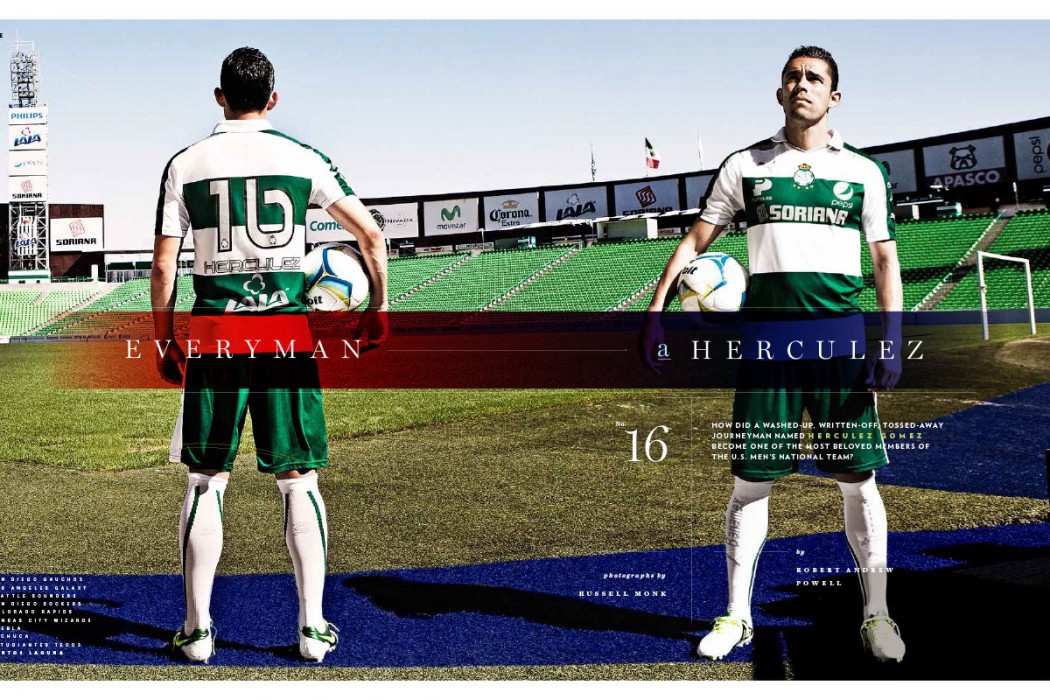

How did a washed-up, written-off, tossed-away journeyman named Herculez Gomez become one of the most beloved members of the U.S. Men’s National Team?

by Robert Andrew Powell | photograph by Russell Monk

WHO SAW THIS COMING? Who bet he’d be training here, at Estadio Azteca, one day before a friendly between the U.S. men’s national team and the national team of Mexico? His American teammates circle midfield, stretching calves and hamstrings. Reporters throng four deep along a barricade behind the north goal — the same net Diego Maradona shook with his Hand of God — where they gather quotes from the two Americans presented for interviews. One of them, goalkeeper Tim Howard, is asked about playing in this stadium, what’s the vibe he gets from Mexican fans, and he says, “Contempt.” The other player facing the cameras is Herculez Gomez.

He speaks in measured clips, carefully avoiding incendiary statements. More than once, he repeats a question to make sure he’s feeding a story line he agrees with. There are reasons why Herc is taking questions. His parents are Mexican. He plays in Mexico for Santos Laguna, a championship-winning team, and he was once the top scorer in the Mexican league. He’s unusually articulate in both Spanish and English. And yet, he’s an unlikely spokesperson. He’s 30 years old. The longest he has stayed with any professional club is just two seasons. To this point, he has played in only 13 national team games, total. This will be his first game for the U.S. at the Azteca. So many other players on the roster have more international experience. Landon Donovan is over there stretching at midfield, but it’s Herc serving as the American ambassador.

Did anybody predict his rise? Herc wasn’t the most talented player on his youth team. Even now he starts irregularly for Santos. Over the years, coaches have advised him to quit the game. They’ve lowballed him in salary negotiations or traded him away after an injury. So many times Herc has proven his doubters wrong, so many times he’s persevered and ultimately triumphed, that I’ve learned to suppress my own niggling questions about just how good a player he is. Is he really the guy we want leading our attack? Can he help get us to Brazil? Watching Herc address the press thrills me, I must admit. He’s my favorite athlete on any team or, really, in any sport. His journey from obscurity to this intimidating stadium — as the face of the national team, at least for today — inspires me. Herc’s story has inspired me for a couple years by now, and helped me push through a particularly low moment in my life. When I watch Herc, I focus on the way he hustles and grinds and draws fouls and basically makes a pest of himself. Most often, though, the nuances of his play fall away. I dwell on the big picture, on his journey, and on how much energy I get back from him every time he takes the field.

IT WAS MAY 2007 when I discovered Herculez Gomez. He was playing for the Colorado Rapids, and I was having one of those how-in-the-world-did-I-end-up-here moments. I’d moved to Boulder, Colorado, about a year earlier, after my marriage had failed in Miami, and after my career, such as it ever was, stopped all forward progress. I’d planned to write a book about long-distance running but that project wasn’t showing much promise. Mostly I was lost. To cut into the debts piling up, I freelanced a few newspaper articles when I could, including one about the arrival in Major League Soccer of a certain midfielder named David Beckham.

He’d just signed with the Galaxy, the Rapids’ opponent that night. Though Beckham wasn’t in the lineup, and hadn’t even made the trip to Denver, I was asked to record whatever buzz might be floating around Dick’s Sporting Goods Park. It was my first Rapids game, and my first MLS experience since the Miami Fusion folded. There wasn’t all that much Beckham buzz, and the game, a Rapids win, wasn’t all that notable. I was in the press area afterward, sitting with the regular beat writers and trying to figure out my story, when the night’s lone goal scorer stepped forward for an interview. I wasn’t really paying attention.

”When I was in labor, it was a struggle, just physically”, says Juanita Gomez, his mother. “The doctor says, ‘Oh, he’s strong, he’s a Hercules’. And Herc’s father had been watching a movie about Hercules in the waiting room, which he saw as a sign.”

“It’s no secret I want the finer things in life,” Herc said soon after he started speaking, “and if I keep playing well, I’ll get them.” That was it. That sentence — that casually volunteered ambition — caused me to look up from my notebook to see who this guy was. He was lean, with a narrow face, thick eyebrows, and jet-black hair inclined to curl. He referred to his time in L.A. — apparently he had played for the Galaxy — as an internship. It had been impossible for him to be the man in L.A. while playing alongside Donovan. Denver, he said, gave him a chance to stand out. He spoke clearly, and when the questions shifted into Spanish, he handled them in the same bright voice. He claimed to be a risk taker, a player who will try that bicycle kick anytime: down four, tied game, whenever.

Nothing here seems that remarkable, I recognize. In context, though, Herc stood out. He came across as introspective — which is so rare in sports — intelligent, and hungry. He wants the finer things in life! I cornered the Rapids’ press guy, who told me Herc was somebody worth getting to know.

Herc (his preferred name; “Herculez” is what his parents employed when they were punishing him) was born in East L.A. His father, Manuel, had immigrated to California from Jalisco, Mexico, intending to be a seminarian. That career choice didn’t stick, and when Manuel was introduced to the daughter of a colleague — she was also a Jalisco native — he fell in love, won her over, married her, and, as Herc says, they began cranking out kids. Herc, the firstborn of five, was supposed to be called Ivan.

“That was the name I wanted,” says Juanita Gomez, his mother. “That or Manuel, after his father. But when I was in labor, it was a struggle, just physically. The doctor says, ‘Oh, he’s strong, he’s a Hercules.’ And Herc’s father had been watching a movie about Hercules in the waiting room, which he saw as a sign. He said, ‘We’re going to name him Herculez, and with a “Z” so everyone will say “Herculezzzzzzzzzzzz.”’ I told him, ‘Are you joking? No way!’”

The nurses agreed with Juanita. Several times, over multiple days, they marched into her room to demand the Herculez name be changed. They confronted Manuel but he wouldn’t budge. “He laid a guilt trip on me,” Juanita recalls. “He said he’d spent three days in the waiting room, and it was his son, and so I let him have his way. The hospital waited eight days before they signed off on the paperwork!”

Manuel worked on Herc’s soccer development in the crib, bending and straightening the newborn’s legs. When Herc started walking, he encouraged him to dribble a soccer ball as he waddled around his grandmother’s living room. There’s a picture of Herc when he was two years old, striking a ball with technical perfection. Once when his grandmother returned home from an errand, all the photos and paintings were knocked off the apartment walls. Herc had started kicking the ball with real force, to this day his bread and butter.

The Galaxy noticed him in San Diego, signed him to a development deal, and gave him a ring when the team won the MLS Cup in 2002. Less gloriously head coach Sigi Schmid shared a bit of career advice: find another line of work, kid — soccer’s not in your future.

Soccer gave Herc’s life some stability as his father hustled a string of hopeful ventures in Oxnard, the California farming community where the family relocated for a few years and where Herc started playing the game in earnest. Manuel sold sporting goods. He opened an auto body shop. He peddled couches and kitchen tables. If one enterprise showed success, Herc’s father would diversify into another arena, hoping that he could build a small empire, a gamble that went bust in the recession of the early 1990s. There hadn’t been a single spectacularly bad bet or anything, just small and incremental losses until there was no more money. Or even furniture in the apartment. With the family down to just clothes and an old Astro minivan, Manuel packed everyone up and drove 320 miles across the Mojave Desert, gambling again, on a new life in Las Vegas.

“We didn’t know we were moving,” recalls Ulysses Gomez, Herc’s brother. “He told us we were going on vacation to Vegas, and we ended up staying there.”

Herc didn’t like Nevada. It was too hot, the new apartment was too tiny, and kids at school, amused by Herc’s first name, kept asking him to prove his strength. He stuck with soccer, winning a spot on Neusport, a traveling team. “He showed up at an open tryout,” recalls his coach, Frank Lemmon. “We didn’t know who he was, but we had a policy that we’d look at anybody. The first time he shot on net, he cracked a bicycle kick. My assistant coach and I turned to the side and gave each other cheeky high fives and said, ‘Yeah, he’s on the team.’” Herc clearly had ability, though Lemmon says he wasn’t a standout. (“I’d say he was no more than the fourth or fifth best.”) He graduated from Las Vegas High with all-state honors, but no college expressed real interest. There probably wasn’t anyone who projected him to make it as a professional player. His father, Manuel, encouraged him to take the gamble anyway.

“It was his destiny to play professionally,” Manuel tells me. “I knew he could do it.”

On the bus back to their Mexico City hotel, teammates laughed as the two kids in the Azteca parking lot threw up Herc’s trademark goal celebration, arms raised to showcase their biceps.

Herc was only 25 years old when I found him on the Rapids, but by then he’d already traveled a long road. He first flew to Mexico, trying out with Pachuca, where he was cut after two weeks. He spent two months with Cruz Azul before being cut again. He signed with a low-level team in Puebla that paid him $30 a month and stacked him in a players-only dormitory. (“It was Lord of the Flies in there.”) Wanting to play for a better club, Herc moved to Durango, which turned out to be a dead end. Back to Las Vegas to play in a rec league, then a spell in San Diego with a semipro team called the Gauchos. The Galaxy noticed him in San Diego, signed him to a development deal, and gave him a ring when the team won the MLS Cup in 2002. Less gloriously, head coach Sigi Schmid shared a bit of career advice: Find another line of work, kid — soccer’s not in your future.

“I didn’t know what else to do,” Herc recalls. “Soccer was kind of my ticket out, you know?”

On loan to the USL Seattle Sounders, Herc broke a metatarsal in his first scrimmage. A long rehab preceded a drop down to the San Diego Sockers, an indoor team that folded midseason. Herc moved back to Vegas to live at home — “that sucked” — until a friend encouraged him to try out again for the Galaxy. He rejoined the team, won another MLS Cup, and scored a championship-winning goal in the U.S. Open, earning a bronze gas mask trophy of appreciation from the supporters group known as the L.A. Riot Squad. Yet the Galaxy still shipped Herc and a couple other players to Colorado for goalkeeper Joe Cannon.

Soon after I discovered him at the Rapids’ stadium, he tore ligaments in his right knee. That basically was it for him in Colorado. “Herc was playing well, no doubt about it,” says former U.S. national team defender Marcelo Balboa, who played for the Rapids and still lives outside Denver. “But then he tore his ACL. I don’t care what anybody says, nobody comes back from an ACL mentally for at least a year. Not in full form.”

A year lost. Before he could recover, the Rapids traded Herc to the Kansas City Wizards. I’d followed his move, but he seemed to be floundering in Kansas City. Last I’d seen, he’d left the Wizards altogether. By then I’d moved back to Miami. No publisher wanted my running book, which left me with virtually nothing to show for three years of work. We both seemed to be washed up.

THE DAY AFTER the Azteca friendly, I fly a few hours north to Torreón, home of Herc’s club team. I remain high from a historic American win, the first ever on Mexican soil. Herc started the match and played 78 exhausting minutes before being replaced by Brek Shea, the midfielder who promptly engineered the game’s only goal. On the bus back to their Mexico City hotel, teammates laughed as two kids in the Azteca parking lot threw up Herculez’s trademark goal celebration, arms raised to showcase their biceps.

Herc has more than 60,000 Twitter followers. U.S. Soccer named him a finalist for the 2012 men’s team athlete of the year, which is remarkable considering how few games he’s played for the national squad. At the most recent World Cup qualifier, against Guatemala in Kansas City, the American Outlaws carried a banner of Herc into Livestrong Park. His Facebook page overflows with posts from fans who thank him for leaving everything he has on the field and from others telling him he’s becoming their favorite player.

“I think it’s ’cause he didn’t give up,” says his brother Ulysses, an MMA fighter who wears Herc’s jerseys into the ring. “People appreciate that.”

Torreón is dusty and dry and so corrupted by narcotraficantes that Herc won’t let me catch a cab to his house. This is only the fourth time I’ve seen him in person, and just the second time we’ve really spoken. I never got to talk to him in Denver. I first interviewed him briefly outside the soccer stadium in Puebla, where he went in 2010 to restart his career — to “flip the tortilla,” as his father puts it. My flight from Mexico City arrived more than an hour late, a delay I wasn’t able to relay before I had to turn off my phone. Which means Herc, this national-team starter with whom I’ve talked only briefly, waited for me in the airport parking lot all that time. He tweeted, texted, played Words with Friends, and when I stepped into his car apologizing like crazy, he brushed off my shame like the delay was no big thing.

I’m talking to him now in his black Audi SUV as we motor through the somewhat apocalyptic landscape where he’s lived for the past seven months. He’s wearing a trucker hat that advertises the State of California, as does his T-shirt. The Audi’s leather seats and push-button ignition and Bang & Olufsen speakers are obvious upgrades from the Saturn ’on he drove in Colorado. (The “I” had fallen off years earlier, in California.) There’s also a shiny black Camaro parked at his house, where I’ll be staying for the next five days. Yeah. Five days. When I’d sent Herc an e-mail asking if I could come watch Santos Laguna play a game, he not only encouraged me to fly in, he also insisted I stay at his place. No big thing.

Herc rents in a gated subdivision near Torreón’s bullring, just off the main road to the Santos stadium. The house is large. Four bedrooms feature walkin closets and private bathrooms with showers. The kitchen is huge and modern. A restaurant-ready gas range stands next to a stainless-steel refrigerator holding mostly bottles of water and Gatorade. There are so many ways to illuminate the space — even the cabinets can be lit up from within — that Herc can’t remember which switches control what lights. The clock blinks on the microwave. “I’ll be out of here by December,” he tells me when I ask about his stability at Santos. (Not true, actually. Santos will remain his team into the new year.)

Santos is a rising club that, the season before I visited, rose all the way to a championship, making Herc one of few Americans to win a top division championship outside the U.S. Oribe Peralta, probably the most popular soccer player in Mexico right now — he scored the gold-medal-winning goal at last summer’s Olympics — also plays for Santos, and in Herc’s position. Oribe usually starts, leaving Herc to enter most games as a super sub. He scores remarkably frequently for the minutes he plays, but he doesn’t play as many minutes as he’d like. In the previous season’s championship final, Herc didn’t even see the field. “I sometimes feel like an expensive backup plan,” he tells me.

The house’s main hall, just off the dining room, serves as a rec room. Three vaguely Picassoesque oil paintings hang on one wall, adjacent to a whiteboard on which Herc and friends have scribbled inspirational maxims.

“Dream as if you will live forever, live as if you will die today.”

“The night is always darkest before the dawn.”

Like many athletes, Herc fuels on these phrases. (Eddie Johnson is also a particularly keen affirmation hoarder.) Herc changes phrases on the board almost daily and tweets them out to his followers. “If you find yourself on the side of the majority, it’s time to reflect.” Is that self-help? Not everything on the board is. “Don’t bro me if you don’t even know me!” is also up there.

Two black leather couches frame a corner, facing a TV hanging from the ceiling. A cable box beams in soccer games from around the world, though Herc often uses iTunes to keep up with his favorite American shows: The Bachelor and Homeland. (“That show is crazy.”) A narrow bar hosts bottles of Johnnie Walker Red, Coca-Cola, and a local brand of mineral water. A dartboard — mandatory in a bachelor pad (“I do not want to be tied down right now”) — hangs on a wall behind the equally mandatory pool table, which lists to starboard. Closing out a wobbly game of eight ball when I walk in is Ugo Ihemelu, a longtime friend of Herc’s, his former teammate with the Galaxy and the Rapids, and currently the captain of F.C. Dallas. Ugo’s staying here all week — there is plenty of room — as he recovers from a concussion. We start the first night with pizza at a strip-mall restaurant where Herc knows the owner, sharing the pie with another friend of Herc’s, a stunning young woman who was a finalist for Miss Coahuila 2009. Playing well, it seems, has indeed won Herc some of the finer things in life.

The Azteca game was played on a Wednesday. I’ve arrived in Torreón on a Thursday, and Herc is scheduled to play for Santos on Saturday, which places him in serious relaxation mode most of the time I’m around. In season, as he recuperates between games, he usually chills at home, though he also likes to catch movies at the mall. We watch Total Recall when I’m there, and share tuna sashimi tostadas at this seafood place where the waitresses ask for his picture and he quietly points out to Ugo and me the narcos dining among us. (“You can always tell by the trucks they drive.”) He spends Friday night and Saturday afternoon sequestered in a Crowne Plaza hotel with his team. While he’s on lockdown, I drive around Torreón in the Audi. It’s a utilitarian city, to put it politely. Strip malls and stockyards and not much vegetation blocking the wind. Again: it’s hot. It’s dusty. I suspect Ugo is the only person ever to vacation here.

The game, on Saturday night, is at Estadio Santos Modelo, one of the most modern arenas in Mexico. It’s modeled after Pizza Hut Park in Dallas. The new stadium attracts a wealthier fan base, people more eager to be on the scene than to actually watch the game. In the twilight an hour before kickoff, cars have parked so far down the main road that Ugo and I watch women teeter for a half mile in stiletto heels, wobbling their way to the gates.

We postgame with teammates at a Torréon house party, an experience I’m not allowed to describe. (“Tonight the reporter’s hat comes off, Robert!”)

Tonight’s opponent is Pumas, a popular club. Pregame is all about Oribe Peralta, just back from London. The Olympic hero rides around the pitch on a John Deere maintenance cart, waving to the still-filling seats. At midfield he stands quietly as the scoreboard shows baby pictures and videotaped testimonials from his family. The theme song from Chariots of Fire animates the loudspeakers.

Oribe, naturally, gets the start. But so does Herc. He’d told me earlier that, for once, he actually didn’t want to start this game. The U.S. has a qualifier coming up in Jamaica. Herc, who is expecting a call-up — and he’ll get it — wants to be fresh for that game, which he feels is more important to his career. He lines up on the right side in a 4–2–3–1 formation, wide of the lone striker position he prefers, which goes to Mr. Gold Medal.

I sit in a green plastic seat next to Ugo, who helpfully explains all the ways the Pumas head coach is outfoxing Santos on the way to a oneand then a two-goal Pumas lead. (Santos eventually loses 2–1.) Flags of the countries where Santos’s players were born hang near the main scoreboard. In addition to the Mexican tricolor, there are flags for Panama and Colombia and Brazil and an American flag specifically raised to honor Herc. The setting sun reflects off the desert dust, giving the horizon an indigo glow. The air tastes like a communion wafer. I keep trying not to remember that this was the stadium where gunshots during a game prompted players to sprint to the locker room while fans dropped to the ground and pressed their children up against any available concrete surface.

Herc subs out early in the second half, Ugo convincing me he’d been misused tactically. That’s what it looked like to me, but I’m not the most qualified observer. I can’t always tell how good a player Herc is, really. I understand why a friend of mine who used to play professionally in Argentina says Herc “may be good enough for CONCACAF, but is he good enough for Brazil?” Herc works his ass off every outing. That’s obvious. But he’s not a standout talent. Following the 2010 World Cup, Herc waited so long for another call up to the national squad — almost two years — that he at one point changed his bio on Twitter to “former U.S. national team player.”

“Herc doesn’t have a lot of rope,” Frank Lemmon, his youth coach and still one of his best friends, tells me. “He’s not the kind of player who can play 20 caps, score four goals, and still make a roster. If he doesn’t produce every other game, he’s at risk of getting replaced.”

We postgame with teammates at a Torreón house party, an experience I’m not allowed to describe. (“Tonight the reporter’s hat comes off, Robert!”) There may have been streams of cerveza, whiskey, and tequila. A very attractive yoga instructor may have offered private lessons, inciting the jealousy of Miss Coahuila. Did we eat dozens of deliciously greasy tacos? Perhaps a full mariachi band wandered in at one point, and the sun may have been coming up when we got home, and Herc may have shouted out, “I work hard and I play hard!” I can’t say. I am free to share that sometime during the evening, when I asked Ugo about Herc’s appeal as a player, he told me this: “I think it’s where he came from. Everything Herc has he earned for himself.”

WHEN I GOT BACK TO MIAMI from Colorado in late 2009, only a couple thousand dollars remained in my bank account. As I priced apartments, I realized that for even modest, in-no-way-nice spaces, I didn’t have enough money to cover a deposit and the first month’s rent. As I considered my limited options, an idea that had once seemed pretty harebrained — move to Juárez, Mexico, the murder capital of the world — started to look not only more reasonable but, possibly, unavoidable. I didn’t have a book contract when I left Miami, or an agent or a proposal or any of that useful stuff. My relocation would be funded by Visa. But it was either go to Mexico or give up altogether. I went for it. My last shot.

I rented an apartment a couple miles south of the El Paso border and began building a life. I bought a cell phone. Workers hooked up my electricity and gas. Two men were shot dead outside my grocery store. I started hanging around the city’s soccer team, thinking the players and fans would reveal Juárez to me. I also thought, incorrectly, that I might be able to sell a magazine story or two about the team. “Soccer? Mexico? No thanks.” One month, even two months in, I couldn’t see how it was all going to work out. At night, when I lay in bed as sirens wailed up and down the streets around my apartment, I was often so worried — about my finances, about my future — that I couldn’t sleep. I was in deep.

I hadn’t followed Mexican soccer before I got down there. My exposure to La Primera was limited to what I’d caught while flipping through television channels back in the States. The quality of play surprised me. The team Chivas, for instance, had a guy named Javier Hernández, who sure looked to be world class. As I browsed the sports pages a couple months after my move, I saw that Hernández — Chicharito — shared the league lead in goals scored with… with… Herculez Gomez!

I asked a few questions about soccer in Mexico before getting to the matter I really wanted to address: had he heard from the national team? “Not yet,” Herc replied, “but they know where to find me.”

Just seeing the name gave me a jolt of adrenaline. I didn’t know he was down there. I thought he’d fallen out of the game, that his modest little career had ended. Yet there he was in Mexico, playing for the main team in Puebla and scoring so frequently he was in the running for the Golden Boot. I brought myself up to speed immediately.

Herc had seemed at home in Kansas City, at least initially. He started the final nine games of the 2008 season. Heading into 2009, management talked of a contract extension. But on the first day of physical testing for the new season, Herc tore his meniscus. Same right knee he’d injured in Colorado. Talk of a contract extension quieted down. Head coach Peter Vermes told Herc that even when he recovered, he’d be last on the totem pole of strikers, fifth or sixth in line for playing time. Vermes, Herc says, did not return his calls or the calls of his agent.

“It’s just one of those things where he didn’t see me as a viable option,” Herc explains. “Which would have been fine. I would have respected that. Not calling back a player? Not calling back an agent? Not giving a straight answer? I lost all respect.”

Into the off-season without a contract, Herc was left to exercise by himself at a 24 Hour Fitness. His savings dwindled. In late December of that year, 2009, Kansas City finally responded with an offer. It was less than half as much money as had been floated before the injury. Take it or leave it.

“He was crying after Kansas City,” his mother remembers. “He thought about giving up, but I told him that didn’t sound like him. He’s not a quitter. None of my kids are quitters.” Herc flew to Vegas for Christmas, then kept a promise to his girlfriend, flying on to San Francisco to join her for New Year’s Eve. Turning on his phone at the airport in California, he found messages about the only other professional option to develop: Puebla. Almost no money, and a short, one-season contract.

“My pride was hurt,” Herc recalls. “There was maybe $1,200 left to my name. I was like, this is a last-shot kind of deal.”

Not only did he play regularly for Puebla, but he was tied with Chicharito for the league lead in goals. It was thrilling to learn. It gave me energy. This was the spring of 2010. The buzz of his success had blown yet bigger by the time I made it to Puebla myself, toward the end of the season. The words “World Cup” started appearing in stories about him, which thrilled me, even just the speculation. He was hot — nine goals in nine games, not all of which he’d even started. When I approached him outside Puebla’s stadium, I tried to act professional, to disguise how excited I was at his success. I asked a few questions about soccer in Mexico before getting to the matter I really wanted to address: Had he heard from the national team?

“Not yet,” he replied. “But they know where to find me.”

That didn’t sound good. Hot as he was, Herc remained a very long shot. When the season ended, he flew to L.A. to train with Chivas USA, signaling to the national team that he was eager to keep playing. On television back in Juárez, I’d watch press conferences held after his practices, a growing number of reporters hovering around him, asking if he’d heard anything yet. He still hadn’t. “I’m just trying to stay in shape,” he’d say. When they named the 30-man roster for the initial camp, Herc made the provisional squad.

There would be one week in Princeton, New Jersey, then a friendly against the Czech Republic outside Hartford, the night before six final roster cuts. In the dressing room before the Czech game, Herc was handed jersey number 30 — the last guy on the team. He didn’t start, but when he subbed on in the second half, he headed a corner kick past Petr Cech and into the net.

I lost it. And I had been trying not to. My hopes, prior to that header, had been in check. All game long — all week long, actually — I’d been telling myself what an accomplishment it had been for Herc just to make the initial squad, how far he’d climbed in only a few months. But that goal slipped me into an electric haze, a place where I was barely aware of my limbs, or of the dog I was obligated to walk around my block, or of the sirens screaming across my violent city. He’s going to make the team! He’s going… to make… the team! I repeated those words two more times, then maybe ten more times after that. I was even more elated when he did survive the final cut, and then when I saw him standing on the sidelines against England, about to sub into a World Cup match, and then again when he made the field in the Slovenia game and when — get out of here! — he started against Algeria. But that night after the Czech friendly, before I knew anything for certain, I’d already been moved enough to write this in the journal that I keep: “Herculez Gomez is my hero.”

Admitting that should make me blush. It’s over the top for sure, possibly even embarrassing. But I’ll own it. In sports, heroes don’t have to be superstars. It’s just as possible — in fact, even more so — for an uncelebrated, often-injured, lifelong journeyman to transfer onto a fan the strength to keep going. Hang in there. It’s always darkest before the dawn. All the hoary maxims Herc scribbles on his whiteboard suddenly had a human face. Keep trying, believe in yourself, commit to a goal, and you might just taste glory.

I HEAR THAT ALL THE TIME,” Herc says just before I leave Torreón, after I tell him how he’s inspired me. “A lot of people share stories like that with me.”

When Herc made the World Cup team, Senator Harry Reid congratulated him on the floor of Congress: “Herculez exemplifies what can be accomplished with hard work, dedication, and passion.” Last spring, when Santos flew to Vegas for an exhibition against Real Madrid, hometown fans and the local media were more excited to talk to Herc than to Iker Casillas. There were newspaper profiles and TV features; a documentary cameraman followed him around. Mayor Oscar Goodman shook his hand. Another politician declared April 6 Herculez Gomez Day in Nevada.

“If you look at Herc’s career on paper now, you’d say, ‘Oh, that guy’s a blue-chip, pedigreed guy,’” says Frank Lemmon. “He was MVP of the Galaxy’s U.S. Open championship. He has two MLS championship rings. He played in the Club World Cup with Pachuca. He played in the FIFA World Cup in Africa. How many American players have their own foreign league championship? Or a Golden Boot?”

I caught Herc a couple more times in Miami, in camp with the U.S. team before the Jamaica series, and later again before the final two games that saw the Americans through to the Hex. Once more, Herc spoke with reporters, presented before even Clint Dempsey and Michael Bradley. It was Miami, yes, he speaks Spanish, yes, yes, but still. He’s the face of the U.S. men’s national team. After Herc addressed the press in general, he told me that everything in his life over the next two years is aimed at Brazil. His fitness, his plans in general — all are geared toward the World Cup.

“I’m making up for lost time at 30!” he said, his latest whiteboard mantra. When I asked if he feared being dropped from the national team before Brazil, he shook me off. Of course he’s concerned. He’s been dropped before, not that long ago. But by now he also has a record of pulling through, of pulling off the improbable.

“I’m like a fucking cockroach,” he said, laughing a little, using his hand to pantomime a steady climb. “I just keep going and going and going.”

I wouldn’t bet against him.