“MLS 2.0” has ushered in an era of unprecedented success, but it may have run its course

By Richard Whittall

Four years ago, Major League Soccer commissioner Don Garber mused on the ways his league had changed since its founding in 1996. Following a rocky first decade during which MLS survived financial loss, contraction, and an antitrust suit from the players that was settled in the league’s favor in 2002, he told the website Big Apple Soccer that MLS entered a phase he called “MLS 2.0.” The change began in 2005, with the addition of Chivas USA and Real Salt Lake, the league’s 10-year deal with Adidas, “and then really got legs in 2007 with David [Beckham] coming into the league and a number of new stadiums, obviously more expansion, and new television contracts.”

Eight years after Beckham’s arrival, it’s safe to say that MLS 2.0 has been a success. The league is now home to 20 clubs — seven more than in 2007 — with Atlanta set to join in 2017 and Minnesota and another Los Angeles franchise signing on for 2018. Fourteen of the current teams play in stadiums built for soccer, a number that will grow after Orlando City moves into its new home in 2016 and D.C. United completes construction of its long-awaited arena on Buzzard Point in 2018.

And while MLS is still a single-entity league with tight controls on club spending, since 2007 it has reaped the benefits of the “Beckham rule,” or “designated player rule,” which allows teams to pay up to three marketable stars above the centrally allocated maximum roster budget. This has led to an influx of expensive, older European club stars like David Villa, Frank Lampard, Steven Gerrard, Didier Drogba, Kaká, and Andrea Pirlo. The league has received its share of “retirement home” jibes, but the trend toward using the DP slots for older stars may be changing. This year Toronto FC signed the 28-year-old Italian midfielder Sebastian Giovinco, a player very much in his prime, and the LA Galaxy acquired 26-year-old Mexican international Giovani dos Santos.

Despite its reliance on star power to attract fans, the league hasn’t abandoned its focus on player development, and in 2013 it partnered with the third-tier United Soccer League (USL) to allow MLS clubs to field reserve teams against lower-league competitors. Meanwhile some clubs, notably Sporting KC and Los Angeles, have opted to use their DP slots on domestic talent such as Graham Zusi, Matt Besler, and Omar Gonzalez. Toronto, meanwhile, used theirs to sign Michael Bradley and Jozy Altidore.

In a world where TV rights fuel the pro sports industry, MLS’s failure to significantly increase its ratings could lead to stagnation.

All of these changes have arguably improved the on-field product during the last decade, and MLS continues to draw fans in good numbers — 2014 set an all-time average attendance record of 19,149 per game, and as of the end of July 2015, the league average had topped 21,100. The league has also flexed its muscle in the television-rights game. MLS is currently in year two of a reported $90 million, eight-year deal struck with ESPN, Fox, and Univision, and this past spring the league reached an agreement with Sky Sports to broadcast matches in the U.K.

With all of this positive growth, it’s perhaps unsurprising that Garber felt emboldened enough in 2013 to say MLS would aim to be among the best soccer leagues in the world by 2022. And while it may be tempting to claim we’re now in “MLS 3.0,” the truth is, the league’s decade-old strategy for expansion remains fundamentally unchanged. Despite MLS’s reach into new markets and its growing heft as a salable TV property, the league refuses to radically alter its single-entity business model or significantly expand its player budgets in order to help grow revenues further. We’re still very much in MLS 2.0.

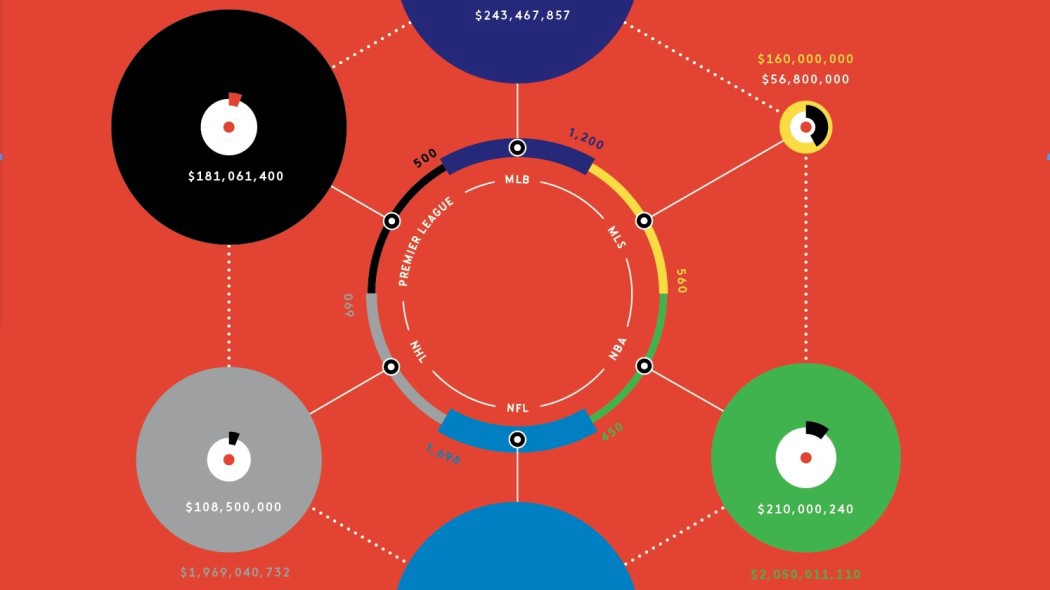

One result of the league’s selective spending policies is an astonishing level of income disparity. The vast majority of MLS players get a fraction of the salaries afforded to designated players. The collective bargaining agreement reached earlier this year pushed the league’s minimum salary to $50,000, but, as Aaron Gordon pointed out in an article for Vice this past summer, “the top 10 players make a whopping 35.5 percent of the total MLS salary base.” And the rising cost of DP salaries hasn’t done much to increase wages at the bottom — the league’s median salary is $110,000, compared to $770,000 in the NFL and $987,500 in MLB.

MLS owner/investors enjoy what is still a relatively low professional sports wage bill — as of 2015, the maximum allowable budget for MLS clubs was $3.49 million. It may be that, despite its commercial and broadcast deals and hefty expansion fees for new clubs (New York City FC reportedly paid $100 million), those in charge simply don’t think that spending more on players would result in revenue growth. Garber claimed in July 2015 that the league was still in “investment mode,” and last year, MLS president Mark Abbott said that the league still loses $100 million annually.

The reason for the lack of funds may be related to the one crucial area where MLS has failed to make significant gains since 2005 — TV ratings. MLS has long had to wheel and deal to get its product on the air in a crowded live sports environment. After Garber took over as commissioner in 1999, the league made significant inroads in the broadcasting game — including its masterstroke acquisition of the English-language TV rights to the 2002 and 2006 World Cups via its marketing enterprise, Soccer United Marketing. This not only allowed MLS to earn money from an ad revenue–sharing agreement with ABC/ESPN, but it also gave it a vital bargaining chip in its bid to land a lucrative broadcasting deal of its own.

In 2005, for example, SUM declined to make a move for the 2010 and 2014 World Cup rights, instead opting to help support ABC/ESPN’s bid in return for a future TV deal for MLS, which the league eventually struck with ESPN in 2006.

Yet while MLS’s quid pro quo strategy worked well to get its foot in the door, it hasn’t led to major audience growth. Television ratings for MLS are very poor. As Leander Schaerlaeckens noted in a sobering article for Yahoo! Sports in January 2015, “ESPN’s MLS national broadcast ratings have hovered between 220,000 and 311,000” over the last decade or so. These are paltry numbers compared not only to sports like Major League Baseball and the NFL, but also the Premier League, which airs unchallenged in the morning time slot in the U.S. While MLS TV ratings have risen slightly during the 2015 season, which has featured more big-name stars than ever before, Schaerlaeckens’s warning about the league’s current DP strategy still holds merit: “Star power alone, rented from the big names brought over throughout the years, doesn’t get people to turn on their TVs consistently or sustainably.”

This is not a small problem; if MLS is to crawl out of “investment mode,” the league will need to attract continuously bigger and better television deals. There’s no clear-cut path to that objective, but loosening the league’s financial strictures to attract higher-quality players in the rank and file — not just marquee-name exceptions — seems like a logical next step. Because in a world where television rights fuel the professional sports industry, MLS’s failure to significantly increase its ratings could lead to stagnation, or worse.

The league, now three years older than the original North American Soccer League was when it folded in 1984, has long prided itself on its low-cost, risk-averse growth strategy. Soon, though, it may have to gamble in order to create a path forward. We haven’t reached the real MLS 3.0 yet. Getting there may be scarier, but potentially more exciting, than any previous period in the league’s history.

Follow Richard Whittall on Twitter at @RWhittall.