Charming, cunning, graceless, secretive, suspicious, supercilious, loyal, irritable, charismatic, pragmatic, enigmatic, melodramatic, undiplomatic, practically any “-matic”: Has any figure ever polarized soccer fans more than José Mourinho?

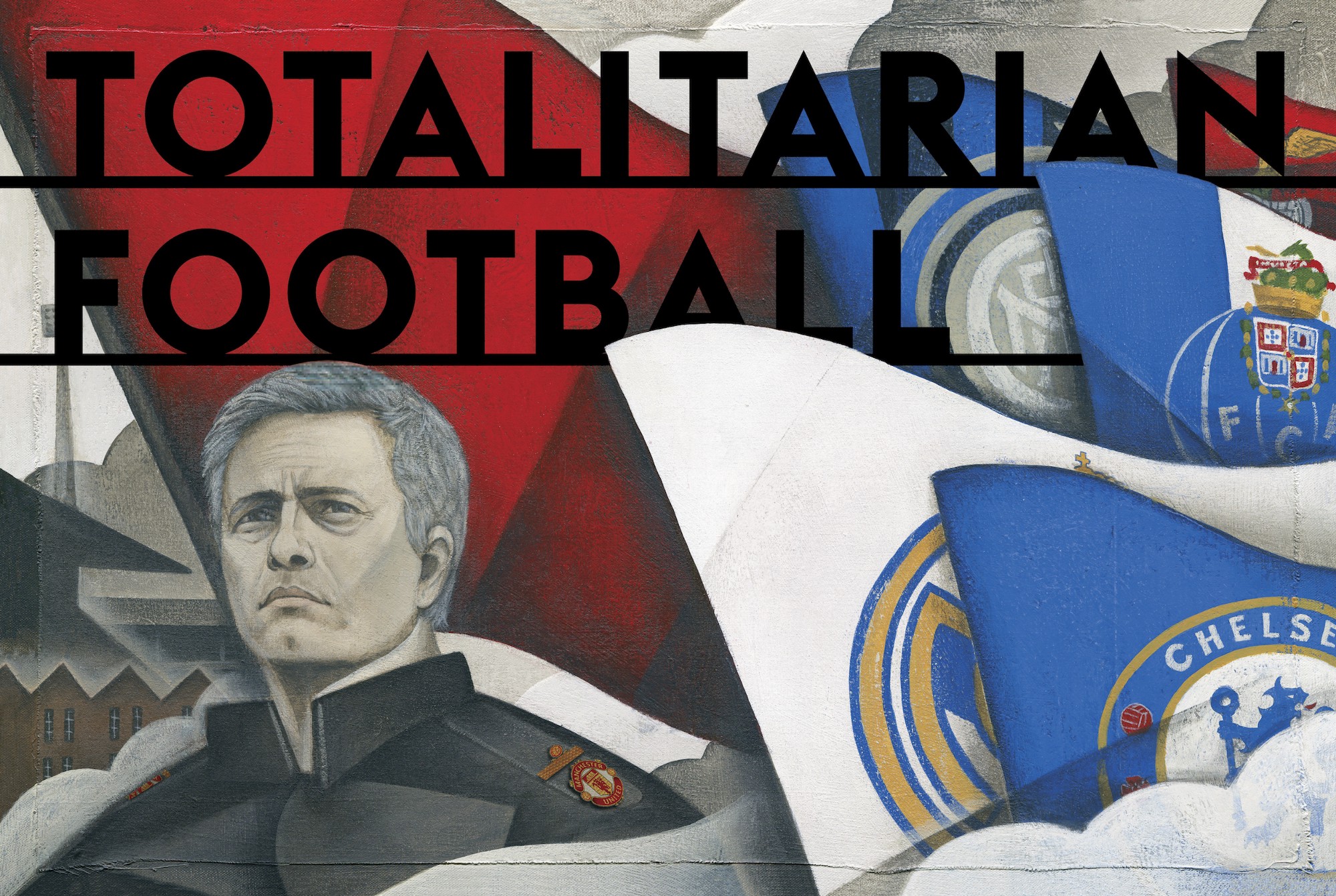

illustration by Paine Proffitt

A protean figure, absorbing whatever traits are projected onto him, Mourinho seems, at times, not so much a person as a flow of pure strategy, always on, pushing buttons, little more than the will to power incarnate. At other times, buttons pushed, the sheer wounded indignation dissolves his precarious self-control into a pool of self-pity.

So, yes, he’s beguiling, witty, fascinating, but he’s also, quite possibly, demented. Properly tapped. And not in the eccentric sense, either, but crazy in the way that Jon Ronson argues in The Psychopath Test that some high-powered leaders are crazy, their madness brimming over to shape history. Hamlet famously confides to Gertrude, “I am not in madness / But mad in craft.” One wonders whether Mourinho’s own “antic disposition” is simply part of his shtick — a tactic, a performance — or whether the fantasy structure animating his all-consuming will to win, his abject gracelessness in defeat, and all of his other excesses make him but another in a long line of paranoiacs and despots of the office, the church, and the playground.

The broad emotional brushstrokes of Mourinho’s backstory are well-known, even if the details remain obscure. The son of a former Portugal goalkeeper, José was a journeyman player who realized his limitations when the president of Rio Ave (where his father was coach) vetoed his selection for a big match. His mother — raised by a sardine cannery tycoon who grew rich under Portugal prime minister António Salazar’s fascist regime and bankrolled their hometown stadium at Vitória de Setúbal — enrolled him in business school, but he dropped out after one day and, determined to have a “big career” in football, undertook a degree in physical education. Unable to emulate his father and determined to prove his mother wrong, José was a highly motivated soul. Later, set on reinventing himself, he removed “professional footballer” from his résumé.

Mourinho’s path to the upper echelons of European football begins as youth team coach at Vitória de Setúbal. He next becomes fitness trainer at Estrela Amadora, transforming muscles into instruments of domination. Then, employed initially as a translator, he follows Bobby Robson from Sporting Lisbon to Porto, and finally Barcelona. Robson and his successor, Louis van Gaal, come to rely on Mourinho’s meticulous tactical dossiers, which leads to an increase in his coaching duties. (Years later, Barça will reject him in favor of Pep Guardiola, a psychic wound that, once Mourinho takes over at Real Madrid, the socios will aggravate by calling him “interpreter.”) Mourinho’s big break arrives in the summer of 2000 following a move to Benfica, where he is swiftly promoted to replace Jupp Heynckes as head coach. However, nine games in he resigns amid political machinations, and after a season at União de Leiria, he moves to Porto, where he follows a 2003 UEFA Cup triumph with victory in the 2004 Champions League. It is an astonishing achievement. Chelsea hires him a month later, and his arrival will doubtless form the opening scene of the Mourinho biopic — to be called The Special One, thus perpetuating the most famous misquote in English football. That initial Chelsea press conference is a masterpiece of self-mythologizing, of surfing the genuinely remarkable Champions League triumph before inflating it to epic proportions.

First, he sets about assembling his charisma machine. With a sharp wit and easy charm, bright eyes, olive skin, and salt-and-pepper hair, he seduces the scribes. The journalists broadcast his arrival throughout the land, reporting that this new manager calls himself “the Special One,” even though he used the indefinite article “a,” not “the.” Students of the Romance languages will tell you that the phrase “a special one” (um especial) is the common Latinate habit of using a noun where English speakers would use an adjective: “I am special,” not “I am the Special One.” Given the proper meaning of “special” as “out of the ordinary,” Mourinho is merely saying, “I belong to the general category ‘special,’” or, in his own words, “I am not one of the bottle.” I am not table wine. But if those in the English media are intent on making a myth of him, it’s not his prerogative to set them straight.

Second, Mourinho creates an origin myth, as do all new despots, effacing the contingency and sheer messiness of their birth. The ascent of the emperor must appear inevitable, necessary, conferred by Providence. Thus, what gets erased from the official history is the fact that Porto’s Champions League success required, in the second leg of the team’s round of 16 tie, a dubiously annulled goal by Manchester United’s Paul Scholes and a last-minute equalizer by Porto’s Costinha. Without this good luck, the tone of the press conference would have been dramatically different (assuming he would even have been offered the job). It would have been harder to convince the public that he wasn’t “of the bottle” — a coach who has gone on to lose six of his seven subsequent Champions League semifinals.

Yet there is a whiff here of messianism, and the scent refuses to fade. He leaves behind Porto, with his description of its “beautiful blue chair, the UEFA Champions League trophy, God, and, after God, me.” Years later he describes his assistant Rui Faria as “the best of my disciples.” But Mourinho doesn’t want to build an empire, a state — quintessentially conservative notions. He is too volatile, too chippy, too antiestablishment. This is something more supple, more unhinged, a cult of personality — “You only need one star at Chelsea: me,” he tells Abramovich upon arrival — that is built for permanent battle. Truly, a Portuguese man-o’-war.

Antiestablishment demagogues tend to conceive of themselves as outsiders. Stalin the Georgian, Hitler the Austrian, Perón the Patagonian: all made much of having come from outside — geographically and professionally — the corrupted space of career politicos. Thus Mourinho, the failed footballer, storms the coaching bastion, purveying a brand of rancorous antifootball that attacks the game’s soul. Or, colloquially, “shit on a stick,” as Jorge Valdano would describe Chelsea’s display in the 2005 Champions League semifinal against Liverpool.

Demagogues are also wont to displace their antiestablishment anger onto an enemy: Jews, Marxists, homosexuals, subversives, referees, the FA, the team doctor. Enemies within, enemies without. Such ubiquitous enemies are the sustenance of a siege mentality, and a Mourinho side is always besieged. After the victorious 2004 final, he left the stadium in Germany without even celebrating with his players, claiming he’d received death threats from ungrateful people within the club. Before his second sacking at Chelsea in December, he said his players had “betrayed” him.

Rycroft’s Critical Dictionary of Psychoanalysis offers the following definition of paranoia: “Functional psychosis characterized by delusions of grandeur and persecution, but without intellectual deterioration. In classic cases of paranoia, the delusions are organized into a coherent, internally consistent delusional system on which the patient is prepared to act.” Mourinho has the paranoiac’s endless vigilance, his constant interpretation of “the signs.” He is a man who has his own press secretary to provide him with daily reports so he can monitor all the slights and barbs and misrepresentations. He pores over the refereeing decisions involving rival teams. Somewhere, his pullulating confirmation bias will whisper, there is always a persecuting agent.

Of course, the siege mentality is a legitimate, if slightly crude, technique to unify the corps. Such psychodynamics unfailingly extend to the style of play when Mourinho’s teams face a big rival, with the defensive block of eight or nine bound as tightly as the fascio (bundles) from which Mussolini derived his political movement’s name.

And here we get to the heart of the matter: the link between paranoia and fascism. “The despot is the paranoiac: there is no longer any reason to forego such a statement provided one sees in paranoia a type of investment of a social formation,” wrote French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in their 1972 book Anti-Oedipus. For them, fascism is to politics as paranoia is to the psyche: shoring up fictive unity under threat from without. The pair coined the term “fascism-paranoia” to describe a coextension of paranoiac attitudes and fascist feelings, at both the local and global level.

Submission of the parts to the whole: this is fascism at its most abstract. The image of the State as glorious, immortal, unified, and orderly must be maintained at all costs, because it is under the auspices of the State alone that the (more or less worthless) individual gains meaning. Woe betide any of the parts that don’t submit to the State’s will. Think of Eva Carneiro, the Chelsea medic who was fired last year after rushing to the aid of a player Mourinho found to be insufficiently injured. In a footballing sense, that means doing your defensive duty. Striker Samuel Eto’o, who played for Mourinho at Inter Milan in 2009–10, tracked back as the wide man in the attacking-midfield trident, as did Mesut Özil (with Mourinho at Real Madrid) and, for a while, Chelsea’s Eden Hazard (until Mourinho’s charismatic authority waned during the 2015–16 season). Dilatory or disobedient characters (at Chelsea, Juan Mata and Oscar) will be hung out to dry, just as subversives were hanged by Italian Blackshirts in the town square. Examples, enemies.

Establishing such order and unity requires a closed system, a rigorously policed inside purged of its contaminants and resistant to the enemies without. Seal the borders! Stop the “voyeurs”! However, the more rigorously you try to control those borders, the more you will inevitably perceive potential threats everywhere, and thus the more you will try to attack. Fascism-paranoia feeds itself, like a fire. The siege mentality starts as a cigarette in a bin and ends up a blazing forest. Little wonder Mourinho hasn’t completed a fourth season anywhere.

Marca penetrated the membrane at Real Madrid by reporting, verbatim, a training ground disagreement in which Mourinho asked Sergio Ramos why he hadn’t marked Gerard Piqué on a corner kick. Ramos replied that Mourinho wouldn’t understand, “because you’ve never been a player” — a cut that simultaneously unraveled the coach’s image of strength and, in its reporting, breached the all-important division between inside and outside.

Total order and complete control is the quintessential fascist-paranoid fantasy, yet it simply isn’t possible in football. In its absence, a fascist state inevitably lurches into a frenetically dissipative attack mode, and in 2004 Mourinho said of his soon-to-be rival Premier League coaches, “If they don’t touch me, I won’t touch anyone. If they touch me, I’ll be ready to hit back even harder.” He is forever launching preemptive attacks, conjuring necessary enemies into existence. His teams contain compliant thugs — Inter Milan’s Marco Materazzi, Real Madrid’s Pepe and Álvaro Arbeloa, Chelsea’s Diego Costa — spreading an atmosphere of fear and terror, haranguing and intimidating referees (the ultimate persecuting agent, in Mourinho’s eyes).

The skullduggery that characterizes Mourinho’s teams emanates from the coach’s suspicion — a positive feedback loop of grievance and chicanery. For José, life is perpetual war in which normal rules are suspended. There is a respect for authority as force, but not as law. Even when the authorities that he so routinely lambastes respond by removing him from the technical area, he circumvents the punishment through text messages (which he used at Porto during the 2003 UEFA Cup semifinal) or by hiding in a laundry basket and gaining access to the dressing room (during a 2005 Champions League quarterfinal between Chelsea and Bayern Munich). Above the law: the very definition of a despot.

Yet what’s always surprising with the downfall of tyrants is how impotent and fragile they suddenly appear: Gaddafi in the concrete sewer; Saddam in the courtroom. Their power is a kind of spell, dependent entirely on the captivation of those entranced. The disinvested body of Mourinho visibly shrunk in his final season at Chelsea. He became an increasingly surly figure, sneering at the injustice of it all, the sheen slowly peeling from his reputation even as he tried in vain to remind the club that it was indebted to his genius. “This is a crucial moment in the history of this club,” said Mourinho as the end approached. “Do you know why? Because if the club sack me, they sack the best manager this club ever had.”

Now, in Manchester, his enemies are once again at the gates, Conte to the south, Pep in the fortress across town. Let the mind games begin.

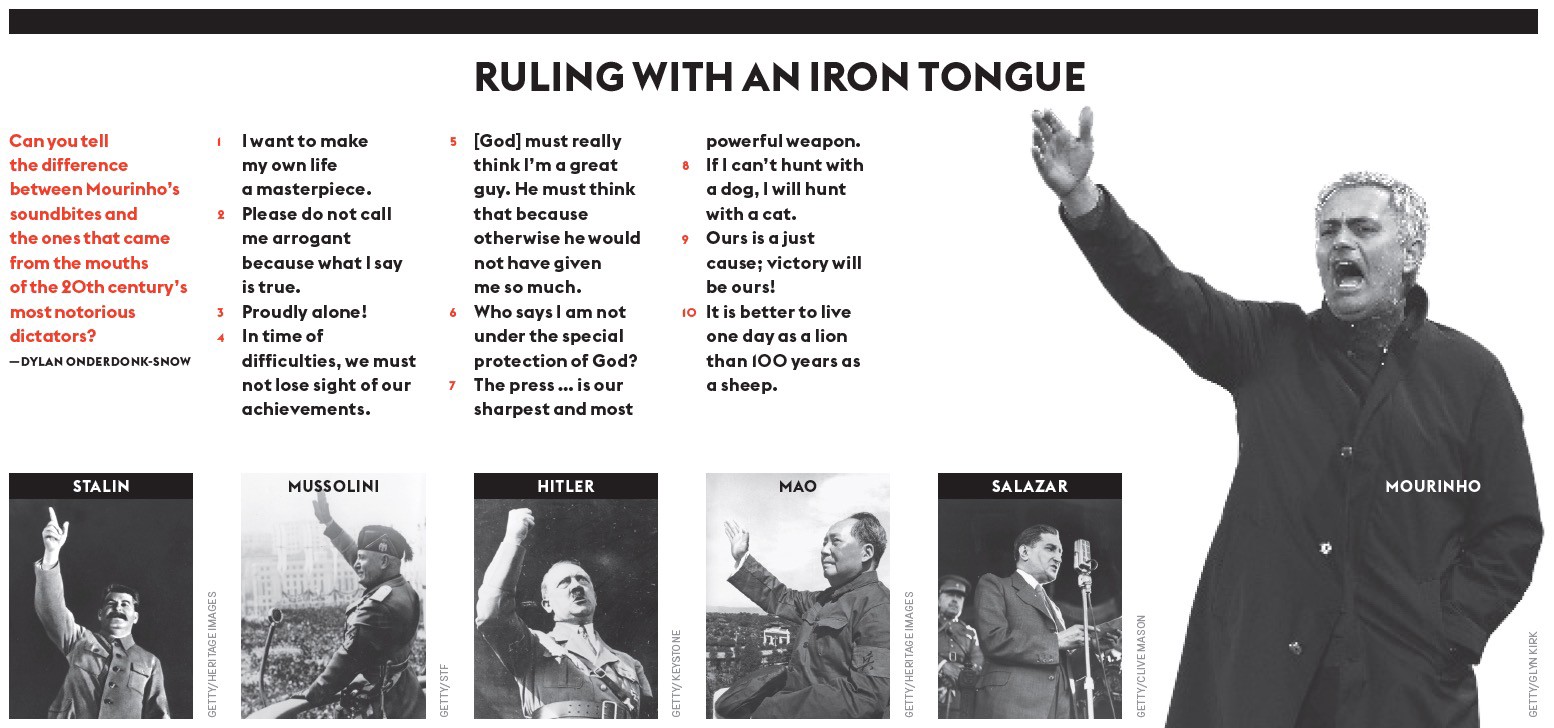

1 Mussolini • 2 Mourinho • 3 Salazar • 4 Mao • 5 Mourinho • 6 Hitler • 7 Stalin • 8 Mourinho • 9 Stalin • 10 Mussolini