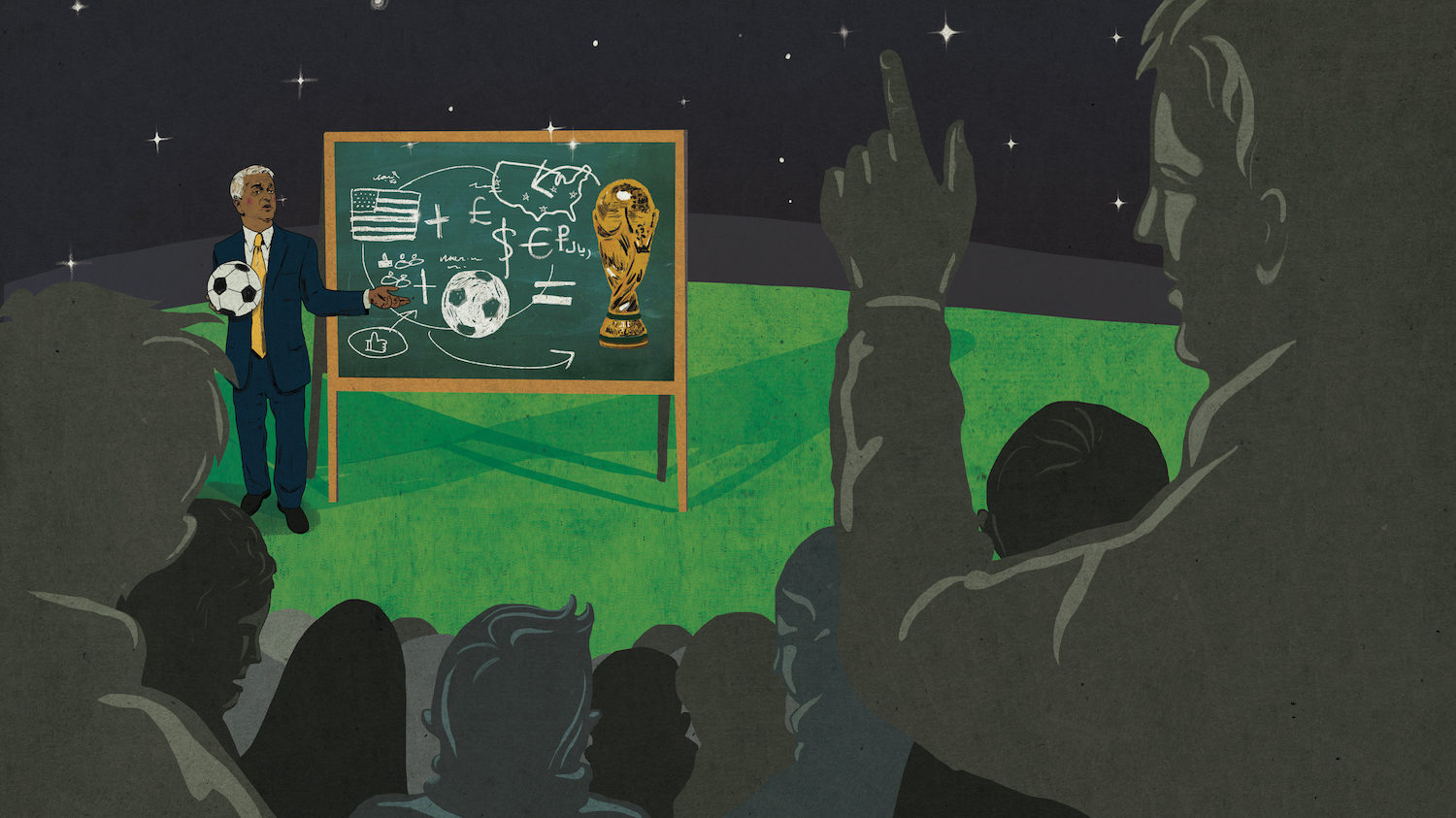

When he isn’t teaching economics to college students, Sunil Gulati moonlights as the most powerful American in world soccer. Will landing the 2026 World Cup vindicate the U.S. Soccer Federation’s long-term strategy of working within FIFA’s rotten system?

Illustrations by Barry Falls

Editor’s note: This feature appears in the Fall 2017 issue of Howler. Subscribe here.

Sunil Gulati was about to realize what is, short of flying, perhaps humankind’s most universally shared fantasy: He was going to play soccer with Diego Maradona. This was in January, and the 57-year-old president of the United States Soccer Federation and member of FIFA’s executive committee was preparing to travel to Zurich to take part in a boondoggle exhibition match with the FIFA Legends program. He and the other suits who run world soccer would team with the former Argentine superstar, Gabriel Batistuta, Carles Puyol, and others for a kickabout. There was just one problem: Gulati didn’t have any boots.

These days, Gulati spends most of his time in lecture halls, boardrooms, and the business-class sections of airplanes, not on the pitch. It had been a while since he kicked a ball outside of his kids’ practices and more than two decades since he last bought a pair of studs. He tried to get out of the match, asking if his 19-year-old son, Emilio, could play instead, but the game was limited to legends and council members. So: cleats.

The grounds crew said the turf field would be covered in snow. Gulati, concerned about traction and not wanting to make a fool of himself, needed some advice. He dialed up U.S. men’s national team head coach Bruce Arena. Then he got a second opinion from U.S. U-20 manager and American youth technical director Tab Ramos. He wanted to know if he should get molded boots or ones with studs. They both suggested the former. “I thought that was kind of cool, to call the national team coach to find out what shoes I should wear,” he told me over the phone in one of the many conversations we had across the eight months I spent reporting this story. When I began, Jurgen Klinsmann was still coaching the U.S. national team, and the American women were reeling from their early Olympics exit. We communicated often enough that Gulati jokingly asked if I was writing a profile or a book.

But back to the shoes. Taking Arena and Ramos’s advice, Gulati traveled the 20 blocks from his office to the Upper 90 shop in Manhattan’s Upper West Side and bought a new pair. “It was always going to be Nike,” he says of the brand he purchased, which, conveniently, has a multimillion-dollar contract to supply the United States national teams. He flew to Switzerland and played, mixing into a squad that featured Vítor Baía in goal, Eric Abidal at the back, and the tandem of David Trezeguet and Carli Lloyd up top. They finished second in the four-team tournament. Maradona’s squad, stacked with Batistuta, Marcel Desailly, and FIFA president Gianni Infantino, won. “There was some creative scorekeeping going on, I would imagine,” Gulati admits.

Creative scorekeeping. By FIFA. You don’t say.

Sunil Gulati’s career hasn’t all been pickup soccer with celebrities. The first thing to understand about Gulati is that he has worked almost every job in American soccer as the game has grown in this country, and few of them qualify as glamorous. He drove buses during national team camps. He bought balls at Kmart. He put airline tickets on his personal credit card. He helped build Major League Soccer to the point that an early fantasy game was marketed with the tagline, “So you think you can do better than Sunil?” He attended the weddings of players who starred for the U.S. in the 1990s, and he keynoted their Hall of Fame inductions. He’s been everything from ball boy and jersey procurer to deputy commissioner of MLS and president of the federation, and he helped turn U.S. Soccer into an organization with a $100 million budget and 140 full-time employees. Others, like Werner Fricker and Alan Rothenberg, played a larger role in early developments, but at this moment, no one else can claim to have been the driving force behind more important decisions than Gulati. And it’s not particularly close.

The other thing to understand about Gulati is that he didn’t arrive at the top by accident. “He has never been shy about affirming the fact that he has always wanted to have a powerful position in the field of soccer,” says Doug Logan, the first commissioner of MLS, for whom Gulati served as deputy. “And he’s very driven. I’m not at all surprised that he’s gotten to where he’s gotten.” Mix ambition and opportunity with ability and vision and you find yourself on a field with possibly the greatest player of all time and then meeting with the FIFA president you helped elect.

Soccer has been good to Gulati, and judging by the balance sheets of U.S. Soccer, he has been good for the game here, too. Ever the consummate politician and cautious economist, he has worked within CONCACAF and FIFA, trying to excise the rotten cores of those organizations from the inside. To hear him tell it, this was the only way, and the slate of current and continuing reforms in FIFA and beyond justify the decision. Critics of FIFA would point out that its crisis of conscience came about not by internal processes but thanks to intervention by the U.S. government. In any case, it is now clear that working at a high level in the arena of international soccer requires one to associate with a host of crooked characters. To have survived the downfall of so many is a remarkable feat; to have emerged even more powerful within FIFA is testament to Gulati’s considerable political skill. In the realpolitik of international soccer, it may not be fair or useful to measure Gulati by whether FIFA ever gets its act together but rather by whether he is able to realize his ultimate goal, the administrator’s version of results on the field: another World Cup on American soil.

Ask the parents of the players on seven-year-old Sunil Gulati’s soccer team which of the players had the brightest future in the sport and most would have pointed to Joe and Billy Morrone. Then again, this was in 1967; nobody in Storrs, Connecticut, had a bright future in soccer. Gulati had been living in the U.S. for two years at the time, arriving with his mother and sister from Allahabad, India, to join his father, who was earning a PhD in mathematics. Soccer was popular in the town, which is the home of the University of Connecticut. When the family moved about an hour down I-84 to Cheshire, he kept playing. Gulati took to the administrative side of the game as well, starting to coach five- and six-year-olds when he was 12 and organizing the travel team he played on when he was 16. The highlight of his playing career came in the U-18 state final, where his team fell to a Mansfield side led by two local legends in the making by the name of Morrone.

He played junior varsity at Bucknell University, moving from forward to sweeper. “I wasn’t big, strong, or fast, so it was easier when you play with a sweeper,” he told me during an interview in his Columbia office, a comfortable space crammed with economics books, photos of his two children and wife, Marcela (who is from Mexico and of whom he says, “She has to root for the U.S.—she understands how important it is to me”), and so many framed jerseys that there’s no longer room on the walls. “Your vision, tactical awareness, positioning becomes more important than some physical characteristics.”

Gulati graduated in 1981 and began working for the Connecticut Olympic Development Program, then called the State Select Team Program. He met Chuck Blazer, who was running a similar program for eastern New York. Gulati thinks their squads probably played some games against each other. That is, decades before they were Chuck Blazer, CONCACAF giant and eventual pariah, and Sunil Gulati, USSF president and FIFA Executive Committee member, they were two dudes trying to get matches for their 16-year-olds. It’s easy to see how a friendship formed.

Some people joked that MLS stood for “More or Less Sunil.”

After demonstrating his abilities—and because no one else wanted to do so—Gulati ran a national team camp in Colorado Springs in 1985. Such was the state of organizational chaos, he had to buy balls at a nearby Kmart on a Sunday morning. He expressed his disgust to new USSF president Fricker, who told the young man to send him suggestions—but not a “17-page letter.” Gulati, being young, cheeky, and full of confidence, typed out a 17-page memo on his Macintosh. He says he no longer has a hard copy but thinks it’s on a five-and-a-half-inch floppy disk somewhere in his archives. Fricker liked the memo enough to hand Gulati various unpaid assignments, such as chairman of the International Games Committee. It was his first notable step on a 30-year climb to the top of American and then world soccer. It was also among the first of many titles Gulati would assume for the federation that were important but thankless, the type of gig that’s perfect for an ambitious young executive on his way to somewhere else. Gulati helped the U.S. win the ’94 World Cup bid, working closely with Blazer, among others. He did whatever was needed, like on a youth national team trip to Honduras in 1987, when what was needed was a math tutor for the players. After stints teaching at Columbia and then working for the World Bank, where he was Moldova’s country economist, he took a role as executive vice president and chief international officer for the 1994 World Cup.

Gulati thought he’d spend two years working on the organizing committee and then return to the World Bank, but instead the 36-year-old joined Major League Soccer as deputy commissioner in 1995. He put his economist’s training to work as an architect of the league’s single-entity structure. He also recruited players, serving as a soccer expert for commissioner Doug Logan, whose experience was in the sports entertainment industry. Gulati drew praise for his ability to navigate the complex, stressed financial system of MLS, which some people joked stood for “More or Less Sunil.”

Then things seemed to go wrong. He lost an election for USSF vice president in 1998. The next year, Gulati was fired from his job with the league after a falling-out with Logan, reportedly sparked by his decision to unilaterally re-up Tab Ramos’s contract without consulting the commissioner or New York/New Jersey MetroStars operator-investor Stuart Subotnick. At a press conference announcing the news, Logan offered a simple “no comment” about the decision to let his deputy go. (Don Garber replaced Logan three months later. According to Filip Bondy’s book Chasing the Game, Gulati was interested in returning to his job but he “had antagonized too many people.”) Instead he consulted with AIG and the FIFA World Cup Ticketing Bureau while working part-time with Kraft Sports Group, owner of the New England Revolution. He served on the board of directors for the Women’s World Cup in 1999 and 2003, joined the USSF as executive vice president in 2000, and returned to Columbia as a lecturer in 2003.

In 2006, Gulati ran unopposed for USSF president, replacing nephrologist Robert Contiguglia. He joined the CONCACAF Executive Committee a year later while also becoming a member of the FIFA Strategic Committee and the FIFA Confederations Cup Committee. In 2013, Gulati took a spot on FIFA’s executive committee, replacing Blazer, who did not run for reelection amid a scandal that would see him plead guilty to corruption charges in 2015.

These are just the top-line bullet points. They leave out the formal and informal relationships he made along the way, the loyalty he showed and earned, the little things he did, like the time in 1995 when he flew with Alexi Lalas from his club in Italy to a U.S. national team game, simply to accompany the defender on the long journey.

Gulati’s résumé is strong, but it’s the decades of small gestures that really begin to add up. Like any politician, he knows the importance of handshaking and baby kissing. Steve Jolley, a former MLS defender, remembers winning the MLS Humanitarian of the Year Award in 2002. At the ceremony, Gulati spoke to him for half an hour about how it would be the high point of the player’s career. “It meant a lot for a guy like Sunil to understand the significance,” Jolley said. “He reiterated the importance that there are bigger things than playing soccer. It meant the world to me.”

Mark Semioli, the 44th pick in the inaugural MLS draft, has a similar story. “He’s given me his number,” he said. “I called him or texted a couple times, and he’s gotten back to me within like three seconds. If he’s getting back to Mark Semioli in three seconds, he’s getting back to everybody quickly. I’m not close to him, but if I ever wanted to reach out about something soccer-related, he would connect me or do something for me. And I would do the same for him. I don’t know what I would do for him, but I would.”

We were walking across the quad to Gulati’s intro economics lecture, where he was about to teach roughly 200 students. He seemed to know a lot of people on campus, exchanging a dozen hellos on the five-minute trek from his office to class. It was the day after the first presidential debate, and he had been up late the previous night watching Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump exchange barbs, while also keeping an eye on the elections for the Asian Football Confederation because Moya Dodd, a friend of his, was running for a seat on FIFA’s executive council. But the elections were postponed, waylaid by controversy and politicking. As a result, the AFC would have only two representatives at the upcoming FIFA meeting instead of the five it is allotted. “Nice way to shoot themselves in the foot,” he said as we walked across campus, a brief flash of the unscripted Gulati that emerges from time to time.

At 9:30 a.m. on Tuesday, Gulati had already taught one class, a makeup of one he missed the previous week because of his unceasing travel schedule. The school year requires creative balancing. After class, he was heading to a CONCACAF meeting in Miami for the rest of the day before returning to teach on Thursday, then flying to Amman, Jordan, that night for the U-17 Women’s World Cup. “If I didn’t have to teach, I would be leaving Thursday morning from Miami to go to Amman,” he said. “The following week, we go to Cuba with the national team. I come back because I have to teach a class, and then I’ll go to Zurich the next day.” A bad trip is one where Gulati is in the air longer than he’s on the ground. He mentioned an overnight flight to Zurich and a 5:00 p.m. same-day return with the air of someone who has taken it many times. He flew between 250,000 and 300,000 miles in 2016 and has top-tier status on both American and United.

See him teach, however, and it’s clear why he flies back from the ends of the earth so as not to miss class: he clearly loves being center stage. Students like him, too. The Columbia Spectator has a series of early 2010s live blogs detailing how students would camp out the night before to sign up for his senior seminar. (They’ve since changed the rules so spots are awarded by online lottery.)

He delivered his lecture without notes, wearing a Frida Kahlo tie—“How many people think it’s Salma Hayek?”—working through a series of charts across six chalkboards. His energy would have surprised the many soccer reporters who are used to the laconic, heavy-lidded Gulati they usually encounter at soccer events. Here he pushed students to find the answers he already knew, and he wasn’t afraid to call someone out when necessary. He gently chided a student for speaking too quietly and did it again when the young man failed to raise his voice. Gulati controlled the room with a combination of everyday interactions and a few carefully timed flourishes. Early in the semester, he showed the class a receipt from Zurich’s Baur au Lac, the five-star hotel where the FIFA arrests took place last year. “That was a power move,” a student said, recounting the tale with awe in his voice.

Before the first assignment was due, another student told me, Gulati stipulated that all papers must be stapled. When the assignments came back, the professor held up one that wasn’t stapled. He asked the class to decide whether he should accept the paper anyway. The class voted that he should. He looked down to the assignment in his hands, back up at the class, and then dramatically ripped the paper in half. “This is not a democracy,” Gulati said. Only then did he reveal that instead of holding an actual student assignment, he had shredded a stack of blank pages.

{{Privy:Embed campaign=306930}}

“Leadership is about having a vision and trying to convince people of that vision,” he said in his office. “That doesn’t mean that you don’t make changes or talk to a lot of people as you’re developing that, but eventually you have to get people to buy into what you want to do and where you want to lead.”

“He’s never said, ‘Try to outwork me,’” said USSF secretary-general and CEO Dan Flynn. “He always says, ‘Try to outthink me.’ He says he wants to be challenged by our strategy, how we’re doing, and how we’re getting better. He wants to be challenged. He likes to be challenged. That keeps him engaged.”

Logan, the former MLS commissioner, had a slightly different take. “I don’t necessarily see him as a consensus builder. He has a very clear idea of where he wants to go and then gets people to follow that. That’s one effective way of leading. But I don’t know that he’s of the school of ‘everybody hold hands and all you people tell me what you want and we’ll make a stew out of that.’ He has a pretty good idea of what he wants before those conversations take place, and he is able to, in one form or another, get people to agree with him. Those that don’t agree with him don’t carry the day.”

Logan rarely talks about his relationship with Gulati in public even though he hasn’t seen his former deputy for years and no longer works in the soccer world. He only responded to my inquiries, he said, because of persistent e-mailing, and even then he declined to talk about the specifics of their relationship. I asked if he had any stories that he felt typified Gulati’s approach and attitude. “Many,” he said before pausing, laughing, and adding, “but I’m not going to tell you any of them.” To report on Gulati is to have many similar conversations, to hear vague critiques but few on-the-record anecdotes to back them up. If the man who fired him nearly 20 years ago won’t be critical, who will?

Gulati was busy working the room, the rest of us watching on TV. It was February 26, 2016; the first ballot to elect Sepp Blatter’s replacement as FIFA president had just been cast, and Gulati’s candidate lost. Fox Sports’ broadcast from the floor of a Zurich hockey arena entered a holding pattern as everyone tried to make sense of the results: 88 votes for Gianni Infantino, the Swiss Italian UEFA executive, to 85 for Bahrain’s Salman bin Ebrahim al-Khalifa. Jordan’s Prince Ali bin al-Hussein, the USSF’s preferred candidate, picked up only 27. Since there was no majority, a second round loomed.

The last time Gulati had put this much muscle into a FIFA vote, to select the 2018 and 2022 World Cup hosts, he lost. That was six years earlier, in December 2010. Russia and Qatar beat out the United States, which had been considered the overwhelming favorite to host the latter event. “I don’t think he was Pollyanna about FIFA or soccer in general, but when you get stung like that, it hits home even more,” said Alexi Lalas when I spoke with him for this story and who, on this day in 2016, was commenting on-air as the members prepared for the second ballot of the presidential vote.

While there is no direct through line from the World Cup vote in 2010, which was tainted by allegations of bribery, and the corruption charges that brought down a number of FIFA’s senior leaders, the decision to award the tournaments to Russia and Qatar played a role in altering the organization. The suspect circumstances drew international attention, and the USSF and the English FA, which lost out on hosting despite being the prevoting favorite, felt aggrieved. Over the next year, allegations of bribery continued to surface, with FIFA suspending Qatar’s Mohamed bin Hammam and Trinidad and Tobago’s

Jack Warner.

“In a way, that decision [on December 2, 2010] and the subsequent next few months, which involved the presidential election, led to consequences that changed FIFA forever,” Gulati said.

In 2011, Gulati and the USSF supported the reelection of Sepp Blatter in spite of the ongoing controversy. England tried to postpone the uncontested vote, citing Blatter’s lack of a “proper, credible mandate,” as English FA chairman David Bernstein put it. The measure failed, 172–17. Gulati says he isn’t sure how the U.S. voted because a member of the federation board cast the American vote, but he believes that the U.S. did not support the motion. Regardless, Blatter was reelected with 186 of the 203 ballots cast, including that of the United States. For Gulati, the choice was simple: Blatter didn’t have an opponent, so the U.S. could either vote for him or abstain, which Gulati viewed as an ineffective protest.

On April 19, 2013, Gulati joined the FIFA Executive Committee after defeating Mexico’s Justino Compeán, 18–17, for Blazer’s vacated seat. As corruption charges embroiled the organization—culminating with the Department of Justice raid of Baur au Lac in May 2015—Gulati remained untouched, consolidating a position that would make him a leader in the post-Blatter FIFA. “There’s an informal way of understanding how things need to get done that’s really important in world football,” Flynn said.

And as Lalas and his cohosts talked through the implications of the first round of voting, Gulati displayed his increasing power, working the room and urging his bloc to abandon Prince Ali al-Hussein in favor of Infantino for the second round. The camera showed Gulati holding court as Infantino and two other gentlemen leaned in, listening. His sudden visibility launched the Twitter hashtag #GulatiCam, which bounced around the American soccer community.

“I didn’t realize it was going to be quite as visible,” he said. “When I first knew, Alexi sent me a text. I was on the dais. He said, ‘You realize that we’re following you?’ I didn’t. But from my perspective, that’s the only way to get the result.”

He believes he had influence because the Americans had vocally supported Prince Ali twice, including the previous May, when the U.S. picked the Jordanian during his failed campaign against Blatter. “We had been outspoken in support where many others hadn’t been,” he said. “In this case, the fact that we were willing to support Gianni was useful for a number of people and helpful in terms of their own thinking, especially in terms of the people from CONCACAF.”

When the second round of voting came in, Infantino won by 27 votes over Sheikh Salman, the prevote favorite. For the first time, the U.S. had played a vital role in electing a FIFA president. Gulati was instrumental.

His influence extends beyond the voting arena. In his Columbia office, he spoke proudly about trying to bring more accountability to the organization. That includes instituting measures that are standard in American corporations or nonprofits, things like full transparency on compensation, transparency for bids on contracts, an independent ethics panel, term limits, and an independent governance committee. “What you need is good rules to give people the right incentives, and if they are outside of those rules, to make sure that you’ve got the tools to take action,” he said. “A lot of that has happened, but it’s going to take a long time.”

An admirable goal, but how much have he and his allies been able to accomplish by working within FIFA’s own system? The public still doesn’t know how much money FIFA executives make, including Gulati’s own compensation. Upon joining the executive committee, he said, “I would have no problem of disclosing if it’s not a violation of any provision with FIFA for directors.” In August 2016, FIFA released payment information for the president and general secretary for the first time, but Gulati’s pay remains a mystery. Gulati and six other executive committee members say they wanted to release the full 350-page report compiled by prosecutor Michael Garcia about the 2018 and 2022 World Cup vote,

but it was locked from public view until the German tabloid Bild forced FIFA’s hand in June. (Gulati stayed in touch with Garcia. During our interview in Gulati’s office, the two were e-mailing about the session of a Columbia law professor’s sports ethics class that they had been asked to co-teach.) FIFA is a little more transparent than it used to be, but it has a long way to go.

Furthermore, it’s fair to ask how many of the changes came as a result of internal actors versus outside pressure, such as the investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice, which resulted in charges being brought against 25 individuals. Gulati argues that internal reform was occurring, and the suspension of former power brokers like Blazer, Warner, Bin Hammam, and others from 2011 to 2013 indicates there’s some validity to that argument.

“A lot of things happened before the DOJ issues,” Gulati said. “What the outside pressure does is gives people on the inside the ability to find their voice, frankly. Because if you’re on the inside and you don’t have allies, trying to promote change is difficult and sometimes impossible.”

Would the FIFA reform process be as far along without those outside pressures?

“No, I don’t think there’s any doubt that some of the outside pressures have been instrumental in helping to push change through,” he said.

To his critics, it is incomprehensible that Gulati failed to notice the crimes being committed by Warner and Blazer during their years in charge of CONCACAF. There he was on the CONCACAF board, a Columbia economics professor, no less. Gulati has so far remained pretty much silent on crimes that were being committed at CONCACAF while he was involved with the organization. When the United States Senate held a hearing into international soccer governance, the fact that USSF CEO Dan Flynn appeared instead of Gulati caught the attention of investigative journalist Andrew Jennings, who opened his testimony by focusing on the “massive, massive deficiencies of the U.S. Soccer Federation, frightened to upset President Blatter’s corrupt FIFA while enjoying the elite lifestyle that he provides.”

“I note the absence of your FIFA delegate, Mr. Sunil Gulati,” Jennings continued. “That’s one crucial question today. Where’s Sunil? Where is he? He’s the man who takes American values, supposedly, to FIFA and to CONCACAF, and he’s not here to talk about it. It rather undermines the whole process, I think.”

Where was Gulati? Behind the scenes, as usual. Very possibly working to improve FIFA from within, as he claims. But the secrecy with which FIFA, and Gulati, go about their business makes this difficult to see from the outside.

“Gulati has not in any way positively affected that process,” said Chris Eaton, the integrity expert and adviser to the president of the International Centre for Sport Security, via Skype from his home in Lyon, France. “In fact, he has endorsed that process with the support of Infantino at the election. He tried to play the role of kingmaker.”

I wondered if Gulati would like to someday be king. When we were talking about the path he took to the top of U.S. Soccer, he mentioned that he didn’t think anyone who ran for vice president didn’t also think about being president. But when I asked a few minutes later if he wanted the top spot at FIFA, he demurred. “Might there be a FIFA president who is American in the next years? Sure,” he said. “But it’s not going to be me.”

There is still plenty to do in America. One of those things is helping the National Women’s Soccer League gain solid footing, and in February he sat at A+E Networks headquarters in Midtown Manhattan for an announcement that the cable company had taken an equity stake in the NWSL and would broadcast the games. During a flashy opening video, Gulati sat with a bemused look on his face next to A+E president and CEO Nancy Dubuc, pointing out to her the various soccer personalities in the room. When it was time for his remarks, Gulati took the microphone and made an opening joke right out of his econ lecture: “The ovation was louder for Nancy. But she pointed out that most of you in the back work for her, so it’s understandable, I guess.” Then he offered some quick thoughts about how the investment was yet another sign that the league was “here for the long term.”

“He’s been, in many respects, one of the strongest and at the forefront of trying to influence how impor-tant women’s football is, and not just from a World Cup and increasing prize money [perspective],” said Flynn. “That’s the obvious stuff. But literally getting countries to focus more on it.”

That’s true. Former Australian executive committee member Dodd called Gulati’s leadership in the women’s game “fantastic” in 2016, and he was a speaker at the 2016 FIFA Women’s Football and Leadership Conference. The U.S. invests more resources than any country into its women’s program, and he’s played a vocal role in encouraging other nations to increase their support of the women’s game.

And yet U.S. Soccer spent two years stuck in a contentious CBA negotiation with the U.S. women’s team. A deal was signed in April but only after both sides suffered significant PR hits. Megan Rapinoe thinks Gulati could be more of a force. “It’s quite frustrating to know that he’s making comments that he wants to get a deal done, but he hasn’t come to one meeting,” she told the New York Times last July. “I’ve been to three meetings, flown six hours across the country, and interrupted my rehab to come to New York, where he lives. And he can’t come to one meeting.”

{{Privy:Embed campaign=306930}}

Gulati, who did attend meetings later in the process, would say that he was a leader delegating responsibility. He can, after all, only be in one place, and there are many demands on his time. (As news of the CBA signing broke, he sent me four e-mails in 16 minutes answering a question about a wholly separate issue.) Others, however, have seen the hands-off approach before. “He’s trying to help now, but it’s like he gets pushed to a brink where he has to help. It’s a reaction rather than being proactive, and I wish he was more proactive,” former U.S. defender Cat Whitehill said. “He took a stand against the pay discrepancy, but I never really heard anything from him when Sepp Blatter insults the women’s game and tells people we should be wearing tight pants. I wish that I could hear more from that side of things.”

“More proactive” is the criticism that pops up most when people talk about Gulati. For an executive praised for his vision—former MLS commissioner Logan called him someone who “thinks so quickly that he normally can anticipate that next step”—Gulati does get into positions where his hand is forced or he seems to be dragging his feet. It happened with the U.S. men’s national team, where he stayed with Jurgen Klinsmann for too long, well beyond the point at which the team’s dysfunction was obvious from its performances on the field. (On this charge, he responded, “Whenever you’re dealing with personnel issues, patience is generally a good idea.”) His leadership in the women’s game could have been more forceful. He helped bring about new leadership at FIFA only to empower the same sort of characters who’ve been there all along. Before Infantino won the presidential election, he spent nearly two decades in UEFA as director of the Legal Affairs and Club Licensing Division, deputy general secretary, and general secretary.

“More proactive” is the criticism that pops up most when people talk about Gulati. For an executive praised for his vision—former MLS commissioner Logan called him someone who “thinks so quickly that he normally can anticipate that next step”—Gulati does get into positions where his hand is forced or he seems to be dragging his feet. It happened with the U.S. men’s national team, where he stayed with Jurgen Klinsmann for too long, well beyond the point at which the team’s dysfunction was obvious from its performances on the field. (On this charge, he responded, “Whenever you’re dealing with personnel issues, patience is generally a good idea.”) His leadership in the women’s game could have been more forceful. He helped bring about new leadership at FIFA only to empower the same sort of characters who’ve been there all along. Before Infantino won the presidential election, he spent nearly two decades in UEFA as director of the Legal Affairs and Club Licensing Division, deputy general secretary, and general secretary.

To some, this doesn’t go far enough. To Gulati, it’s about finding a balance. “When you’re talking about making comments about leadership at FIFA or anywhere else, U.S. Soccer is essentially conducting a foreign policy,” he said. “Often, I think, people don’t realize that. There are times when you have to be more diplomatic and times when you have to be less diplomatic if you want to achieve the right goals. If one is the outlier on every issue, you’re not going to get very far in those circles, or any circles, whether it’s a corporate boardroom or a political environment.”

This, in essence, is the idea that guides Gulati: that it’s better to pick your moments of dissent carefully—like supporting Prince Ali during the 2011 FIFA election—and to work to slowly remake the room than to try to blow it up and get booted doing so.

It’s impossible to deny the progress made under Gulati’s tenure, especially on a domestic level. Soccer in America has come along further and faster than pretty much any sport anywhere else in the world—but still not far enough, especially for the cohort that really started paying attention after the 1994 or 2002 World Cups.

“Fans have every right to say, ‘Don’t tell me you used to walk uphill to school both ways. What is it like now?’ and that’s fair,” Gulati said. But, he would argue, don’t forget the past. The USSF has gone from an organization that proposed taking away five-dollar per diems for players to afford an extra day of training during a camp in the 1980s and, according to Arena, was “on the verge of bankruptcy” in 1998 to one that has a $100 million budget that supports 17 national teams, a host of development academies, and a financial base that rivals the richest federations in the world. While the roots of this rise started before Gulati took over as president, his fingerprints are all over the blueprints from the past and the plans going forward. To use a metric an economics professor might appreciate, soccer in America has progressed 30 units in the last 30 years. But rather than going from zero to 30, it’s gone from -10 to 20.

His tenure isn’t over, but it’s coming toward a conclusion. He has, at most, one more term as USSF president and two in FIFA because of term limits he helped install. Gulati’s major final endeavor is bringing the World Cup back to the U.S. In April, he sat in the center of a podium on the 102nd floor at One World Trade Center, flanked by CONCACAF and Canadian Soccer Association president Victor Montagliani and Mexican federation head Decio de María. The trio announced a joint bid to host the 2026 tournament, with the U.S. getting 60 of the 80 games, the first among equals. Some pundits were not happy with the arrangement. “I think 10 games is an embarrassment,” wrote TV Azteca talking head Gerardo Velazquez on social media following the announcement. “It is something that only demonstrates the power Sunil Gulati has in the region and that the real giant in CONCACAF is the United States and not Mexico.”

His tenure isn’t over, but it’s coming toward a conclusion. He has, at most, one more term as USSF president and two in FIFA because of term limits he helped install. Gulati’s major final endeavor is bringing the World Cup back to the U.S. In April, he sat in the center of a podium on the 102nd floor at One World Trade Center, flanked by CONCACAF and Canadian Soccer Association president Victor Montagliani and Mexican federation head Decio de María. The trio announced a joint bid to host the 2026 tournament, with the U.S. getting 60 of the 80 games, the first among equals. Some pundits were not happy with the arrangement. “I think 10 games is an embarrassment,” wrote TV Azteca talking head Gerardo Velazquez on social media following the announcement. “It is something that only demonstrates the power Sunil Gulati has in the region and that the real giant in CONCACAF is the United States and not Mexico.”

Gulati shaking hands of the U.S. players before the final—if we’re going to dream, let’s dream big—would be the perfect cap on a long career that began in earnest when USSF officials convinced him to leave the World Bank in 1992 to help with preparations for the 1994 event. “Alan [Rothenberg] and Scott [LeTellier, the principal author of the 1994 bid] said, ‘Come do this for a couple of years. It’s the only World Cup we’re going to host in your lifetime,’” the economics professor said. “I hope they were wrong.”

By 2026, there will be a better sense of whether the reforms at FIFA succeeded or not. We’ll know if the qualities of patience and restraint, practiced by Gulati and scorned by FIFA’s many critics, have paid off. Right now, it’s possible to argue both cases.

The one sure thing in both scenarios: Sunil Gulati comes out on top.

Noah Davis writes about soccer (and other strange things) from his apartment in Brooklyn (and other strange locations).

Barry Falls is an illustrator who has worked for the New York Times, the Guardian, American Airlines, UNICEF, and Random House. He lives in Belfast, Northern Ireland, with his wife, two sons, baby daughter, and dog, Maisey.

Contributors

Noah Davis