Arthur Pember and His Code

October 15, 2022

This extraordinary remembrance of soccer pioneer Arthur Pember originally ran in slightly different form in Howler 10, Spring 2016.

It’s longer than most web pieces, and we considered running it in two or three parts, but it deserves to live here in its remarkable entirety.

ARTHUR PEMBER titillated Victorian New York with his muckraking journalism, but there is one episode he never wrote about: serving as the first president of the English Football Association, under which the rules of soccer became enshrined.

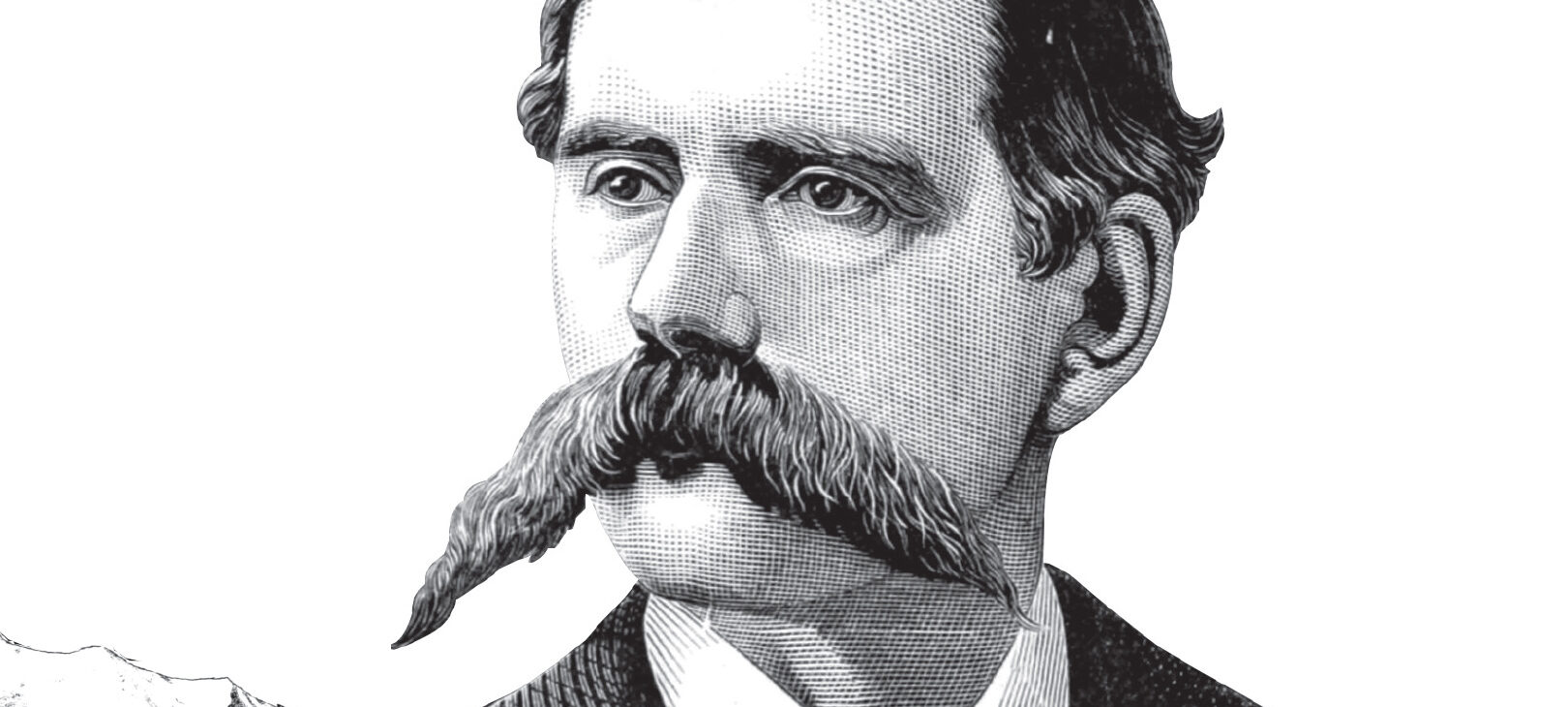

STANDING ON A SLOOP off the southern tip of Manhattan on a pleasant April morning in 1873, Arthur Pember lowered a 25-pound brass helmet onto his head and fixed it to the collar of his waterproof suit with 12 nuts and bolts. His suit was made of layered canvas and India rubber. Beneath it, Pember wore a thick woolen shirt, underpants, and stockings; his waterproof gloves were secured to his sleeves with brass rings. On his feet were lead-soled boots that weighed 16 pounds. A further hundred pounds of lead weight were strapped to his chest. No one had ever weighed his mustache, but it was at least 10 inches long. Through the round glass window on the front of his helmet was a paddle-steamer vision of New York Bay. The Statue of Liberty was still a figment of a Frenchman’s imagination; the Brooklyn Bridge was in its earliest underwater stages of construction; and there were no high-rises on the New York skyline. The city’s tallest structures were church spires, rivaled only by the masts of hundreds of sailing ships docked hull-to-hull along Manhattan’s piers.

Pember was 38 years old, strong and intrepid. He was an English journalist who worked for The New York Times, the Tribune, and several other of the city’s publications, an investigative reporter known for his adventurous stories, and there was much adventure to be found down in the crime-ridden and disease-infested streets of Lower Manhattan. Today, his reporting would take him to new depths.

“The part of the bay in which I took my underwater stroll was that off the Battery,” he later wrote, “where the mighty currents of the Hudson and East Rivers expand into the open bay, bringing with them a rare and unique collection, consisting of dead cats and dogs, the sewage of the east and west sides of New York, the refuse of Fulton, Washington and other markets, and a variety of other interesting materials and ingredients, too unsavory to dwell upon and too numerous to recapitulate.” Nevertheless, he was eager to enter the water: “I was burning with an insatiable desire to investigate Mr. Davy Jones’s Locker.”

“I was burning with an insatiable desire to investigate Mr. Davy Jones’s Locker.”

Pember was searching for the underwater creatures he had read about in the fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen, the ladies of the sea who wore oyster shells and combed their hair with pieces of reef coral, who drew men underwater with their beauty and their song and kept them forever as prisoners. The presence of these mythical creatures was not confined to fairy tales. New York’s newspapers were reporting strange sightings, and a great showman was exhibiting a mysterious specimen in a glass case. Pember was searching for mermaids.

Early games were played with an inflated ox bladder for a ball on a field with no markings by teams of indeterminate numbers with no goalkeepers and no referee. It was football, not soccer; soccer did not yet exist.

In the course of his work, Pember had braved murderous gangs and a crooked police department to write about the scam of New York’s panel houses, where clients, lured by promises of prostitution and gambling, were beaten and robbed. He had gotten himself arrested in order to investigate the brutal and dehumanizing conditions at the Ludlow Street Jail, the city’s corrupt federal prison. He had gone undercover as a coal miner, a circus worker, a street-hawker, and—for a series of acclaimed articles—a homeless vagrant living among the city’s poorest souls. Pember had exposed bogus doctors, peep-show operators, and spirit mediums. He had written about many things, but one thing he never wrote about was the game he had helped create in an earlier part of his life. He never wrote about soccer.

A DECADE EARLIER, in January 1863, Pember had stood on a steeply banked, wintry field in the grounds of Oaklands Hall, a gothic mansion in Kilburn, northwest London. He was among a group of young men, members of two fledgling clubs in London’s emerging football scene, dressed in an assortment of knitted jerseys, long trousers, stockings, walking boots, and caps. They drove sets of goalposts into the muddy ground at opposite ends of the field. Then a ball was thrown into the air, and they began to play.

The 28-year-old Pember was the captain of the NNs, which stood for “No Names,” or, according to one London newspaper, “No Nothings.” He lined up alongside two of his brothers: Edward, two years older, was a respected lawyer; George, just 18, was already an established footballer, having played in several “top class” matches. Other teammates included Alec Morten, who would go on to captain the England national team 10 years later, and Alfred Baker, who would score England’s first international goal, in 1870.

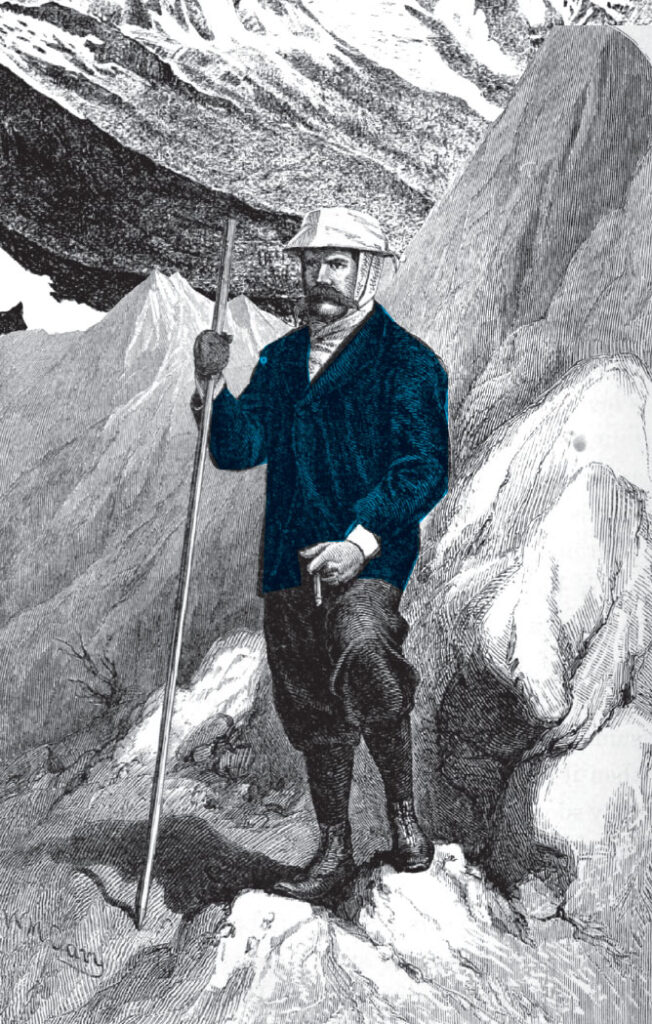

Pember was himself a notable figure in London society after he became, some years earlier, one of the first Brits to scale Mont Blanc, the highest mountain in Europe. Born in 1835 in Brixton, South London, the son of a wealthy stockbroker, he was educated at home by his family’s governess and, unlike his brothers, did not attend university. He first saw Mont Blanc on his grand tour and returned several years later to try to reach the summit. He and his climbing companions—two guides, four porters, and a white French poodle named Bouquet—negotiated treacherous glaciers, crevasses, and ice walls until they reached the top. The ascent had been difficult, but the descent proved almost impossible. Pember and his companions survived multiple avalanches and were almost blown from the mountain by a hurricane. Eventually, they found themselves trapped on a cloud-bound glacier, with zero visibility, as a deadly thunderstorm rolled in—only to be led to safety by Bouquet. His account of the adventure became the basis of a popular lecture he would give both in Britain and in the United States.

Returning to London as something of a hero, he took a job with his father and set up a home in Kilburn. He married in 1860, but his wife died just nine months later, following a miscarriage. In 1862, Pember married 17-year-old neighbor Alice Grieve. He also cultivated a mustache that was extravagant in its dimensions even by Victorian standards. Meanwhile, influenced by his brothers and work colleagues, Pember became involved in football.

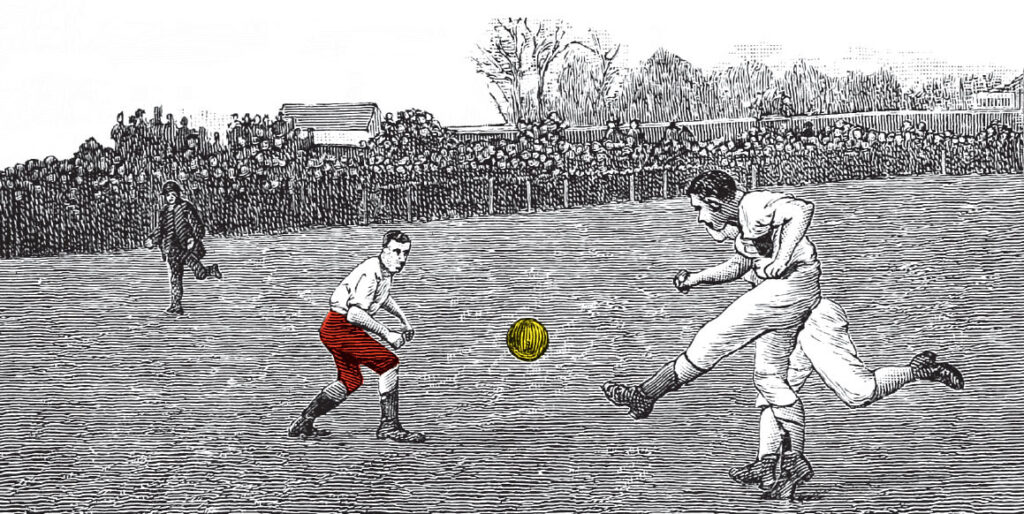

The 1863 match was the first NN game on record. The opponent was Barnes FC, a team captained by an attorney named Ebenezer Cobb Morley. The NNs won 4–0. The goal scorers aren’t recorded, nor are any other match details, but we can assume it would have been a confusing spectacle for fans of modern soccer. Early games such as this were played with an inflated ox bladder for a ball on a field with no markings by teams of indeterminate numbers with no goalkeepers and no referee. It was football, not soccer; soccer did not yet exist.

Football had yet to be separated into its three major codes—soccer, rugby, and American football. Instead, throughout a variety of towns and institutions there existed a multitude of rulebooks, each containing different elements of the three codes. Cambridge University played a kicking game; the Rugby public school (where the sport of rugby would later be born) allowed players to handle the ball; and matches in the town of Sheffield could be won by touchdowns. When rival clubs played each other, rules needed to be agreed upon in advance. These negotiations often proved difficult—some clubs enjoyed hacking and handling, while others, including the NNs, preferred a more refined kicking game. When the NNs played Barnes for a second time, for example, they won 2–0, but a third goal was disallowed after it was “technically objected to by the Barnes men.” In order for the sport to grow in any meaningful way, Pember and Morley realized, it needed a universal rulebook, and the two men set out to create one.

In October 1863, Morley posted a small ad in London’s sporting newspapers: “FOOTBALL—A MEETING will be HELD at the Freemasons’ Tavern, Queen-street, Lincoln’s Inn, on Monday, the 26th instant, at 7 o’clock pm, for the purpose of promoting the adoption of a general code of rules for football, when the captains of all clubs are requested to attend.”

FOOTBALL

“A MEETING will be HELD at the Freemasons’ Tavern, Queen-street, Lincoln’s Inn, on Monday, the 26th instant, at 7 o’clock pm, for the purpose of promoting the adoption of a general code of rules for football, when the captains of all clubs are requested to attend.”

The Freemasons’ Tavern was part of a grand three-story Masonic temple in the heart of London, a short walk from the hectic flower and produce markets of Covent Garden. This was the gaslit Victorian London of pickpockets, poorhouses, and Pickwick clubs—the London of Charles Dickens. The captains of local clubs gathered in one of the tavern’s woodpaneled meeting rooms. In a reflection of his high standing in the football community, Pember was invited to chair the event.

“His idea was,” the Sporting Life newspaper reported, “that the captains of all clubs should put their names down as members of a society to be called the Football Association.”

After putting “himself prominently forward,” Pember was appointed the association’s first president, Morley its secretary. Eleven clubs agreed to become founding members, but not all those in attendance supported the venture. The fledgling organization faced formidable opposition, most notably from the public schools.

In the U.K., traditional public schools are elite, fee-paying institutions. They held—and still hold—great power and influence because of the proliferation of their “Old Boys” in high society. (Then prime minister Lord Palmerston was an Old Boy of Harrow. Current prime minister David Cameron is an Old Boy of Eton.) Steeped in tradition, the schools were fiercely protective of their own football rulebooks and did not take kindly to the meddling of outsiders.

The only public school present at the meeting was Charterhouse, represented by Bertram Fulke Hartshorne, a 19-year-old upstart later described by a relative as “an appalling snob.” While Hartshorne declared his support for the formation of a football association, he felt the public schools should “take a prominent part” and said Charterhouse would not join unless that was the case.

Pember was well educated, but he was not a public school man. He had seen public school alumni take control of many aspects of English society—politics, the economy, the military—but he was not about to let them take control of football. Every association must have a beginning, he said, and he hoped the public schools would come around. If they didn’t, he intended to maneuver them out of the way.

IN A SERIES of meetings through the end of 1863, the newly formed Football Association began to set out its universal rulebook, which it had christened “the Laws of the Game.” Initial discussions set the length of the field at 200 yards and the width at 100 yards, much larger than modern dimensions. The width of the goalposts would be eight yards—as it is today—but there would be no bar or tape across the top, meaning goals could be scored at any height. Teams would change ends after each goal. There was no halftime, no prescribed match length, nor a prescribed number of players.

Most notably, the initial rules allowed players to handle the ball by way of a “fair catch”—although players were not allowed to run with the ball in their hands. Handling was a divisive issue, but it was not nearly as divisive as hacking. In fact, the standoff between hackers and nonhackers threatened to tear the universal rulebook apart before it had even been finished.

Hacking was defined as “kicking an adversary on the front of the leg, below the knee.” Like corporal punishment and “fagging” (where young boys were required to act as servants for older pupils), it was a tradition in the public schools, where roughhousing and bullying were accepted parts of life. Many of those who had played football at public school saw hacking as absolutely integral to the game. Yet Law 10 of the association read, “Neither tripping nor hacking shall be allowed.”

“Hacking is the true football game,” claimed the wine merchant and public school Old Boy Francis Maule Campbell, who was the captain of Blackheath and, of course, a notorious hacker himself. Nonhackers, he said, did not truly appreciate the “spirit of the game which was so fully entered into at the public schools and by public school men in after life.”

Pember strongly disagreed. He called hacking “a very brutal practice” and pointed out that not all public school men were hackers. He was the only member of the NNs who had not attended public school, he said, but his teammates were all “dead against” hacking.

“Be that as it may,” responded Campbell, according to accounts of the meetings published in London’s sporting newspapers, “I think that if you do away with hacking you will do away with all the courage and pluck of the game, and I will be bound to bring over a lot of Frenchmen who would beat you with a week’s practice!” If hacking was outlawed, Campbell said, Blackheath would withdraw its membership and set up its own association.

Pember accused Campbell of blackmail, saying, “It certainly is not, in my opinion, a fair and honest way of dealing.”

Morley, who, like Pember, was not a public school man, said that while he personally had nothing against hacking, it would be a “death-blow” to the association if Blackheath were allowed to have its way.

Campbell requested an adjournment so that he could get representatives of the public schools to support his argument. But Pember insisted on pushing through an immediate vote, and hacking was banned.

The first official game under the new rules—the first official game of association football—was played on January 9, 1864, in Battersea Park, between the President’s side, captained by Pember, and the Secretary’s side, captained by Morley. Both captains “especially distinguished themselves,” according to the report published in Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, in a game that Pember’s team won 2–0, with both goals scored by 20-year-old Charlie William (C.W.) Alcock. In the evening, the members of the Football Association dined together at the Grosvenor Hotel on Buckingham Palace Road. As president, Pember raised a toast: “Success to football, irrespective of class or creed.”

PEMBER CONTINUED to play for and captain the NNs, and he also played for Wanderers, an influential touring side that would go on to win the first FA Cup final in 1872. Then he made a typically adventurous decision: he would immigrate with his family to the United States. In 1867, he ceded the presidency of the Football Association to Morley, and young Charlie (C.W.) Alcock became secretary. A year later, Pember, his wife, and their three sons left football and London behind and boarded a steam-powered ocean liner for New York.

In subsequent years, Alcock would rise to the top of the Football Association as it expanded its membership base and refined its rules. Handling was eventually outlawed, field dimensions diminished, crossbars added, and the 90-minute, 11-versus-11 format defined. Alcock initiated the FA Cup competition, arranged the first international matches, and pushed through the legalization of professionalism, precipitating the formation of the Football League in 1888. Although he had not been directly involved in the formation of the Football Association or the creation of the Laws of the Game, it is C.W. Alcock, not Arthur Pember, who has come to be remembered as the father of football.

Meanwhile, the public schools continued to play their own separate games. Blackheath and its fellow hackers favored the Rugby school rulebook and formed a rival association called the Rugby Football Union. In the U.S., college teams borrowed from both the association and rugby games as they developed their own code of football. In England, at Oxford University, an association football enthusiast and future England captain named Charles Wreford-Brown was credited with creating the abbreviated term “soccer.”

In New York, Pember toured the lecture circuit with his well-received adventure talk “Up and Down Mont Blanc.” Then he began to write, first for the New York Standard, then the Tribune and the Times, contributing descriptive sketches of workplaces and other institutions that gradually took on an investigative nature and eventually became undercover exposés. He became known for wearing disguises, which were apparently successful in spite of his refusal to alter his distinctive mustache. Then, in April 1873, he found himself on a sloop off Manhattan, searching for mythical ladies of the deep.

The New York press was fond of tales of mermaids. The great showman P.T. Barnum had exhibited in the city a specimen known as the Feejee Mermaid, a desiccated half mammal, half fish that had apparently been found in South Pacific waters near Fiji. In 1869, it was revealed during a court case that the mermaid was a hoax. In 1870, the Tribune reported that a “real mermaid” had been found in the sea near Japan and was being displayed at a bazaar in Delhi. “I saw the animal and felt it with my own hands,” wrote the newspaper’s correspondent. “I couldn’t make out anything fictitious about it.” In 1873, the year of Pember’s dive, the Times reported that a “supposed mermaid” had been sighted by a woman and several children on a beach at Brewster, near Cape Cod. The creature had the body of a fish and a head that “resembled exactly that of a child.”

Pember’s exploration was a product of this public fascination. He stepped over the side of the sloop and climbed down the short ladder that hung from the boat’s gunwale. Gradually he slipped into the water until fully immersed. It was then that he felt a terrific stab of pain to his head. “I felt as though someone had run an iron rod clean through my head from one ear to the other,” he later wrote. The pain—caused by the pressure of compressed air being forced into his helmet—only increased as he sank lower and lower into the deep: “It seemed as though my cranium must explode, like an engine boiler, and that the drums of my ears would certainly burst.”

He was about to pull the signal rope to be hauled back up to the boat when his feet touched the river bottom. “I stood perfectly still for a while,” he wrote, “and the pressure on the brain from the compressed air soon began to decrease.” Then he began to hear the faint sound of music—not, to his disappointment, the “dulcet and harmonious” tones of a “mermaid on a dolphin’s back,” but simply a ringing in his ears caused by the buildup of pressure. So, gathering his senses, he began to explore the depths. If Pember did not find any mermaids, he did at least hope to see fish, or, he admitted, “dead bodies.” But he was astonished by his total inability to see anything at all in the murky depths. “I could not even see my hand when I put it before the glass window in the helmet,” he wrote. After a few minutes of “groping blindly in the darkness,” Pember pulled the signal rope and was hauled swiftly onto the boat, where his helmet was removed: “What a long breath I drew!”

“I can vouch for the fact that there are no mermaids in New York Bay, at least not in that part of it which I explored,” he wrote. “If any one will take the trouble to follow my example, and go see for himself, I think he will agree with me that the bottom of New York Bay is about the last place in the oceanic world which the mermaids would select for their marine residence; that is, if they were proper-minded mermaids.”

Pember’s mermaids sketch was among the last he wrote for the New York press. In 1874, he published a collection of his writing, The Mysteries and Miseries of the Great Metropolis, With Some Adventures in the Country: Being the Disguises and Surprises of a New-York Journalist, credited to “A.P., the Amateur Vagabond,” a semi-anonymous name that referenced his popular undercover series on down-and-outs. “I have submitted to many inconveniences and faced dangers while pursuing my adventures,” he wrote in the preface, “but how could I possibly pen sketches from real life had I not been ready to do so?” The Times said each chapter was “a brilliant picture of actual life.”

Pember continued to write occasionally for the Times and also worked at the Museum of Natural History. But following the death of his wife in 1881, he soon became sick himself. In 1884, after, one colleague wrote, he had been told by a doctor “if he did not cease pumping his brains into a daily paper, his heart would soon stop pumping blood to his brains,” he moved with his five sons to a farm in LaMoure, North Dakota. He began work on a new book, Twenty Years in New York Journalism. It would never be published. Arthur Pember died on April 3, 1886. He was 50 years old.

In the week before his death, the Times reported a meeting of area football clubs “playing according to association rules” for the purpose of forming a New York football association. Pember’s universal rulebook had followed him over the Atlantic, but his role in its creation had already been forgotten.

“Formerly a writer on the New York press … he was an Englishman by birth,” read his brief Times obituary. “His death was the result of kidney difficulties, supplemented by blood poisoning from a carbuncle in the lumbar region.” There was no mention of mermaids, or soccer.

Contributors

Paul Brown

Paul Brown is the author of Savage Enthusiasm: A History of Football Fans. He can be found at @paulbrownUK and www.stuffbypaulbrown.com.

Archive Art

Art: NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY · THE MYSTERIES AND MISERIES OF THE GREAT METROPOLIS: WITH SOME ADVENTURES IN THE COUNTRY : BEING THE DISGUISES AND SURPRISES OF A NEW-YORK JOURNALIST BY ARTHUR PEMBER NCSU LIBRARIES · INFORMATION AND LIBRARY SCIENCE LIBRARY, UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL SMITHSONIAN LIBRARIES · THE BRITISH LIBRARY

TAGS