was, How could Ibarra grow as a person and on the field?

“I told him to come out of his shell early,” Ramirez said of his advice to Ibarra. Lagos echoed that: take all your hard work for the Loons and the U.S. and apply it, from day one, in Mexico.

That’s been a theme throughout Ibarra’s career — from Taft to UCI to the NASL to the USMNT. Each stop gave him the feeling that his hard work was being recognized and rewarded. I asked all of his coaches if they felt like he had “national team potential,” but none of them seemed to acknowledge this as a real category. For them, it is up to a player to discover his own ceiling.

Lagos sees Ibarra as a lesson to American soccer fans and media. “Development in soccer is not black-and-white,” he says. He bristles at the idea that he discovered a diamond in the rough or that the Portland Timbers were blind to Ibarra’s talent when they let him go. He says, “Miguel’s maturation coincided with our club maturing, me as a coach maturing. When people talk about his younger days, those are all just building blocks for him to succeed later.”

Cutrona agrees, saying, “I preach consistently about a process, a pathway. Miguel was potential. I knew he was one of the best players in the state. You never know what he’s gonna do down the road.”

I ask Ibarra how he responded when Blatter asked for him by name and called him the American Messi.

“At first, I didn’t even know he was going to ask for me,” he says. “I was kind of in shock.”

He tells the story with his usual shyness, laughing to deflect the attention. Ibarra is a confident player, but he is hardly comfortable hearing such a comparison. It’s for others to believe or to roll their eyes at. Ibarra’s content to unpack his bags at León, drop his head between his shoulders, and keep running.

Wes Burdine is a writer and a producer of Howler’s podcasts. Follow him on Twitter @MnNiceFC.