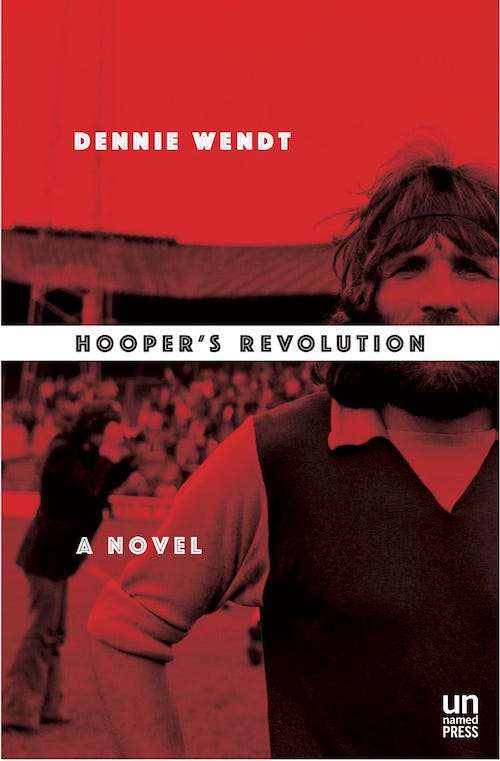

A re-imagining of American soccer’s origin story…with spies

Hooper’s Revolution is the excellent new book from Howler contributor Dennie Wendt. It’s set in a brilliantly constructed alternate world of 1970s American soccer and tasks its brutish English third-division footballer protagonist with foiling a communist plot. Pick up a copy from Amazon and get stuck in.

Here’s Dennie on the foundations of his unique tale and a few examples of the delightful world he created for it:

How a book happened

American soccer didn’t begin in the ’70s, but it may as well have. My sports youth, like many of my age and inclination, was pretty much Steelers-Cowboys, Dr. J and Bill Walton, Muhammad Ali…and the North American Soccer League. I was a sports-obsessed kid, so it all seeped into my pores and never really left. To this day, I know as much about the 1970s Portland Timbers as I know about just about anything else — that’s not good, it’s just true — so I finally decided to turn my habit of telling long, esoteric stories into a novel inspired by the weird and colorful world of the original NASL’s desperate effort to launch soccer into the American sports mainstream.

Playing on the road in the NASL was like navigating the PGA tour: players had to adapt their games to that day’s terrain. Portland had threadbare artificial turf and muddy sliding pits; San Jose had a ridiculously narrow natural-grass, small-college football field; numerous teams played on exposed baseball diamonds, while teams in domes toiled on hard turf moonscapes. I remember a recently imported Timber being called for a foul throw in Vancouver because he threw the ball in from one of the Canadian football lines on a confusing pitch that looked like the innards of a radio. A few teams played on overgrown, crazily-crowned high-school fields. It wasn’t until Oregon public TV started showing English and German games that I even knew that these players were accustomed to pitches of certain recognizable sizes and shapes. By then, I was old enough to be playing semi-seriously and to appreciate how remarkable it was that those immigrants from European and Latin American football managed to play as well as they did on those surfaces, in front of all those empty seats, with PA announcers explaining what a goal kick was. And then, in the early ’80s — which was still pretty much the ’70s if you ask me — it was all over, like a vivid fever dream that seemed real enough to go on forever but never really had a chance.

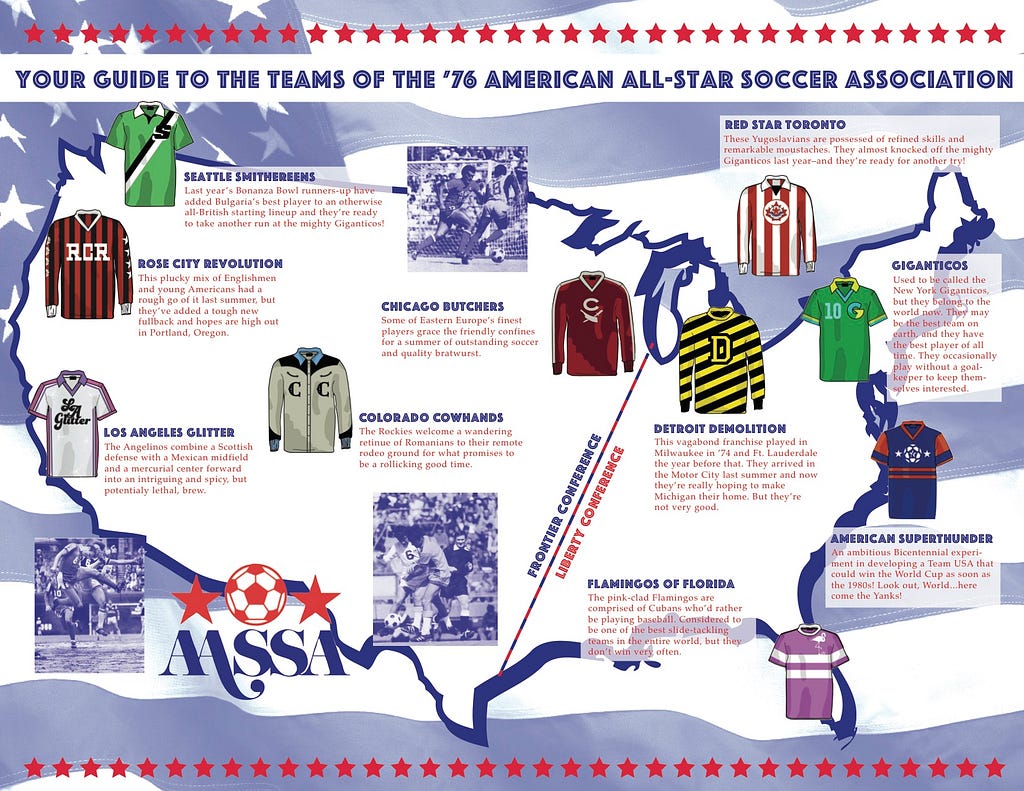

It was also a great time for conspiracy movies, actual conspiracies and Cold War intrigue. So I threw all that in a pot and came up with Hooper’s Revolution — a ’70s soccer adventure featuring an Englishman, a magical Brazilian, scary Russian secret agents with a sinister plan, and a team from the Pacific Northwest desperate to win a championship. The book is an alternate history of an NASL-like league, filled with vacationing English teams wearing American uniforms, Eastern Europeans navigating the Free World for the first time, and aging superstars making a quick buck, with stops at small-town rodeo grounds, beloved ballparks and cavernous, lonely suburban domes.

In other words, it’s the American soccer origin story. Kind of.

The book features numerous anecdotes about the (fictional) teams, English and American, that populated the ’70s soccer landscape. Here are two of each:

WOLVES & WOLVES FOOTBALL CLUB

Wolves United and Wolfingstonesgreen-upon-Heath Wanderers merged in 1973 after United slipped into administration following a poorly funded and ill-conceived world tour during which they produced seven wins, against 34 defeats and 11 draws and four confirmed player deaths in 40 countries over 60 days. When they returned, bedraggled and traumatized, for a preseason friendly in Wolfingstonesgreen, they learned that Wanderers had lost three quarters of their squad to a traveling cult/circus that had absconded to the Isle of Wight. The merger initially seemed not only logical but amicable, but hit a snag when the new club’s combined management could not determined whether to adopt United’s colors of red and white or Wanderers’ white and red. In the event, United retroactively changed its colors to claret and sky blue, while Wanderers posthumously reverted to their founding strip of green and white hoops. The new club, Wolves & Wolves, wore a halved jersey striped on one side in green and white and on the other in maroon and blue, occasioning Parliament to hastily pass an emergency act requiring W&W to play in all white for matches televised in color in the name of public safety. One snowy night in 1989, the team loaded its effects onto a boat off the Dennispool docks and travelled to America, where they became the Minnesota Timberwolves of the National Basketball Association.

DIRE VALE UNITED FOOTBALL CLUB

As of the 1975–76 season, Dire Vale held the remarkable distinction of being the only known footballing organization on the planet to have finished 12th in every league competition they had ever entered. This had come to light all the way back in 1903, after the team finished 12th in the Mid-Maidenfoot Alliance Second Division, despite a unique playoff system in which the teams were re-seeded after each match and the contests were scored by judges based on footspeed and playing style. In time, the club’s management determined to build the squad based on a stated desire to finish in 12th each year without ever being suspected of throwing a match; United’s unique aims put them in the awkward position of paying exorbitant transfer fees for players of what the club deemed “exactly our kind of mediocrity.”

CHICAGO BUTCHERS

Unlike most American All-Star Soccer Association clubs, the Butchers were, in fact, an established team with a deep and complicated history, a football club and social organization formed by immigrants between the wars. They had variously been known as the Chicago Ukrainians, Polish-Ukrainians FK, Polish White Eagles, Pipefitters Local 521, the Chicago Americans (for a couple of years during the Red Scare of the 1950s), Polish-Ukrainians (again), before landing in the AASSA and finding themselves in need of a marketable, merchandisable moniker.

The most notable feature of the Butchers’ stadium hung just behind one of the goals, nestled right up against the crowded grandstand of maroon-clad Butcher rooters: A cow — a big one, skinned, and rotating on a spit. The Butchers had a butcher mascot, a man in a red and black flannel shirt and a white, blood-spattered smock who wielded a pair of matching, elongated butcher knives as he riled up the crowd. As the cow cooked over simmering coals and released a sticky, fleshy smell, the butcher tossed his knives high into the air and caught them with marvelous, juggling flourishes that gave the crowd to murmur and hum. It was a startling display — not the kind of thing that filled you with the belief that you were just going to fight your way back into a match; it was the kind of thing that seeded in your subconscious the idea that you might not run out of the stadium intact at all.

The Butchers were part of a curious side story during that 1976 season, after two of their finest players finished off a late night of Chicago drinking by boarding an Amtrak instead of an El and would up in the small Idaho panhandle town of Sandpoint, where they were rescued/taken in by the local high school’s Spanish teacher, a Paraguayan who hoped to form one of the state’s first high-school soccer teams from a handful of basketball players and members of the track team. The Paraguayan promised the Poles he would finance their way back to Chicago if they would coach his players for a couple days in a clearing in the woods, outside of the townspeople’s prying eyes. He asked his high-schoolers to tell their families they were going for a long run, but Sandpoint’s football coaches got suspicious, tracked the clandestine company and broke up the secret soccer cabal by firing over their heads (but not by much) from their own duck blinds.

Sandpoint’s police determined not to press charges because the gunfire had been provoked by “severe maltreatment of basketballs, an important symbol of America,” and because no one had actually gotten shot. “You just can’t kick basketballs,” Sandpoint’s mayor said in the town’s first-ever press conference. In the event, the players were sent back to Chicago at taxpayer expense and the Paraguayan went with them, finishing the summer a Butcher.

COLORADO COWHANDS

It took less than a year for the AASSA’s Colorado franchise to vacate the Mile High City. The following summer, it relocated to the former frontier town of North Beef, enticed by local boosters who had plied the Cowhands’ ownership with a summer of free dates at the town’s rodeo arena and a set of 30 leather-fringed light blue Western shirts with pearlized buttons and the team’s logo — a cowboy lassoing a soccer ball — embroidered on the front, for uniforms.

When visiting teams arrived in North Beef, a little over an hour’s drive from Denver, their bus would pull into the 7–11 parking lot to be met by the mayor, a gaggle of civic-minded locals, and what appeared to be the Colorado Cowhands, looking a little ashamed of themselves — and vaguely Romanian, which they turned out to be (mostly) — in satin jackets and pants bejeweled in a manner befitting country music superstars. A band would be there too: The North Beef High School Marchin’ Varmints, along with a small squad of rodeo clowns goofing around with soccer balls in the parking lot while the band finally settled into its riff on “I Want to Hold Your Hand” in acknowledgment of the coach-full of Englishmen that had just arrived.

A representative from the club would usually meet the visitors at the parking lot for a brief run-down of the ground rules at the North Beef Stampede Days Arena, which included the news that there was only space for a seven-on-seven game, and that the players would be entering the playing area through the bucking chutes.

Hooper’s Revolution