Why is one of the most talented players in American history sitting in a television studio when all he really wants is to coach a professional soccer team?

April 17, 2014

“First of all, in your defense, there’s no way that was a four-nothing game.”

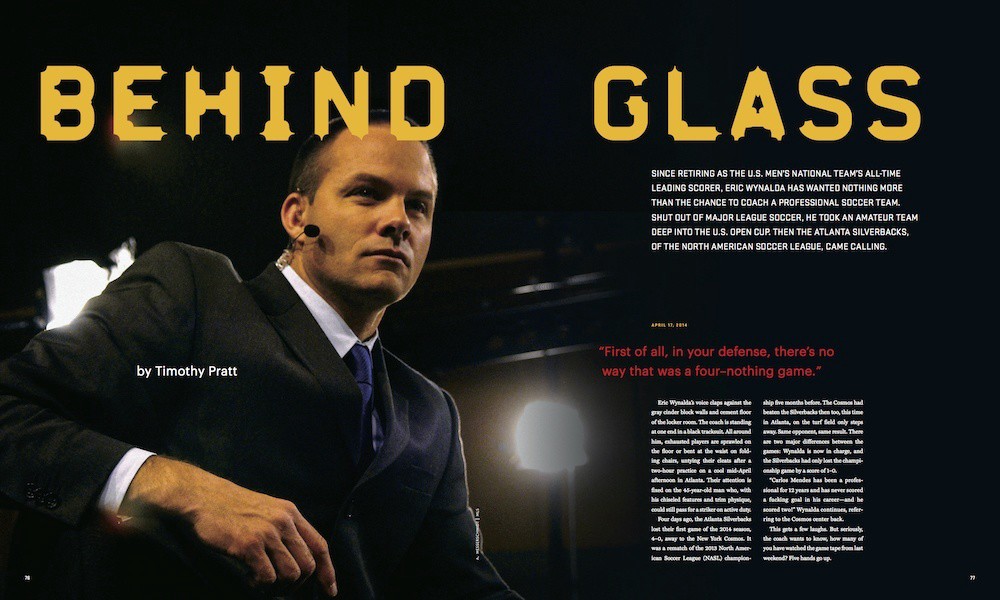

Eric Wynalda’s voice claps against the gray cinder block walls and cement floor of the locker room. The coach is standing at one end in a black tracksuit. All around him, exhausted players are sprawled on the floor or bent at the waist on folding chairs, untying their cleats after a two-hour practice on a cool mid-April afternoon in Atlanta. Their attention is fixed on the 45-year-old man who, with his chiseled features and trim physique, could still pass for a striker on active duty.

Four days ago, the Atlanta Silverbacks lost their first game of the 2014 season, 4–0, away to the New York Cosmos. It was a rematch of the 2013 North American Soccer League (NASL) championship five months before. The Cosmos had beaten the Silverbacks then, too, this time in Atlanta, on the turf field only steps away. Same opponent, same result. There are two major differences between the games: Wynalda is now in charge, and the Silverbacks had only lost the championship game by a score of 1–0.

“Carlos Mendes has been a professional for 12 years and has never scored a fucking goal in his career — and he scored two!” Wynalda continues, referring to the Cosmos center back.

This gets a few laughs. But seriously, the coach wants to know, how many of you watched the game tape from last weekend? Five hands go up.

He wants to talk about the 38th minute, the corner kick that dropped to Mendes’s right foot in front of goal. Left completely unmarked, Mendes slotted home his second of the evening and the Cosmos’ third. The Silverbacks had defended zonally instead of man-to-man. “That was my mistake,” Wynalda says. “As far as anything I’ve been taught in my career, it’s worth repeating that it’s better to tuck in and then attack the ball [when defending a corner] than stand facing the ball, waiting.”

He wants to talk about defense. The Silverbacks made it to the previous championship game playing a 4–2–3–1 formation. “That was so fucking boring,” Wynalda says. “That was José Mourinho.” The coach wants his team to play a 4–3–3, sometimes a 3–5–2 — setups that express the offensive mentality that once made him a force for the U.S. men’s national team — but that’s going to take more time. “We’re just not there yet,” he concludes. “Let’s go back to the boring shit we did last year.”

Wynalda steps to his left, uncaps a black Magic Marker, and draws four Xs in a line and two more above those. He traces a square connecting the two middle Xs of the back four to the two defensive midfield Xs above them. “I hated it when the center backs would be behind me, pushing me out. Germany, Holland, Belgium — they all had these big guys. The job of the two guys in front of the center backs is to make life impossible for the other team.”

Marcos Senna, the former Spain international, did that for the Cosmos, chattering away before set pieces to distract his Silverbacks opponents. “You have to focus on your job,” Wynalda says.

“It didn’t look like a 4–0,” he repeats at the end of the session, “but it’s the little things that matter. I apologize for the day. I told you it was going to be a long one.”

Music comes on and the players strip down and head for the showers. Wynalda beckons me out of the locker room and down the tunnel that leads under the stands into the parking lot of Atlanta Silverbacks Park. It’s our first one-on-one meeting since I’d requested access to the team three months earlier, when Wynalda was announced as the new coach. He’d be splitting time between Southern California, where he’d continue to work as a TV commentator, and north Georgia, where he’d take his first crack at coaching a professional soccer team. “Sure!” he says when I thank him for agreeing to let me tail him over the next few months. “I’m an open book!”

Wynalda says he knows a good Cuban place and gets behind the wheel. He says he couldn’t sleep for two days after losing the Cosmos game. “I feel responsible,” he says, for using the wrong formation and overlooking the team’s defensive vulnerabilities. “It’s like the general who led 20 soldiers to death — he must feel a guilt complex.”

Wynalda’s mind ranges in conversation, but it always comes back to soccer. He’s as likely to comment on a World Cup game from twenty years ago as he is on the game he just coached, if it touches on a topic that interests him. He has a swagger, and plenty of opinions, but he never tries to bully you into believing so much as make a convincing case for whatever he’s talking about, and he draws on quotes from thinkers as diverse as Bear Bryant and Ralph Waldo Emerson to make his points.

On the way to the restaurant, he uses a line from the Alabama football coach to explain his approach with the team after the loss: “If anything goes bad, I did it. If anything goes semigood, we did it. If anything goes really good, then you did it. That’s all it takes to get people to win football games for you.”

Winning games is Wynalda’s reason for being in Atlanta, and yet there is so much more at stake for him here. He is one of the most decorated players in the history of American soccer. Wynalda was the first of his countrymen to play in the German Bundesliga, where he was named Newcomer of the Year in 1992–93. He scored a crucial goal — a perfect, curling free kick to the upper-left corner against Switzerland — without which the U.S. would not have progressed out of the group stage at the 1994 World Cup. Two years later, Wynalda scored the first goal in the first game in Major League Soccer history. He retired from international soccer in 2000 as the U.S. men’s all-time leading goal scorer, with 34 strikes. (That record has since been eclipsed by Landon Donovan; Wynalda is now third.) But since retiring from professional soccer altogether in 2001, Wynalda has been unable to find work as a professional coach, even as many former American players none of whom reached Wynalda’s heights on the field, have gotten their chances on the sidelines in MLS. Wynalda wants to win in Atlanta, sure, but if you know his story, you know that winning here is basically a necessary stepping stone to achieving his ultimate aim: proving he deserves a chance to coach a Major League Soccer team.

Alexi Lalas met Eric Wynalda in a hot tub. It was nearly a quarter century ago, in 1991, and Lalas, a senior at Rutgers, had been called up to the U.S. men’s national team for the first time. Wynalda had been on the squad for a year. “Eric brought a couple beers over,” and joined him in the tub, where he was soaking after a training session. They’d eventually become roommates, from 1994 until 1998. “He had incredible energy,” Lalas says. “He wanted to have fun on and off the field. There was a gleam in his eye.”

That gleam is familiar to anyone who has seen one of Wynalda’s broadcasts. His face is still boyish, and he still comes across as a merry prankster, someone who delights in playing the contrarian, the provocateur.

“He believed in himself,” Lalas says. “He had a beautiful arrogance that all of us who have been successful have to have.”

After retiring from the game, Lalas served as general manager for three MLS teams, including the LA Galaxy. Wynalda hasn’t worked for the league since stepping off the field, making a living primarily as a pundit, first for ESPN and now Fox. He has long expressed his desire to coach at a higher level and his frustration over not getting a chance. In 2010, he lobbied unsuccessfully for the head coaching job at Chivas USA. He has described himself as an outcast, a man blackballed by MLS and the U.S. Soccer Federation for speaking his mind.

“He’s gotten himself in trouble for certain things he’s said,” Lalas says, referring to Wynalda’s public criticism of all aspects of the American game — and the people who run it — on Twitter (which Wynalda quit in January 2012) and other public forums. Wynalda expresses his opinions about everything from youth soccer (too organized, not enough free play) to MLS (not enough coaches with high-level experience) to the national team (not enough risk taking). “In certain corners of MLS, he’s a pariah. I think he’s aware it’s of his own making.”

Lalas recalls that, as a player, Wynalda was aware of the importance of managing a public image, even though relatively few people were paying attention. “There was definitely an understanding: your job as a U.S. Soccer team player goes beyond what happens on the field,” Lalas says now. “Eric would say, ‘You can be crazy, you can be a person — but you have to recognize that you’re also an ambassador, a pioneer.’”

And yet of all the players from that pioneering generation, it’s Wynalda who remains on TV, offering his opinions about what happens out on the field, while harboring a desire to be on the sidelines, influencing games himself. The overriding theme of Wynalda’s post-playing career has been his inability to catch a break doing the one thing he really wants: coaching a professional soccer team.

The thing is, Wynalda can coach. Pablo Cruz and Mike Randolph both know it. They’re two of Wynalda’s starters for the Silverbacks, but they’ve played for him before. In 2012, Wynalda began his first stint as a head coach when he took over Cal FC, an amateur side based in Ventura County, California. Small teams like Cal FC usually lose in the early rounds of the Open Cup, but Wynalda’s band of part-timers won a couple of games and found themselves in the fourth round, playing away against the heavily favored Portland Timbers.

Four years earlier, Cruz had been playing for the U.S. U-17 national team, but when Wynalda recruited him for Cal FC, the California-born son of Honduran immigrants was 20 years old, out of the game, painting houses with his father. The five-six midfielder has good vision and makes smart passes. He credits Wynalda with making him more aggressive.

“He gave me confidence since I first met him,” Cruz says of Wynalda. “He told me, ‘Go at ’em.’ I used to not do it. I didn’t want to lose the ball.… He put in my head, ‘You can do it.’”

“Try and slice up the other team,” Wynalda recalls telling Cruz. “Take a risk!’”

Mike Randolph was a stocky, speedy left back trying to catch on with the LA Galaxy, for whom he played in 39 matches between 2006 and 2008, when Wynalda approached him after a match to tell him he liked the way he got forward out of defense. “I wanted to tell him I was a fan, but couldn’t get in a word edgewise,” Randolph recalls.

By 2012, he was working at a women’s clothing store in Santa Ana, California. He wanted to get into youth coaching, but Wynalda got in touch with a different opportunity. “I’ve got a team,” he said, “and want to make a run at the Open Cup.”

Cal FC played in the U.S. Adult Soccer Association, the nation’s fifth division. By the time they made it to the fourth round of the U.S. Open Cup, drawing the Portland Timbers in May 2012, Wynalda had been training his squad for just four months.

No team from the association had scored against a team from MLS in five previous Open Cup meetings. Randolph says he and his teammates were clearly less fit than the Timbers, “but we were very good with the ball.” Still, by halftime in Portland, his legs were giving out. The game remained goalless. Wynalda gave “one of the calmest speeches I’ve ever heard,” Randolph recalls, convincing his players that they were still in the game.

In the second half, Portland kept attacking, kept pressing, and kept finding Cal FC’s beleaguered defense impossible to unlock. The game was still goalless at the end of regulation time. In the 95th minute, Cal FC striker Artur Aghasyan, who had been cut by Real Salt Lake and Chivas USA, scored on a breakaway. Cal FC had eight shots on the night; the Timbers took 37. But at the end of extra time, the scoreboard in Portland read “Cal FC 1, Timbers 0.”

Cal FC would go on to lose in the next round against the Seattle Sounders, the cup’s defending champion and eventual runner-up, but the team had made history with its defeat of Portland.

Andy Smith had been paying attention. The Silverbacks GM was watching from Atlanta, where his team had won just one of its previous 13 games by the third week of June. Smith was looking to make a change.

“He had just done something incredible with a bunch of amateurs,” Smith says. He got Wynalda’s phone number from Rob Stone, a friend of Smith’s and Wynalda’s on-air colleague at Fox. “I just cold-called him,” Smith says. “I didn’t expect to get an answer.” Wynalda answered from his car. It was June 23rd and he was picking his way through Los Angeles traffic to catch a flight to Miami for one of Lionel Messi’s benefit matches.

“Look, you’ve been saying you want to coach,” said Smith, a former ticket sales executive with the Colorado Rapids, D.C. United, and FC Dallas of Major League Soccer. “Nobody’s given you a chance.”

Over the course of their 45-minute conversation, Smith offered Wynalda a chance. Wynalda turned it down. He didn’t want to leave his work with Fox, or disrupt life for his four kids.

Five hours later, Smith’s phone rang. Wynalda had landed in Miami.

“I thought about it,” he said. “I want to do it.”

Wynalda hadn’t completely overcome his hesitation. He agreed to spend six weeks with the team in July and August as an interim coach and then stay on as an adviser. During Wynalda’s 13-game interim stretch, the Silverbacks won and tied more games than they lost. Wynalda’s role as adviser included identifying players; the team signed Cal FC standouts Randolph and Cruz, as well as forward Danny Barrera, within weeks of his arrival.

One day, he was walking into the locker room as Ricardo Montoya, the coach of the reserves, was walking out. Montoya introduced himself, and Wynalda asked if two of the reserves he’d been tracking — Chris Klute and Jahbari Willis — were ready to join the first team.

“They were ready a long time ago,” Montoya said, recalling later that “it was the first time in two years that someone had asked my opinion.” The men spoke some more, and within several weeks, Montoya had become Wynalda’s assistant coach with the first team.

Brian Haynes, Wynalda’s successor, would lead the team to first place in the 2013 spring season, earning Atlanta the right to host the league’s championship game against the winner of the fall season. That competition didn’t go nearly as well; the Silverbacks finished in the middle of the table and Montoya left the team over differences with Haynes.

In the championship game on November 9, the Silverbacks lost to the Cosmos before a home crowd of 7,211.

After the lackluster fall season, Smith decided to part ways with Haynes and once again found himself looking for a head coach. He and Boris Jerkunica, one of the team’s owners, agreed that they “wanted to work in a system like Wynalda’s — a more attacking style,” says Smith. “Boris said, ‘What about Eric?’”

They met Wynalda for dinner at the Tilted Kilt in Atlanta a few days before the new year, and Boris laid out a new proposal: Wynalda would come to Atlanta for three or four days each week and oversee some training sessions and the weekend’s games. A regimen of red-eye flights would ensure that he could be back in Los Angeles to meet his his commitments with Fox. Technically, the team would be eliminating the position of head coach, and Wynalda would assume those duties under his title of technical director.

It wasn’t ideal, but as Wynalda told Smith over a scotch and amaretto afterward, “If he’s crazy enough to think it, maybe I’m crazy enough to do it.”

The agreement, which Smith says has never included a contract, was sealed with a handshake. “It wasn’t a business deal,” he says. “It was a passion play.”

May 3, 2014

It’s a beautiful day in Atlanta. Players laugh when free kicks sail over the crossbar at the end of the training session. The coach puts a few on frame as well. After the loss to the Cosmos and a 2–1 loss to the San Antonio Scorpions in the home opener, the Silverbacks traveled to Tampa and got a 3–1 win. That was six days ago, but spirits remain high ahead of tomorrow’s home match against the Ottawa Fury.

“It’s nice to win,” Wynalda says after practice. Caribbean tunes filter through the door that separates the locker room from his office. “In the last game, we were better.” He gave the players two days off at the beginning of the week. Wynalda has a surprisingly optimistic way of thinking about the goals they’re conceding. “We haven’t been beaten by a good play yet,” he says. “We’ve been scored on by seven mistakes.”

In other words, the problems are fixable for someone with Wynalda’s experience.

“It’s the same game, whether a Sunday league or the Champions League — just at a different speed or different skill level,” he says. “I guess the advantage I have is I know what it’s supposed to look like from close-up. Ninety percent of the people in this country don’t. I’ve been extremely fortunate. I’m not bragging. It’s just that a lot of people can see a play and say it’s a good play, they just can’t say why. I can.”

He hasn’t been home in over a week, except for about 12 hours after the Tampa game the previous Sunday. He’d flown back to L.A., touching down on Sunday afternoon, then returned to the airport before dawn on Monday morning to catch a flight to Munich that connected back through Atlanta. Rather than broadcast from a studio in Los Angeles, Fox had decided to send their onair talent to Europe for some of the later stages of the Champions League, and it was complicating Wynalda’s already complicated schedule.

The coach is tired but his mood is, in his words, one of “cautious optimism.”

The following day, Wynalda’s optimism is rewarded. The Silverbacks beat Ottawa 2–1, which gives them two wins and two losses on the young season. Both of Atlanta’s goals came in the first half. The Canadian team got its lone goal in the 90th minute, which means that Wynalda’s team went almost an entire match before making its eighth mistake of the season.

June 6, 2014

On the first Friday night in June, less than a week before the opening game of the World Cup, an Atlanta pub called the Elder Tree is filling up with soccer fans. All dark wood tables and paneling with a tin ceiling, the pub affects a European atmosphere and is friendly to soccer, with scarves from the world’s teams tacked to the walls.

Already a few drinks into the night, Wynalda begins the Q&A session by telling the 40-something people present to keep everything he says “off the record.” The topic is supposed to be the World Cup, but given Wynalda’s personality, no question is out of bounds. He repeats many of his criticisms of the state of soccer that he has already said on the record, or will state publicly in the coming months, like when he calls USMNT head coach Jurgen Klinsmann an “egomaniac.”

Wynalda enjoys playing the enfant terrible. In 2012, he wondered on Twitter how Portland Timbers owner Merritt Paulson could sideline Colombian player José Adolfo Valencia for surgery immediately after signing him. The Timbers owner, who has his own reputation for saying what he actually thinks on Twitter, shot back: “I will explain it to you if you can learn to read before tweeting first. Seriously, you are a frickin Twitter trainwreck… Every time you tweet it’s a press conference.”

Last year, Wynalda criticized former USMNT Coach Bob Bradley for his lack of playing experience at a high level. During the most recent World Cup, he blasted Jurgen Klinsmann for not being aggressive enough in his approach and for being “un-American” in his attitude. He wrote a piece for the magazine put out by Georgia Soccer, the state’s governing youth soccer association, advising parents to “zip it” on the sidelines while watching their children play. In the same piece, he recalled going to one of his children’s U-6 games with a video camera. When he watched the tape afterward, he could hear another father yelling “shoot” at his 7-year-old son on the next field during a game — 314 times!

This is the behavior Lalas is referring to when he says Wynalda makes for “good copy.” “You wonder, What did Eric say today? Who’s he fighting with? He can ruffle feathers with the best of them.”

The event at the Elder Tree is taking place the night before the last game of the spring season, at home against the expansion Indy Eleven. That two-and-two record after the Ottawa game was the closest they’d come to a positive winning percentage all season. The Silverbacks have played four more league matches, winning just one of them, and Wynalda missed it because he was in Lisbon to call the Champions League final.

In May, Lalas tweeted that Wynalda was “shortchanging” Atlanta fans. Wynalda was upset. He called Lalas about the tweet — Lalas says they worked it out — and told me his former roommate had been guilty of “bad journalism.”

Still, “I kept coming into the [Silverbacks] office and saying, ‘There’s another curveball,’” he remembers. Montoya would later tell me that he and Wynalda had discussed the head coach’s possible exit as early as May as well.

The spring season has been tough. Tomorrow, the Silverbacks will draw with the Indy Eleven 3–3. This time last year, the Silverbacks had locked up home field advantage in the league final. This year, the point from the draw puts them eighth in the 10-team league (their 10 points are even with the teams in the sixth and seventh places).

But tonight, at the Elder Tree, Wynalda gives a show of optimism. After the Q&A session, he hangs out at the bar with Smith. “The last time I coached with a hangover,” he says, raising a glass of scotch, “we beat Tampa Bay 3–1!”

June 24, 2014

The first half of the NASL season hadn’t gone well, but there was still the U.S. Open Cup. “It all started with the Open Cup,”

Smith says — meaning Wynalda’s performance in the competition is what put him on the Silverbacks’ radar in the first place. He knew the tournament was important to Wynalda, perhaps a last chance to show what he was capable of achieving with Atlanta — and against the best teams in the United States.

The tournament is structured so that NASL teams enter in the third round, MLS teams in the fourth, after the stronger small clubs have knocked the weaker ones out of the competition. On May 27, the Silverbacks had beaten the NPSL’s Chattanooga FC 5–0, setting up a fourth-round matchup against Real Salt Lake.

Soon after the event at the Elder Tree, Smith had a talk with his coach. “I could tell it was a strain,” he recalls. “I told him, ‘I know what you’re thinking. I’m going to assume you want to see what’s going to happen in the Open Cup before you make a decision…’ I told him he should go out on his own terms.”

On June 14, Atlanta hosted Real Salt Lake, who would finish the MLS season third in the Western Conference. The teams had drawn each other in the third round of the 2013 tournament, and Salt Lake, playing at home, had beaten Atlanta 3–2 in overtime. This time was different. Salt Lake went ahead in the 10th minute, but the Silverbacks tied the score in the 33rd, then got a 90th-minute winner to upset the visitors. Wynalda now had a 2–1 record against MLS teams in the Open Cup, and the victory gave him a chance to beat another one, ten days later, in Colorado.

June 24 is a Tuesday, outside of Wynalda’s usual time with his team, and the head coach arrives in Denver just in time for the game. The Rapids have won six league matches by this point in their season — the same number as Salt Lake when Atlanta had beaten the Utah club less than two weeks earlier.

This time, the Silverbacks get the first goal. In the 22nd minute, midfielder Junior Burgos lobs a ball to forward Jaime Chavez, who brings it down with his chest as he runs into the box. Colorado goalkeeper Clint Irwin comes to meet him, but Chavez, who in an effort to control the ball has contorted his body to face away from the goal, dinks the ball over his own head and beyond Irwin’s reach into the Rapids’ net.

Minutes later, rain, sleet, and lightning force a delay of nearly an hour, and when play resumes, fewer than 2,000 fans remain in the stands at Dick’s Sporting Goods Park. Chavez strikes again with a soaring header in the 58th minute, and it looks like Wynalda is set to burnish his reputation for taking down MLS clubs in the Open Cup.

Five minutes later, things begin to unravel. Chavez tangles with Colorado captain Drew Moor as they chase a through ball. Both fall to the ground, and as Chavez gets up, he steps on Moor’s face. Irwin and Rapids defender Marc Burch confront Chavez, and as players on both sides begin to jostle, Wynalda and Montoya step onto the field. In the next five minutes, referee Juan Guzman tries to clean up the mess. The referee, who hasn’t so much as cautioned a single player to this point, ejects seven men: Burch from the Rapids and Chavez along with two other Silverbacks, plus Wynalda, Montoya, and Rapids head coach Pablo Mastroeni. As Wynalda stalks off the field in a huff, a lone Colorado fan baits him into a shouting match.

For the remaining half hour, Atlanta defends with their eight men against Colorado’s 10. The Rapids score in the 75th minute but the Silverbacks hang on for the win. Wynalda now has four wins and one loss against MLS teams in the Open Cup, and the victory gives him a chance to go for a fifth, on July 9, at home against the Chicago Fire.

Well, technically. Wynalda is suspended for the match, and Atlanta is missing the three starters who were sent off against Colorado. The match is another chippy affair. Both teams are playing with 10 men by the 31st minute, when Atlanta’s Jesus Gonzalez and Chicago’s Mike Magee — the reigning MLS MVP — are shown straight red cards for fighting. Atlanta enjoys more possession but Chicago gets more shots on target. The match is tied at zero and then at one for much of the game, but the Fire score on a penalty kick in the 82nd minute and add another three minutes later. Atlanta is out of the tournament.

Wynalda has been watching from the press box with Smith. After the third goal, Smith recalls, “things got real quiet.”

July 19, 2014

On an unusually cool July evening in Atlanta, Eric Wynalda is about to take his place on the bench as coach of the Silverbacks for the last time. It has been six months since they launched the experiment, since Wynalda began his exhausting weekly commute across the continent as he tried to to build his coaching career.

“This has taken a toll on me — the stress of the lack of results,” he tells me over the phone on the drive from his hotel to Silverbacks Park. “The confident, arrogant side of me is a little frustrated.”

His team had been the underdog in the match against Chicago, and yet Wynalda calls the loss “a hit to our overall psyche.” A few days afterward, he and Smith had spoken on the phone. After the disappointment of the spring season, they’d decided not to make any decisions about the coach’s future until after their run in the Open Cup had ended. Now it was over.

“Should we call it a day?” Smith had asked. Yes, Wynalda said. The two men agreed that the project had reached its end. Wynalda would stay on as an adviser, but day-to-day coaching duties would be taken over by Jason Smith (no relation). It’s the first time he has ever quit anything, Wynalda tells me on the phone. He mentions a pool back home in Southern California, “where apparently there will be a drink waiting for me.”

But there’s one more game to coach, and Wynalda desperately wants to beat FC Edmonton. The Silverbacks have already lost their first match of the fall season, 2–1 to Tampa Bay, three days after the loss to Chicago.

It’s a close game, and physical, with Edmonton in the book for a foul minutes before the halftime whistle. Atlanta goalkeeper Joe Nasco, on loan from the Rapids, is drawn off his line three times to bat away shots, but the half ends without a goal.

At the break, Wynalda decides to take out two of his starters, Junior Sandoval and Junior Burgos, both among the team’s top scorers. “It was not the game for them,” he says afterward. “They were trying to play soccer against a team playing rugby.”

His assistants suggest substituting Pablo Cruz, but Wynalda leaves him on the field. It is such a physical game that he has a hunch it could be decided on a free kick, and Cruz is effective on set pieces. Cruz has flourished in Atlanta, repaying Wynalda’s belief in him. He will finish the season as the team leader in assists and third in goals.

The game remains scoreless in the 75th minute. Four Edmonton players have been cautioned. Silverbacks midfielder Kwadwo Poku draws a foul about 20 yards out, and Edmonton is booked a fifth time. Cruz grabs the ball.

Cruz sets the ball and takes a few steps back. “I bet my mortgage he scores,” Wynalda says to the Silverbacks trainer. The wall is set. The referee blows his whistle. Cruz begins his run toward the ball and curls it over the wall and into the upper-right corner of the goal.

“I wanted to cry,” Wynalda says afterward. “I knew he could win the game for us. It was probably the perfect way for me to go out, with him winning the game for us.” The postgame locker room is not that of a winning team — it’s quiet, subdued. Wynalda knows he won’t be in the room again, at least not after leading this team through a game. “There wasn’t any jumping up and down,” Wynalda recalls. “It was a surreal moment.”

He sees Mike Randolph, whom Wynalda brought with him from Cal FC, and who has become Atlanta’s captain. They shake hands. Randolph nods and says, “Thank you, coach.”

“Thank you, captain,” Wynalda says.

In the days to come, Wynalda doesn’t return my calls or text messages. It’s the first time I’ve been unable to reach him.

I find Smith in the bleachers at Silverbacks Park, in the shade of a light post where he usually sits when the Atlanta sun is hot.

“Maybe I drank the Kool-Aid,” Smith says. “What surprised me is that a guy like Eric Wynalda would do what he did — be on an airplane every week, sometimes from Europe. That he would be willing to fly this far, and lose — and keep getting on a plane. That surprised me on a human level.… If he had been available full-time, I have no doubt the results would have been different.”

The man who brought Eric Wynalda to Atlanta still thinks he should get an opportunity to coach at the highest level in this country. “The players that he brought in — some of them were washing dishes when he found them.… He’s given a lot of people a chance, and yet his phone isn’t ringing.”

It’s the tragic irony of Wynalda’s story. When he finally got his shot, he didn’t fully take it. Sure, he’s still got a very impressive winning record against MLS teams in the Open Cup, but his record in Atlanta won’t make him irresistible to the next executive who might be willing to try something novel.

“He gets in his own way,” Smith says, “and too many clubs play it safe. They’re under a lot of scrutiny and there’s a risk involved with Eric.”

When I finally get Wynalda on the phone from Los Angeles, he still sounds drained, somehow vulnerable. He’s driving, as he often is when we talk. “For lack of a better word, I was sad,” he says. “It was hard to give up coaching after all that.”

The dream, it seems, is even harder to relinquish.

“A guy like me can only stay on the other side of the glass for so long. That competitive part of me is alive and well. I want to be involved in the game, not commenting on it.”

Note: When Wynalda ended his coaching duties in July, the Atlanta Silverbacks announced that he would stay on as technical director. Then two events occurred: on December 2, the Silverbacks announced that the NASL would take over the team while a local ownership group was sought. Two days later, the team announced that Wynalda would no longer continue in his role as technical director. “We understand his desire to stay closer to his family, and want to once again recognize his commitment to our club for the past three seasons,” said Andy Smith in a statement. Then, on December 23, the club announced that Gary Smith [no relation] would become the new head coach. Smith, from England, previously coached the Colorado Rapids for two years, leading them to the MLS Cup in 2010.

Timothy Pratt is a writer who lives in Atlanta. He tweets from the handle @TimothyJPratt.