What is up with all the bald goalkeepers on the U.S. men’s national team?

Since the summer of 1994, when the United States hosted the World Cup, the U.S. men’s national team has made incredible strides. The evidence for this is everywhere, from the side’s record of 178 wins, 97 losses, and 69 ties to its dominance of CONCACAF and several impressive international showings, including appearances in the 2002 World Cup quarterfinals and the 2009 Confederations Cup final.

The traditional powers of world soccer surely know that it’s only a matter of time before the U.S. overtakes them, but they may not know what has fueled the steady American rise. It wasn’t the spike that came from playing host to the world’s biggest sporting event, nor was it the influence of Major League Soccer, which launched in 1996 and is thriving today with 20 franchises and more expected in the next few years. These things helped, for sure, but they took a backseat — as any astute observer here in the U.S. knows — to the real force behind the U.S. soccer boom: bald goalkeepers.

Yes, glabrous goalkeepers have accounted for 317 of the last 389 U.S. netminder appearances — a span covering more than 20 years, in which the man between the posts was either aggressively balding or completely bald 82 percent of the time.

(A note on methodology. To avoid splitting hairs, we’re categorizing goalkeepers as either bald or not bald. This is somewhat harsh on mid-’90s-era Keller and Friedel, as well as 2006–08 Guzan, but the basic rule is that if you saw him at the time and thought to yourself, “I hope he knows he’s going bald, because the rest of us do,” then that keeper is considered bald.)

The Hairless Era began on July 5, 1994, the day after the U.S. bowed out of the World Cup with a 1–0 loss to Brazil. In goal for that game, as he had been for most of the previous five years, was Tony Meola, a man who wasn’t just not bald, but superfluously so — he wore a ponytail. Perhaps his excessive locks were appropriate as a kind of last hurrah, because Meola ended up being the final representative in a long line of hirsute U.S. keepers.

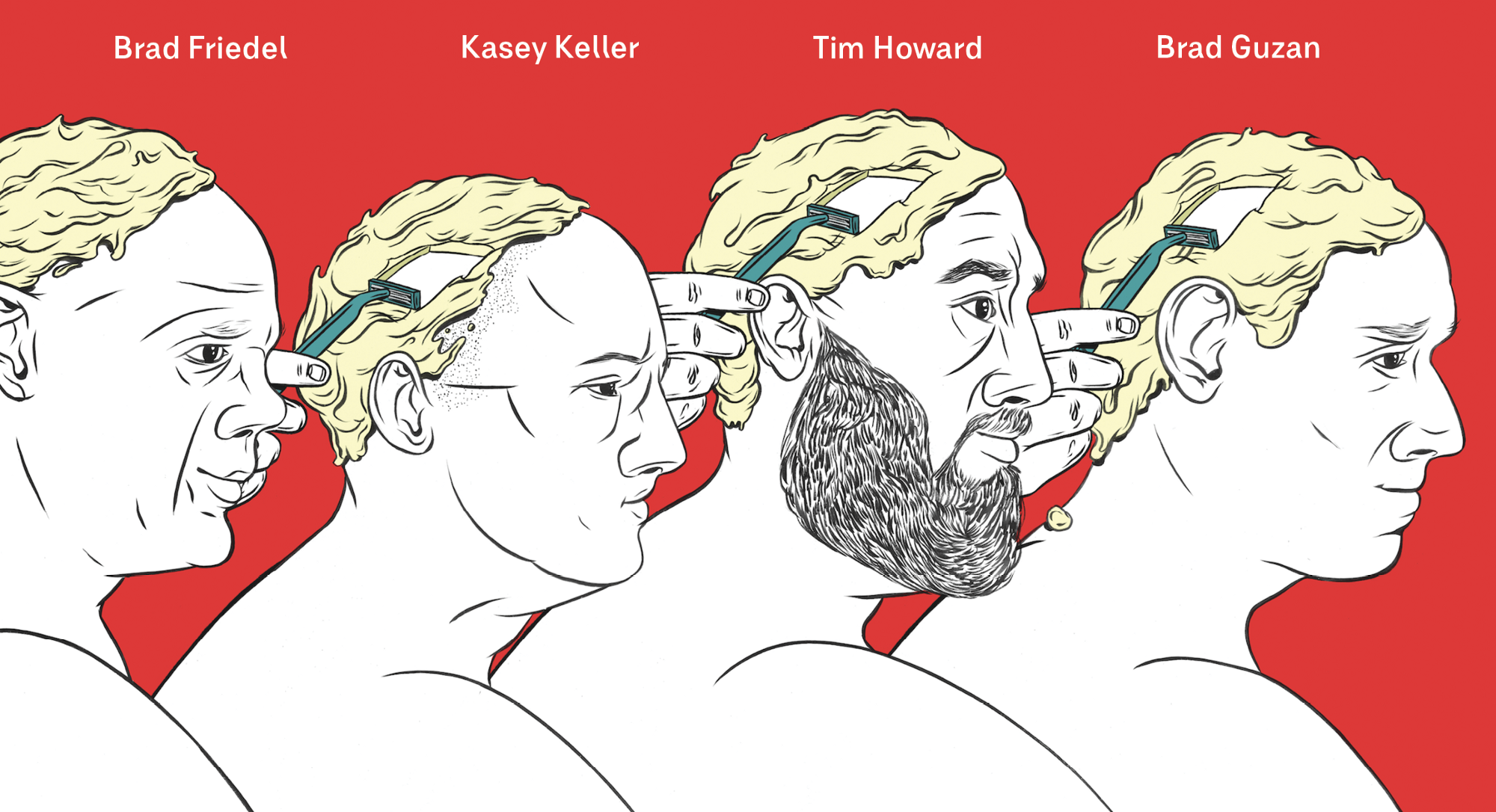

Brad Friedel and Kasey Keller would take the U.S. goalkeeping reins next, under new coach Steve Sampson. Those two appeared in 58 of Sampson’s 62 games, and while neither ever ceded an advantage to the other in the fight for the starting job, both lost very public battles with baldness. Keller went first, losing his hair as quickly as Friedel picked up his faux English accent, but by the time both men made the 1998 World Cup roster, their follicular future was literally crystal clear.

Bruce Arena — himself a former national team goalkeeper, from the Hirsute Era — took over for Sampson following that tournament, and while he usually deployed either Keller or Friedel, Arena seemed to want to find

an heir with hair, giving looks to the likes of Joe Cannon, Kevin Hartman, Tom Presthus, Nick Rimando, Jonny Walker, and Zach Wells. But those goalkeepers would prove to be mere placeholders for Keller and Friedel’s true successor, Tim Howard, who would make his USMNT debut in 2002 and opt for the Mr. Clean look within a year.

Arena’s replacement, Bob Bradley, hadn’t spent money on shampoo since the 1980s, and he enjoyed casting his keepers in his own image. Seven of the 10 goalkeepers Bradley capped from 2007 to 2011 sported a clear dome; in addition to Howard, Keller, and Brad Guzan, Bradley gave games to Marcus Hahnemann, Matt Reis, Luis Robles, and David Yelldell. Even the comparatively hairy goalkeepers he employed — Troy Perkins, Nick Rimando, and Sean Johnson — generally kept it close and clean up top.

Jurgen Klinsmann took the U.S. job in 2011, and has capped more than 75 players since then, many of them new to the U.S. squad. But for all of the changes, the hair — or lack of it — on the starting goalkeeper remained largely the same: Chrome Dome Howard was Klinsmann’s first starter, and Cue Ball Guzan currently gets the nod under the German gaffer.

In the Hairless Era, bald American goalkeepers have completely blocked their more follicularly fulsome counterparts from the most important matches. In World Cup qualifiers, the U.S. hasn’t fielded a goalkeeper with a full head of hair since 2000, when Meola stood between the pipes in a must-win road game against CONCACAF underdogs Barbados.

Speaking of away matches, bald U.S. keepers also hold a huge edge there during the past two decades, playing 89 percent of the Americans’ road games (compared to 77 percent of the matches on U.S. soil).

There are some, however, who would deny the overwhelming statistical evidence. “Hair doesn’t matter,” says nonbald Chicago Fire goalkeeper Sean Johnson, demonstrating why he has played only five times for the U.S. “It’s about how you perform on the field, your physical and mental attributes.”

To be fair, the phenomenon defies easy explanation. Sure, goalkeepers have longer careers than field players, and thus more of an opportunity to develop a receding hairline, but bald keepers aren’t found in these numbers in the rest of the world.

Nor are they found particularly often at any other position on the U.S. national team. Of the 21 most-capped U.S. national team field players, all were active in the Hairless Era, yet only five (DaMarcus Beasley, Michael Bradley, Landon Donovan, Earnie Stewart, Eddie Pope) could be said to be bald or balding — with just as many being famous for having unreasonably excessive amounts of hair (Jeff Agoos, Marcelo Balboa, Frankie Hejduk, Cobi Jones, Alexi Lalas).

Some people have even argued that American goalkeepers aren’t out of line with national averages — that the cluster of bald men at the top of the charts is just coincidence. (Of the 23 keepers who have played for the USMNT in this period, 10 are in the “bald” camp: Tim Howard [104 caps], Kasey Keller [95], Brad Friedel [57], Brad Guzan [30], Marcus Hahnemann [9], Zach Thornton (8), Matt Reis (2), Jon Busch (1), Luis Robles (1), and David Yelldell [1].) Studies show that roughly one-quarter of American men begin to lose their hair by age 30, a rate that is far below that of U.S. national team goalkeepers — and no research to date explains the gusto with which they have embraced the look.

No, the reasons behind this phenomenon continue to evade detection. Some fans have speculated that it has something to do with the Illuminati; others point to an impulse to emulate the great symbol of America, the bald eagle.

The goalkeepers themselves barely have any idea.

“I don’t know and it’s tough to say,” Howard told fans in an online chat. “I like to keep it clean and easy. That works for me.”

“I look worse with hair,” Friedel has said, shrugging off jokes about his look. “I chose to shave my hair off, I chose not to get the implants, I chose not to get the plugs. I like myself bald.”

Thank goodness. One can only imagine the effect on American soccer history had Friedel attempted to keep his hair. Like a reverse Samson, he would have lost his goalkeeping powers as he gained a full head of hair, and the run to the quarterfinals of the 2002 World Cup would never have happened: no penalty saves against Poland and Korea, no Dos a Cero against Mexico.

The magnificently domed Hahnemann, who earned nine caps for the U.S. between 1994 and 2011, thinks a shaved head can be intimidating to opponents. “[It] makes you look mean,” he says, but quickly adds that “the mullet just wasn’t a good look for me.”

Keller has also referenced his “mullet stuff in the ’90s” before he cleaned it up, perhaps due to the aerodynamic benefits. Guzan lent some credence to this idea, once telling a fan that there was “something about the hair that slows us down while diving.”

Extreme stress has been known to cause hair loss, and goalkeepers, with the mental aspect of the game at the forefront of their job, could be at risk.

“I don’t know if that has anything to do with it,” says Matt Reis, who earned two caps for the U.S. in the midst of a long, successful, and hairless MLS career. He saw the decision to shave the “hair island” on the front of his head and go fully bald as “more practical. I haven’t had a bad hair day in 12 years or so.”

We understand the impulse to accelerate the process — to go from patchy “balding” to streamlined “completely bald” as quickly as possible — but the roots of the issue still need to be addressed. What causes this intersection between balding and backstopping? What gives the clean-shaven their penchant for clean sheets?

“I think you’re already predisposed,” says Reis. “If you’re of a like mind — and share a like recessive gene — then you’re going to become a goalkeeper.”

We would add that if you’re a young goalkeeper trying to emulate your heroes like Friedel and Keller, why not try to do everything they did?

One goalkeeper had that instinct, and the pressure was immense.

“It made things kind of tough on me growing up,” says Clint Irwin, the follicly endowed goalkeeper for the Colorado Rapids. “If I wanted to accomplish my goals, it seemed like achieving baldness was paramount. At the age of 16, that’s a tough pill to swallow.”

Even so, Irwin doesn’t necessarily think that coaches denied him opportunities based on his (hairy) condition.

“I didn’t notice any discrimination up front,” he insists. “It wasn’t like, ‘We don’t think you’re very good right now. Come back when you’ve lost your hair.’ But discrimination is oftentimes latent.”

Reis noticed an immediate difference. “I shaved my head, and doors started opening up for me,” he says. Though he says he can’t confirm that’s the reason he became the starter for the New England Revolution, he also “can’t deny it.”

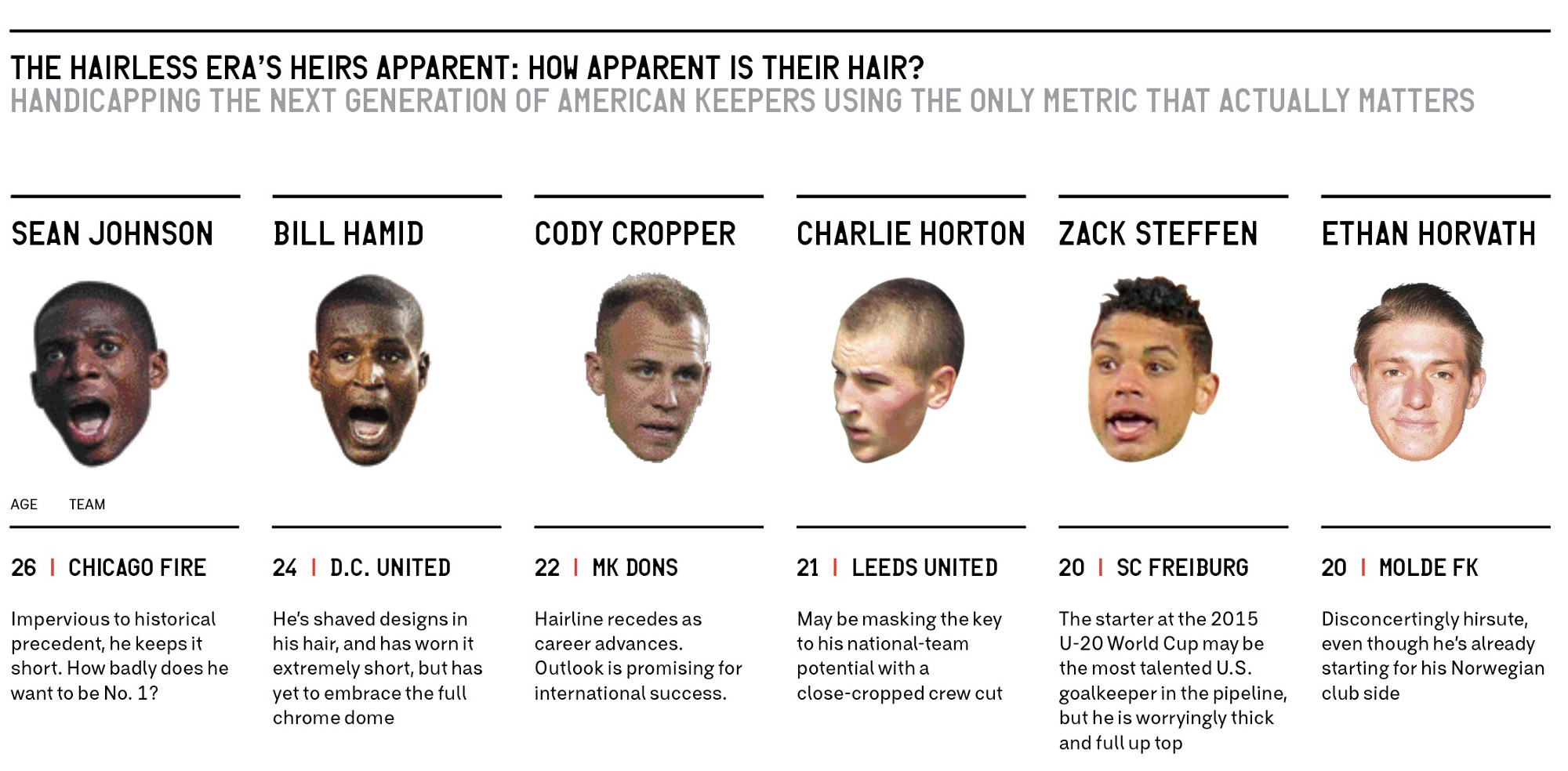

But now, four years into the Klinsmann regime, there are worrying signs that the Hairless Era may be drawing to a close. The current U.S. national team boss has used nonbald goalkeepers a stunning 27 percent of the time, way ahead of his predecessors Arena (19 percent), Sampson (14 percent), and Bradley (11 percent).

Most of this comes from an increased reliance on Nick Rimando, who has earned 16 of his 21 caps under Klinsmann. The Real Salt Lake keeper has been respectful enough to keep his hair closely trimmed, but it’s clear he could desecrate the tradition at any time simply by putting the scissors away for a few months.

While the comfortingly hairless Guzan looks to have a firm grip on the starting job for now, Klinsmann appears not to recognize the pattern of baldness that has led to America’s emergence on the international stage. He even tempted fate recklessly in March 2015, when his roster for a pair of European friendlies didn’t include a single bald keeper (Rimando, Cody Cropper, and William Yarbrough).

Should Klinsmann — or any future national team coach — choose to ignore the overwhelming evidence in support of fielding a bald-pated keeper, the consequences could be disastrous. After all, the Hairless Era has given the USMNT a demonstrable advantage over the rest of CONCACAF. It has also boosted the Americans’ international profile and lifted the sport to new heights in this country.

Unceremoniously dropping the curtain on that era could spell the end of a three-decade-long surge of U.S. soccer success and send it spiraling down the drain, like so many loose strands of you-know-what in the shower.