Subcomandante Marcos and the Zapatista Theory of Fútbol

April 17, 2021

WORDS

George Sanchez-Tello

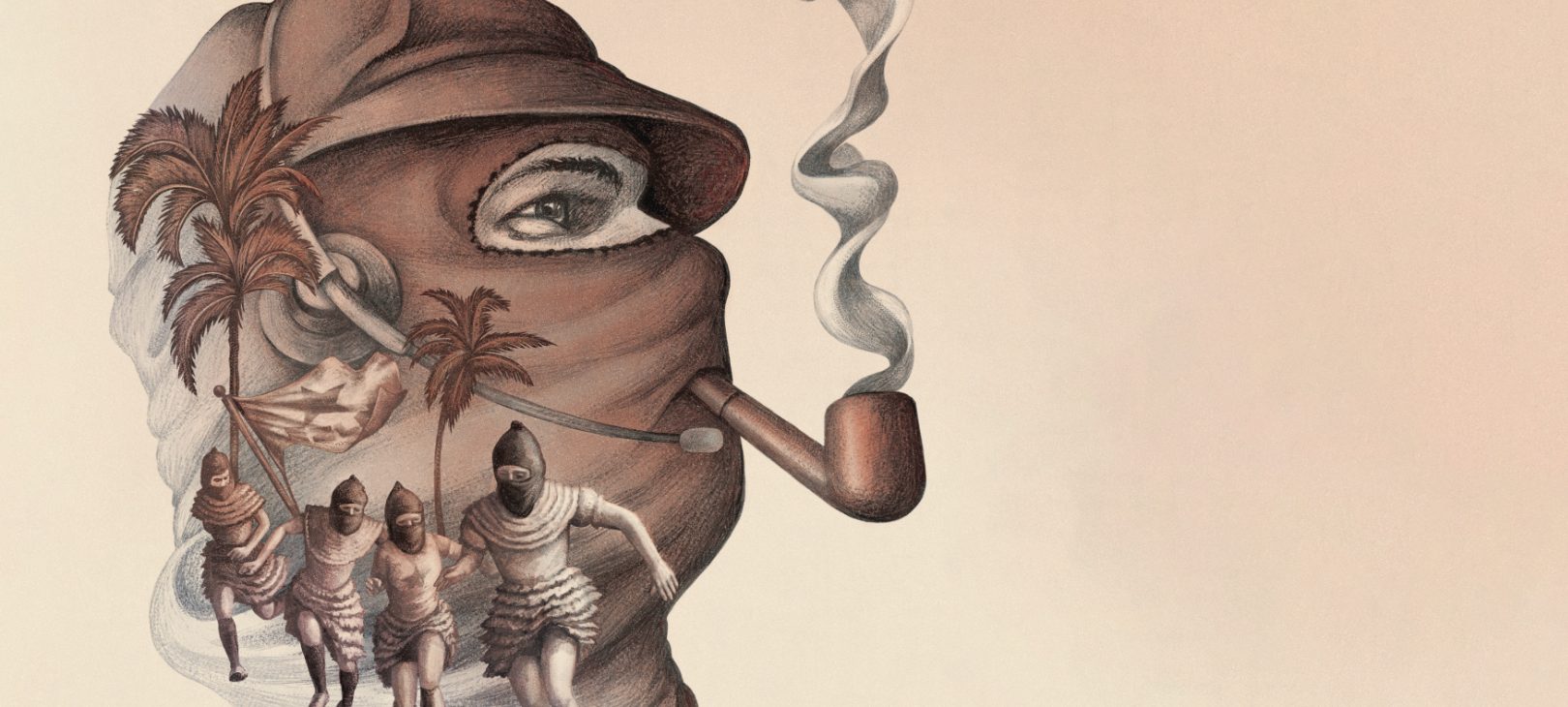

Illustration

Muti

Among the tools of the Zapatista National Liberation Army — indigenous wisdom, arms, organizing, international support and media savvy — is fútbol.

The setting is always the same: Mexican pastoral in wartime. There are usually children, often a ball. Mud roads up misty mountains. Cobblestone paves the town roads that lead into dense forest.

Campfires crowded with comales to cook tortillas and pots for coffee. Fire smoke mingles with tobacco smoke. Rifles are ubiquitous, leaning against centuries-old Ceiba trees. In hushed tones, languages spoken before the arrival of Spanish and English dance over the crackle of branches, the falling of rain and the call of a bird. Chiapas.

The writer is Subcomandante Insurgente Galeano. For many years before that, he was known as Subcomandante Marcos, or simply Marcos. Whatever the name, in the early 1990s he became, through his letters as well as public and media appearances, the eloquent voice and masked face of the Zapatista rebellion, which has reclaimed indigenous land from the Mexican government in the southern state of Chiapas. And he might have played professional soccer.

An international icon of leftist struggle and revolution, Marcos’s masked image is as pervasive as the famous profile of Che Guevara. Even Shepard Fairey’s Obama Hope image. The Zapatistas themselves took their name from the southern leader of the Mexican revolution—Emiliano Zapata, who famously fought for agrarian land reform under the slogan “tierra y libertad”—land and liberty. Marcos’s books are shelved today alongside Noam Chomsky, Frantz Fanon, Naomi Klein and Marx. Marcos and the Zapatistas vigorously interrogated globalization and the impact of global market forces on town squares—closed-door decisions that decimated the livelihoods of small businesses and subsistence farmers. From time to time a close friend asks about the Zapatista revolution. The land they took back is still theirs. The Mexican government still wages a campaign of harassment against the Zapatistas.

Among the tools of the Zapatista National Liberation Army—indigenous wisdom, arms, organizing, international support, and media savvy—is fútbol. The Zapatistas have fielded a squad in Mexico City. Their work has prompted Inter Milan to invest in Chiapas youth soccer.

As part of their outreach, they host solidarity groups, including Banksy’s Easton Cowboys and Cowgirls, who tour autonomous Zapatista zones and play against teams of Zapatista soldiers.

And then there are the many thousands of pages penned by Marcos, which provide perhaps the most accessible and yet underexamined clues about why this movement has consciously linked itself with the game of soccer. Here we find his exhortations to defy neoliberal policy and injustice at the hands of government. We find quixotic tales of an indigenous elder named Don Antonio and a talking, pipe-smoking beetle who goes by Nebuchadnezzar. And throughout them all, you find stories about daily life in the Lacandon Jungle and among the themes of hope, courage, tragedy, and humor, you find a constant stream of children and fútbol.

But I hesitate to read too much into Marcos and his writing. In May 2014, the enigmatic Mestizo who had been calling himself Marcos announced in a speech given in La Realidad in the middle of the night that Marcos would cease to exist. He said that he would now call himself Subcomandante Galeano, calling his identity an invention “a complex maneuver of distraction, a terrible and marvelous magic trick, a malicious move from the indigenous heart that we are, with indigenous wisdom, challenging one of the bastions of modernity: the media. And so began the construction of a character named ‘Marcos.’”

From the same speech, another warning: “If you will allow me one piece of advice: you should cultivate a bit of a sense of humor, not only for your own mental and physical health, but because without a sense of humor you’re not going to understand Zapatismo. And those who don’t understand, judge; and those who judge, condemn.”

Believing their struggle began centuries earlier, the armed insurgents struck on January 1, 1994, when 3,000 masked and armed indigenous rebels emerged from the Lacandon Jungle of Chiapas and occupied six towns and hundreds of ranches. Nearly 150 indigenous people were killed in response by a Mexican army wielding modern weapons. Demonstrations across Mexico demanded an end to military repression, and a ceasefire came into effect twelve days later, leaving the group in control of several autonomous zones—estimates range from 750,000 acres to approximately the size of the state of Maryland. It was then, through television, radio and newspaper, the world first met the man who would be called Marcos.

It is no coincidence that the Zapatista military front launched its armed rebellion on the first day of January, the very same day the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) became a reality. To the Zapatistas, it was the most recent development in a centuries-long process by which subsequent governments—Spanish, French, Mexican, and American—had rendered Mexico’s indigenous communities invisible. Thus, in the words of Marcos, this revolution required its combatants to “cover their faces to show themselves to the world, and take off their ski masks to hide from the enemy.”

According to Marcos, the indigenous revolution required its combatants to “cover their faces to show themselves to the world, and take off their ski masks to hide from the enemy.”

The Zapatistas were a coalition of Mayan indigenous communities in Chiapas. The rebellion received unprecedented popular support, not only among Mexico’s working, artistic and intellectual class but across the world. In part this was due to the Zapatistas’ message—that colonization by the Spanish 500 years before had set the world on a path toward globalization, and it was indigenous groups like their own who had been enslaved, their labor exploited and cultures and languages systematically suppressed. But many people were also enchanted by the charismatic spokesperson who called himself Subcomandante Marcos and delivered poetic pronouncements from behind a balaclava, the black ski mask ubiquitous of bank robbers, hijackers and Pussy Riot. Often described as a modern Che Guevara, Marcos was clearly not indigenous—he had light skin, hazel blue eyes, and spoke not with the high pitch accent of those indigenous to the southern jungles, but a soft middle-class accent common to the cities and those with formal education. His presence was an enigma: a sexy philosopher wrapped in bandoliers standing alongside dark-skinned Indians who have been systematically oppressed for centuries.

“Accustomed to looking down on the indigenous from above, they didn’t lift their gaze to look at us,” Marcos explained in a speech in May 2014. “Accustomed to seeing us humiliated, their heart did not understand our dignified rebellion. Their gaze had stopped on the only mestizo* they saw with a ski mask, that is, they didn’t see,” he continued.

Marcos fed the press with a barrage of missives—public letters, manifestos, essays and private letters later publicized. The first was published January 2, 1994, the day after the rebellion began, and detailed the Zapatistas’ declaration of war and revolutionary laws. Later followed: updates on peace negotiations; letters of solidarity with political prisoners across the globe, including American prisoners Mumia Abu-Jamal and Leonard Peltier. Meanwhile, the Mexican government and international media sought to identify the masked man. In 1995, then-Mexican President Ernesto Zedillo announced on live television that Marcos was born in 1957 to a middle-class family from the northern border state of Tamaulipas. He is reported to be a graduate of a Jesuit high school; holder of degrees in philosophy from the National Autonomous University of Mexico, or UNAM. Yet months after the rebellion began, in March 1994, Marcos “revealed” to the Mexican newspaper La Reforma—remember those warnings?—that he was a winger, a “reserve for the reserve,” for the second team, a youth division of Los Rayados de Monterrey.

Marcos joked that the Zapatistas hadn’t lost—they just didn’t have enough time to win. A 3-5 final score in a meeting between Zapatistas and members of Mexico’s national squad, who were led by Javier “El Vasco” Aguirre. The match was staged in March 1999 at la Ciudad Deportiva de la Magdalena Mixhuca, a massive municipal sports complex in Mexico City. A photo of the Zapatista team made the front page of La Jornada, one of Mexico’s leading leftists newspapers. Ten men stood, bodies at attention and left arm raised in salute. They wore simple black jerseys adorned with a single red star and stenciled letters EZLN, the acronym of El Ejercito Zapatista Liberacion Nacional, or the Zapatista National Liberation Army. The most striking detail: the ten men wore black balaclavas with red neckerchiefs, or palicates, wrapped around the neck—a common custom in the countryside to protect the neck of a shirt from the sweat of the day. The few photos from the game reveal that neither the masks nor palicates were removed for play.

Press reports included the game as a single sentence amid the bigger news of the day: 5,000 masked Zapatistas had arrived in Mexico City ahead of a national referendum on indigenous rights—the public ratification of the San Andres Accords, which outlined land reform and indigenous autonomy. Just a few days later, on March 21, 1999, over three million Mexicans voted in support of the Zapatista proposal.

Without proper context, the match may seem an anomaly, but the value of soccer to the rebellion had been put to pen and paper, shared with the public years earlier. In 1996 Marcos had written to Eduardo Galeano, one of Latin America’s leading popular historians and the hemisphere’s greatest writer on fútbol. Under the auspices of a letter, later made public, about the lives of Zapatista children, Marcos introduced readers and the world to a young indigenous player by the name of Olivio. Olivio was a Tojolablal child less than five years old. Marcos noted that children that age in this part of Mexico don’t often live beyond five years. Mortality among Mexico’s indigenous is higher than the mestizo population—in Chiapas nearly double. But there was Olivio, pestering a Zapatista commander who kicked the ball away to divert the child. Olivio gave chase to the ball through mud and muck, past the defenders—a tree and two children who were more interested in exploring the mud. Marcos watched the young fútbolista, waiting for him to score. But the young player stopped his dribble. He became distracted by a bird which could feed others. Olivio abandoned the game for a gun to hunt the bird. Admittedly, Marcos writes Galeano, the scene is a simile. In Spanish, he explained that this scene was not mean to cause concern but rather to illustrate that today’s soldiers wore their military uniforms so tomorrow’s children can wear wear a fútbol jersey—or anything but fight.

Others came in person to witness the Zapatista rebellion and, in the process, experienced Zapatista fútbol. In 2001, an amateur team from Bristol, England, arranged a solidarity tour to visit Zapatista communities in Chiapas. Among that group was a young artist who painted a few murals in Chiapas, according to the authors Will Simpson and Malcolm McMahon. One mural of his portrayed his club’s slogan: Freedom through Football. After the tour, the artist stenciled a design onto t-shirts and sweatshirts that his club sold for charity. The image is instantly iconic—a balaclava-clad Zapatista with a rifle strapped to his back, doing a bicycle kick—and so is the artist. Within a few years, the world would come to know him as Banksy.

In 2005, Marcos collaborated with the Mexico City novelist Paco Ignacio Taibo II on a series for La Jornada that was later compiled into a novel. Among the writing is a scene involving a soccer match between Zapatistas and a group of internationalists–“Zapatista Campamenteros”–on a visit to the region. The game took place on Zapatista territory, specifically in a paddock, among the mud and shit.

“What you have to do is change the game.

Pretend you’re going one way,

but really you’re going another.”

“In that soccer thing I learned what those Zapatistas call ‘the resistance,’ says the narrator, one of the visitors. According to the narrator, the Zapatistas concede two goals in the first 10 minutes and decide to retreat into defensive positions, leaving the internationalists, including two leggy Danes, to traverse the soak earth, the mud and shit.

A few minutes went by and then what happened, happened, continues the narrator. Our team, which was doing all the running around, began to show signs of fatigue…and then—again without any overt signal—wham, the whole Zapatista team hit me. They scored seven goals in twenty minutes and the spectators went wild, cause you know they were all rooting for the local team.”

But the boldest statement came that same year in the form of a letter to Massimo Moratti, the president of FC Internazionale in Italy. A year before Inter had pledged money and support to the Zapatistas, and the same year Milan played in the Champions League Final, Marcos invited the team to compete for a new cup: El Pozol de Barro. Again, context: the invitation followed Inter-Milan donations, including an ambulance and changing room fines, organized by then-captain Javier Zanetti, whose own non-profit foundation sent aid to the region in rebellion.

Following Inter’s generous support, Marcos proposed that together the teams would tour the Western Hemisphere, staging games in Mexico City, where they would witness the displacement of indigenous. Then to Guadalajara, where they would play for prisoners. Diego Maradona, Javier Aguirre, Jorge Valdano, and Brazilian midfielder Sócrates would be invited to officiate. Eduardo Galeano and Mario Benedetti would be asked to narrate for the Spanish broadcast. The Italian commentators would be Gianni Miná and Pedro Luis Sullo. Queer and transgender people would be invited to balance the heterosexist commentary and advertising at Mexican games and broadcasts. The next game would be in Los Angeles, California, in support of undocumented people, raise awareness for Mumia Abu-Jamal and Leonard Peltier and against the MinuteMan Project, a group of vigilantes who sought to halt immigration into the United States. From there, the game would travel to Guantánamo, Cuba. Then a pair of games in Italy: preferably Milan and Rome, in support of Europe’s emigres. The series would conclude in Euzkal Herria—Basque territory. It would be a seven-game tournament decided by the winner of four games. There was one caveat: if the Zapatistas lose more than three games, the tournament would be cancelled.

Of course the games never happened. But since 2010, Inter Milan has organized weeklong training camps for Chiapas youth, particularly girls, in occupied territory.

In October 2016, Marcos—now Subcomandante Galeano—published a letter online to the Zapatistas’ website. Entitled “Questions Without Answers,” its second section was even more opaque. The subheading was simply three names: Defensa Zapatista, Chicharito Hernández, and Lionel Messi.

The section begins with another scene deep in the Lacandon. Galeano absorbed in social media, online and the news, absent from his actual physical setting. A girl of eight or 10 approaches him, searching for an errant ball that veered off her mark. She glances at the screen of his laptop. We do not know what she sees. Then she randomly says, “It’s like the thing with Chicharito and Messi.” Her voice and presence startles the Zapatista spokesman, who asks her, not only on his behalf but also for the reader, to explain.

But her explanation is only more confusing.

“It’s like they’re criticizing Chicharito for not scoring goals for Barcelona and Messi for not doing anything to help the Jaguars. Some say that Chicharito is going to recover; others say he’s done. Some say that Messi is sad because his home country doesn’t support him; others say it’s that his shoe is too tight and if he changes it he’s going to shoot well again. But the thing is Chicharito doesn’t play for Barcelona, nor Messi for the Jaguars. Meaning, they’re getting all worked up for nothing.”

Galeano is caught in his own trap. The young girl is mixing fact and chisme just as Marcos once did with the press, consciously showing confusion while making a statement obvious to her.

As Galeano considers her words, she suggests that they get back to organizing a soccer team. “There aren’t too many fútbolistas now,” she says. “But there will be more to follow.”

As the child leaves, she tells Galeano that if her mother comes looking, to remind her Chicharito doesn’t play for Barcelona and Messi doesn’t play for the Jaguars. Don’t lie, she adds, “…What you have to do is change the game. Pretend you’re headed one way, but really you’re going in another.”

The girl’s name was Defensa Zapatista. Unlike Olivio, Jeniperr, Jorge, or Chelita – other children, with common names, who have appeared in Marcos’ writing. If Defensa Zapatista is, as he estimates, between eight and 10 years old, she was born into a community nearly fifteen years into rebellion. She was born into war. That is her reality.

The games are real. The war is real. The solidarity exists. The images are remembered. But someone told the story. It doesn’t matter if his name is Marcos, or Galeano, or Rafael Sebastián Guillén Vicente, as the Mexican government claimed in 1995. The reader responds to his words—whether intrigued by the simile or because we are going to organize a fútbol match against the wishes of a government. Like a game of fútbol, the decision to act is all that matters.

Contributors

George Sanchez-Tello

Author George B. Sánchez-Tello comes from families that lived with the land in both New Mexico and Guatemala. Born and raised in Los Angeles’ San Gabriel Valley.

Muti

MUTI is a creative studio founded in 2011, based in the city of Cape Town, South Africa.

TAGS