Don’t believe the hypothetical: “What if America’s best athletes played soccer?” is a dumb question for a variety of reasons

Last August, midway through Landon Donovan’s appearance on The Dan Patrick Show, the host asked him a question that American soccer players, coaches, and fans have been hearing, in one form or another, since the U.S. men’s national team wore short shorts and mullets: “If I took the best athletes in our country, and they started with soccer, would we be the best soccer team in the world?”

While Donovan patiently indulged the question, I leaked a sigh like a ruptured steam pipe. About a half dozen possible responses jostled for space in my head. For one thing, the question implies that American soccer isn’t attracting elite athletes, which is not true and hasn’t been for some time. For another, it ignores the many other factors that go into producing an elite national team.

Patrick’s inquiry is misguided, but at least it’s misguided in interesting ways. Answering it requires us to think about the state of soccer in this country versus the rest of the world, about the ways that mainstream sports figures perceive and misperceive the game as it emerges here, and — if we pull the lens back a bit — about the nature of athleticism itself.

Armed with these and other questions, I went looking for answers in the American soccer community and beyond. The insights I gathered were both practical and philosophical, and imparted a keener sense of just how far the U.S. has to go to achieve its goals as a soccer nation.

Patrick’s question assumes that American soccer players aren’t elite athletes, but this hasn’t been true since at least 1999, when the speedy Donovan and the ultraquick DaMarcus Beasley took the Golden and Silver Balls, respectively, at the U-17 World Cup. Since then, players like Jozy Altidore, Geoff Cameron, DeAndre Yedlin, and Brek Shea, to name just a few, have provided a steady stream of quality athletes for the American game.

“Just because you’re a great athlete doesn’t mean you’re going to transform yourself into a great soccer player,” says Dominic Kinnear. “If that were the case, then maybe Jamaica would win a World Cup faster than America. Right?”

Will Parchman, a staff writer at Top Drawer Soccer, points out that the majority of American sports fans and pundits think of athleticism in terms of measurables such as speed, strength, size, and power. Every year, the NFL and the NBA (and, less famously, MLS) stage a draft combine in which prospective players are tested in various sprints, jumps, weight-lifting exercises, and position-specific drills. “Most of our games are athlete over skill,” Parchman says. “That’s not to say there aren’t skill elements in games like basketball and football, and to a greater extent baseball. But in terms of our value system, and the way we evaluate athletes here, it tends to be more of a combine mentality.”

Yet even by combine metrics, there are American soccer players who hold their own with the nation’s elite. According to Akron University soccer coach Jared Embick, Yedlin ran a 4.29 40-yard dash in college, which would’ve put him in the top three at the 2015 NFL Combine, among the blue-chip cornerbacks and wide receivers. Stanford and U.S. national team striker Jordan Morris has clocked a 4.5 in the 40, good for top five among 2015 NFL Combine running backs and safeties — and ahead of all prospective quarterbacks, linebackers, tight ends, and (perhaps needless to say) linemen.

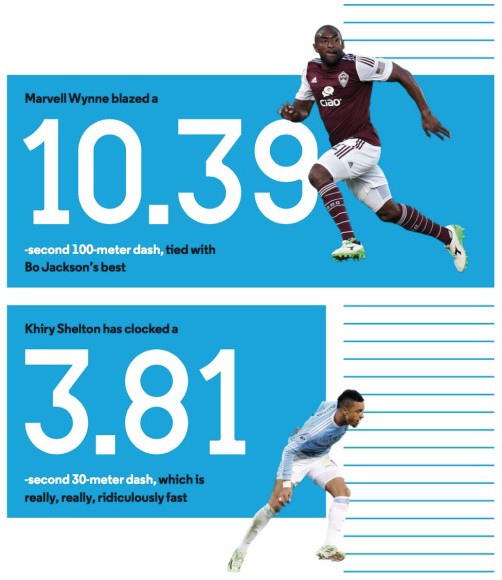

San Jose Earthquakes defender Marvell Wynne, whose father was an outfielder with the Pirates, Padres, and Cubs, ran a 10.39 100-meter dash at Poway High School in San Diego. (Two-sport legend Bo Jackson clocked the same time at Auburn University in 1985.) Portland Timbers defender Chris Klute has reportedly run a 4.3 40, and Montreal Impact striker Cameron Porter — he of the CONCACAF Champions League heroics in March 2015 — produced an NBA-worthy standing vertical leap of 34.5 inches at last year’s MLS Combine.

Go back a generation, and there’s no shortage of high-caliber athletes. Former New England defender and current Revolution coach Jay Heaps played four years of varsity basketball at Duke University, and former U.S. national team goalkeeper Brad Friedel was an all-state basketball player in high school who was invited to try out for the UCLA hoops team in 1990. His successor, Tim Howard, had “several Division I” college scholarship offers for his basketball ability, according to Ed Breheny, his coach at North Brunswick (New Jersey) High School.

Does American soccer have as many raw athletic specimens who can torch a 40-yard dash or punish a blocking sled as the NFL or the NBA do? Hold the outraged tweets and e-mails: No, it doesn’t. But the sport does have its physical marvels, and these are just a few.

All of this takes for granted some standard definition of the word “athleticism,” but what does that really mean?

Take Dennis Kimetto of Kenya, who in September 2014 ran a world-record 2:02:57 at the Berlin Marathon. His average pace per mile that day was 4:41.5. Is that not a staggering athletic achievement? Doesn’t it rank, in its own way, with LeBron James soaring through the lane and posterizing Tim Duncan?

In his conversation with Donovan, Patrick suggested James as an example of an athlete who might’ve altered the course of American soccer had he taken up the game in his youth. I wouldn’t bet against LeBron James in a game of Parcheesi, but if I had to pick a second sport for him to excel in, soccer would not be at the top of my list. James is clearly one of the greatest living athletes, but how would his six-eight, 250-pound frame fit in on the soccer field? It’s not hard to imagine him as a goalkeeper, but outfield positions don’t seem to suit his particular assets, incredible as they are.

We’ll never know how LeBron would fare as a center back trying to pluck the ball off Leo Messi’s left foot (good luck!), but we do know that takes a rather different type of ability than draining a fadeaway three. Back in the day, ABC Sports used to broadcast a show called The Superstars, in which they drafted athletes of every stripe — from Olympic swimmers to NFL and NHL stars to skiers, track-and-field legends, and even soccer players — and set them against one another in a series of competitions far outside their comfort zones. A winner was crowned, decathlon-style, based on who performed the best in the most events.

Tony Lepore, U.S. Soccer’s director of scouting, takes into account a player’s physical attributes, but only in conjunction with his technical ability, his tactical awareness, and his mentality — elements that get greater consideration than a player’s athleticism.

The show was so awesome (where else could you see Olympic pole-vaulter Bob Seagren take on legendary boxer Joe Frazier in a 50-meter freestyle swim?) that other networks revived it several times, including in 2002, when I happened to land on it during one channel-surfing afternoon. There on the screen was the striking image of LaVar Arrington, linebacker for the NFL’s Washington franchise, toeing the start line for the obstacle course opposite Olympic skier Bode Miller.

Arrington stood six-three, weighed 255 pounds, and looked like he’d been drawn by Marvel Comics. Miller looked… lean.

Oh man, I thought, this is going to be a bloodbath. And it was: Miller sprang off the line at the sound of the gun, vaulted the first obstacle — a climbing wall — in one fluid motion, and left Arrington in the dust.

Miller wound up winning the entire competition, defeating three fellow Olympians, a champion boxer, and six NFL stars. This is not to suggest that Miller could have done Arrington’s job on the gridiron, only that different sports require different athletic attributes. Just ask Michael Jordan, arguably the greatest basketball player of all time, who floundered on the baseball diamond.

Even if you employ an “I know it when I see it” working definition of athleticism, the more important notion — and one Patrick’s original question neglects — is how athleticism figures, and doesn’t figure, into the makeup of an excellent soccer player.

“Just because you’re a great athlete doesn’t mean you’re going to transform yourself into a great soccer player,” says San Jose coach Dominic Kinnear, who earned 54 caps for the United States in the early 1990s and has won two MLS Cups as a coach. “If that were the case, then maybe Jamaica would win a World Cup faster than America. Right? If you look at the world championships of track, Jamaica seems to be right up there in every event.”

For Tony Lepore, U.S. Soccer’s director of scouting, athleticism is a small part of the equation. “We always come at talent evaluation with a holistic view,” Lepore says. He and his team take into account a player’s physical attributes, but only in conjunction with his technical ability, his tactical awareness, and his mentality. These elements get greater consideration than a player’s athleticism.

“We’re always trying to make sure that we take a long-term view, ” Lepore continues, “because oftentimes we can make the mistake of thinking that the most talented youth players are the ones that are influential because they’re bigger, faster, stronger, more powerful. But when all things even out at [the] U-20 [level], it’s the other qualities that are more important.”

Parchman echoes this view. “We do have a lot of athletes populating our player pool,” he says. “And they tend to be the guys who flame out first, whereas the guys who haven’t been able to rely on their athleticism — whether they’re smaller or slower or whatever — they have to rely on other things. And those players, in our system, are pushing it forward.” Players in this mold include the slight, skillful Mukwelle Akale, a Minnesota-born attacker currently in Villarreal’s youth setup.

Another critical component driving the American program forward is the academy system. Academy teams, especially the ones run by MLS clubs, have made great strides recently, but it’s important to keep in mind that most MLS academies didn’t open until 2004 or 2005, and the U.S. Soccer Development Academy, which unites the top youth development clubs in the country, was only founded in 2007. Relative to the world’s soccer powers, they have a lot of catching up to do. (By way of comparison, Real Madrid’s academy was founded in the 1950s, and Barcelona’s launched in 1979.) U.S. youth players have only recently been getting exposure to elite training environments, where the speed of play accelerates their speed of thought and enriches their “soccer brains.”

“One of the reasons why some of these worldwide technicians are so good is because they’ve been doing high-level decision making on an earlier and earlier basis,” says Parchman. “We’re talking 12- and 13-year-olds, whereas American players are not necessarily getting that until later on, in the teenage years.”

DeAndre Yedlin is one of those American players, a superior athlete who didn’t receive academy training until he was 18. As talented and successful as he is, Yedlin is now competing against players who have been getting professional-grade training since the age of 12. It’s a head start that no amount of sprinter’s speed can overcome.

American soccer players aren’t lacking in athleticism, but they may suffer from the absence of a monolithic soccer culture such as those that exist in the world’s most successful nations.

Even as the academy system is coalescing, the U.S. has another set of problems higher up the chain because of its unique status in its development as a soccer nation. Kinnear points to the U.S. team that lost 4–1 to Brazil in a September friendly. “Your two center backs are from a Latin American background,” he said, referring to Michael Orozco and Ventura Alvarado. “Then in midfield you have a German, with Jermaine Jones, and so you’re dealing with all of these different backgrounds and making them all play the same way, which can be tough because they’re not brought up that way. If you’re playing against Germany, everyone’s German. Same with Brazil. So they all grew up playing a specific way.”

American kids don’t grow up steeped in the game the way kids from Argentina or the Netherlands or Spain do. And the vast American landscape makes the task of unifying the development system even more difficult.

There’s also the matter of the quality of coaching in the U.S., particularly at the youth level. Lepore says that, after the continued professionalization of the youth academies, “coaching education” is his “biggest improvement target.”

All of these factors rank ahead of improving athleticism on U.S. Soccer’s to-do list. If the American men’s team is going to win a World Cup in our lifetimes, it will be the result of systemic and cultural changes and not because the nation’s future Russell Westbrooks or Bo Jacksons took up the game.

When I contacted U.S. Soccer’s press officer, Michael Kammarman, about this article, he called it an “interesting story line, and one that has many layers.” Here comes arguably the most important layer, and definitely the most abstract one: By focusing on athleticism, Patrick assumes that soccer is primarily physical and that the most physically capable teams will win. But this notion runs up against the intangible yet undeniable fact that the very best soccer in the world is played with the mind more than the body.

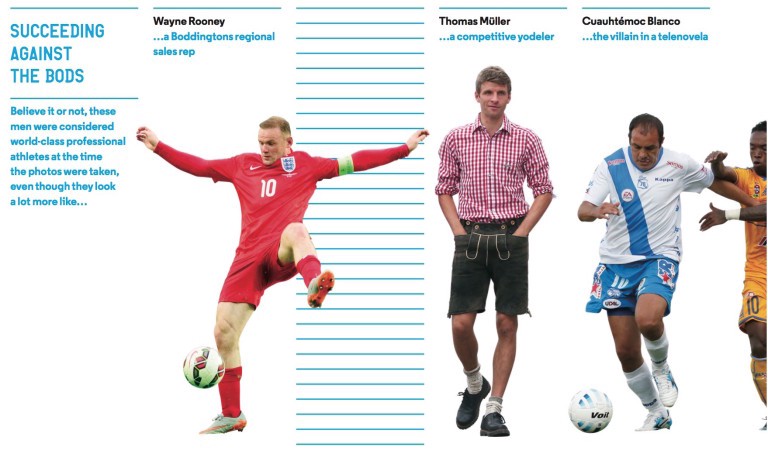

“There are certainly guys like Cristiano Ronaldo who are physical freaks,” says Parchman. But the greatness of a player like Messi, he says, “has very little to do with the fact that he can outrun players. It’s just that he always seems to know where he is in the box, where his teammates are, how to make the killer pass. Thomas Müller of Germany is another great example. There was a picture of him on vacation on the beach, with his shirt off, and he’s just kind of like a stick, you know? But he’s a tactical genius; he just always knows where to be on the field.”

Lepore recalls one of Johan Cruyff’s many famous quotations: “You play football with your head. Using your feet won’t be sufficient.”

This is increasingly true in the modern game, with its high-pressing systems that emphasize tempo and technical efficiency. “The biggest untapped potential lies within the footballer’s brain,” RB Leipzig coach Ralf Rangnick, who played a significant role in the recent renaissance of German soccer, told author Raphael Honigstein. “To get better in the modern game translates into taking in things more quickly, analyzing them more quickly, deciding more quickly, acting more quickly.”

In their ongoing quest to exploit market inefficiencies for competitive advantages, coaches and technical directors will focus even more heavily on the space between a player’s ears, sharpening the intangible qualities Rangnick mentions, to help their players “think” the game better than their rivals.

To paraphrase Proust — who’s almost as quotable as Cruyff — the mainstream U.S. sports journalists’ real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new athletes for soccer but in seeing the game with new eyes.

Yes, soccer rewards a range of athletic qualities, from distance-runner endurance to the quickness, agility, and explosiveness needed for basketball and American football. But, curiously, it doesn’t require these attributes, or certainly not all of them. There is a place in soccer for skillful, cerebral players such as Andrea Pirlo and Müller, and that place is often at the top.

Lepore figures that with two million boys playing youth soccer in the U.S., the athletic element should be covered; the sheer size of the talent pool will ensure a solid percentage of great athletes. But getting the coaching and the infrastructure and the culture in place so that America starts producing Andrés Iniestas and Xavis — these are the elements that the talk-radio types miss when they ask this question.

Wowed by the explosiveness of some NBA and NFL athletes (not to mention the U.S.’s ability to dominate in sports it invented), they view soccer through a prism that prevents them from seeing the game on its own terms. The resulting slanted view perpetuates shopworn hypothetical questions like Dan Patrick’s.

Is there any way to correct it? Well, what would happen if we took the most insightful sports pundits in the country and got them to cover soccer?

John Bolster is an editor for Howler. Follow him on Twitter. Ryan Thacker is the magazine’s creative director. He is @thackerster on Instagram.