Soccer’s hard lessons, for a fan and his country

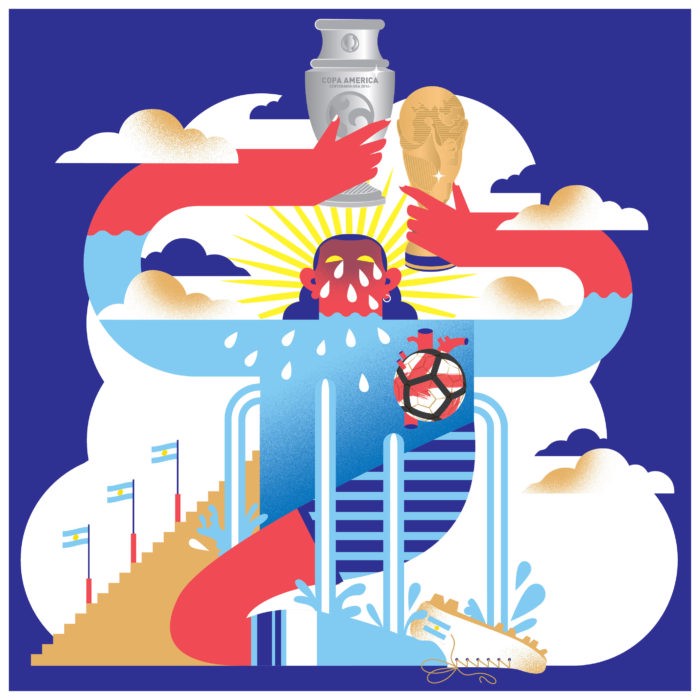

By Juan Sklar | Illustration by Eirian Chapman

Editor’s note: This essay appears in a special edition book we produced for the organizers of Copa América Centenario.

“It feels like being dumped,” I said.

“It’s just a game,” my girlfriend answered.

She’s one of the few Argentines who doesn’t care about soccer. I didn’t have the strength to explain what a World Cup means, how close we were, how beautiful it could’ve been.

“C’mon,” she said. “A month ago it was just a game.”

She had a point. When Brazil 2014 began, I had no expectations. I was connected, I was excited, but the beginning of the cup didn’t feel like the promise of certain glory. It didn’t feel like Italia ’90, the first World Cup I remember. I was in first grade then. We watched the games together in our classroom. No one teaches, or learns, while La Selección is playing.

We remembered 1986, even those of us who had not been old enough to watch the games. Diego Armando Maradona scored an unlawful goal with his hand against the English. Only four years had passed since the Malvinas War. When Diego said the goal had been scored “a little with the head of Maradona and a little with the hand of God,” we smiled and nodded, confident that we deserved divine retribution against the English.

I watched the final, played in Rome, at my grandmother’s house. Nil–nil until the 83rd minute. Edgardo Codesal, the Mexican referee and Argentina’s public enemy ever since, awarded an unlawful penalty to the West Germans. Andreas Brehme scored. Sitting next to my mother, I started crying.

“Don’t cry. Now we’ll go out to celebrate,” she said.

“Celebrate what?”

“That we should’ve won.”

To my surprise, we left the house and found hundreds of people singing songs and waving flags. That scene occurred all over the country — millions of Argentines celebrating that we should’ve won.

Four years later, the World Cup arrived in the U.S. “Now it’s our turn,” I said to my father.

“Why?” he asked.

“Argentina ’78, we won. Spain ’82, we lost. Mexico ’86, we won. Italia ’90, we lost. USA ’94, we have to win. It’s our turn.” I still hadn’t learned.

After two matches, Maradona failed the drug test for ephedrine and was expelled from the tournament. Argentina’s national team never recovered. We were out of the cup after the round of 16. On national television, Maradona swore, on the lives of his daughters, that he didn’t take any drugs. “FIFA has cut off my legs,” he said, and after reminding the audience that he had promised his wife he wouldn’t cry, he began to weep. Millions of Argentines wept with him.

Ever since, the beginning of a World Cup has brought with it the familiar pain and the hopeful feeling that this time it will be our turn — that we, the country of Argentina, deserve the World Cup. The Copa América has not traditionally brought this kind of suffering with it. Perhaps that’s because Argentina has won it quite often over the last hundred years. Or because it was held rather erratically through the ’70s and early ’80s. When Argentina won it back-to-back in 1991 and ’93, the achievement only seemed to solidify our belief that there was little challenge. Occasionally, the coach let his best players skip the tournament altogether, something Brazil did from time to time as well.

Time passed. El Diego retired. France ’98: we went out in the quarterfinals. Korea-Japan 2002: out in the group stage. It was around this time that we started to covet the Copa América. The tournament we used to treat like a condensed version of World Cup qualifying (with odd guests like Japan thrown in) now looked like a respected regional competition. But the series of defeats continued. In both 2004 and 2007, Argentina lost the final match of the Copa América to Brazil and did it in a way that only stirred up our desire to become champions again.

Before every election, politicians talk not of improving the country’s situation but of returning Argentina to where it belongs. This is why, in 2002, after the greatest crisis in the history of the nation — an economic, social, and political meltdown — President Eduardo Duhalde still claimed that “Argentina is a country doomed to success.”

In 2004, we witnessed a particularly dramatic final match. It was tied at one until the 87th minute, when Argentina went ahead with a goal by César “Chelito” Delgado. Brazil equalized in stoppage time and then defeated us in the penalty shoot-out. Argentina was a solid team throughout the tournament. Luck was just not on our side. Three years later, Argentina arrived at the final game after outstanding performances in all of its previous matches. Yet we lost 0–3, again to Brazil. Our defeat included an own goal by Argentina’s captain, Roberto Ayala. Even though we wanted to win, victory escaped us. Our frustration grew.

At the same time, winning the World Cup was becoming an impossible endeavor. At Germany 2006 and South Africa 2010, Argentina was eliminated in the quarterfinals, both times by Germany.

Then, in 2011, Argentina hosted the Copa América. The defeat at South Africa was still in the air, and “Checho” Batista was designated coach of the national team. There was some enthusiasm, since Batista had led La Selección to the gold medal at the Beijing Olympic Games. The national squad included players like Carlos Tevez, Ángel Di María, Sergio Agüero, Gonzalo Higuaín, and Lionel Messi. We expected a triumph. But Uruguay beat us in the quarterfinals, and Batista was immediately replaced. The Copa América can’t bring much glory, but it can certainly get you fired.

By 2014, we had realized that winning the World Cup is not something that anyone deserves and that winning the Copa América is not so simple. Argentina had not won a major tournament in 21 years. Our gold medals at the 2004 and 2008 Olympics were received with some joy, but that is basically an Under-23 tournament. So we went into the 2014 World Cup with no expectations. Nobody thought it was our turn.

However, game after game, our hope started to build. La Selección progressed through the group stage and Round of 16, but that was normal. Only after beating Belgium in the quarterfinals did we start to wonder whether this was, indeed, finally our turn. The semifinals included a beautiful scene: Tied at zero against the Netherlands, we went to penalty kicks. Moments before the shoot-out, Argentina’s de facto captain, Javier Mascherano, approached our goalkeeper, Sergio Romero, looked him in the eye, and said something that the microphones couldn’t pick up but that those of us who were paying close attention read from his lips: “Today you become a hero.” Romero saved two penalties, putting Argentina in the final game after 24 years, and like Sergio Goycochea in Italy, became a hero indeed.

By the time the final kicked off, the sense of expectation had returned. The story seemed perfect: Messi, the greatest player of all time, winning the cup in our neighbor’s house, avenging those defeats to the Germans, healing the wound of 1990.

Of course, we lost, and the pangs of unmet expectations returned. I went home and cried, trying to explain to my girlfriend that what I felt was actual, physical pain. The Argentine sense of collective self is predicated on the idea that Argentina is a great nation and that Argentines should be guiding the world. When we fail, our self-image goes from that of the chosen people to scum of the earth — in soccer, in everything. Before every election, politicians talk not of improving the country’s situation but of returning Argentina to where it belongs. This is why, in 2002, after the greatest crisis in the history of the nation — an economic, social, and political meltdown — President Eduardo Duhalde still claimed that “Argentina is a country doomed to success.”

We are not. There is no fate — only hard work and luck in a world of chaos.

Last year, in Chile, the Copa América stood like a promise of redemption. There was a feeling that we could build on our second-place World Cup finish in 2014. Again we lost in the final. It was said that Lionel Messi was going to be given the award as the tournament’s best player but rejected it. “He is destroyed,” said teammate Ezequiel Lavezzi. Another close defeat in the Copa América, only this time, it really mattered.

And now, the Copa América Centenario is a new opportunity for success. It has taken decades, but the mood in Argentina is now one of wanting success rather than expecting it. A continental tournament, one we have usually appreciated only after suffering defeat in the World Cup, has finally become an actual object of desire for Argentine soccer fans. I’m glad we want to win. I only wish we didn’t need so much defeat to realize who we are.

Juan Sklar was born and raised in Buenos Aires, Argentina. He has published short stories, chronicles and one novel, Los catorce cuadernos.

Eirian Chapman is an illustrator and graphic designer who lives in Melbourne, Australia.