Beginning in the late ’90s, Swansea City’s mascot was accused of all manner of fowl play, from inciting riots and head butting a referee to attacking other mascots and even a rival coach, all while saving the club’s financial fortunes. Then the nine-foot-tall bird became the prime suspect in a serious assault.

by Jeff Maysh | illustrations by Elena Gumeniuk

The future looked bleak for Eddie Donne. In March 1998, he was 21 years old and living in Swansea, a gray, industrial seaside city known ironically as the Welsh Riviera. Donne was the overworked groundskeeper at the Vetch Field, an obscure stadium named after an obscure vegetable that used to grow there. The Vetch was home to an obscure soccer team, Swansea City, that was drowning at the bottom of the United Kingdom’s lowest professional division. Relegation into the GM Vauxhall Conference would officially reclassify the team as semiprofessional, which it could not survive. Yet Donne spent his days pushing a hand mower over the Vetch Field’s lumpy grass, mixing white paint in an old soda bottle, and marking the sidelines with a paintbrush. His wage was paid in coins from the turnstiles. Attendance had dropped below 4,000. But Donne was a lifelong fan of the Swans, and he liked to say that he worked “for the love of the badge” — which, considering the circumstances, had to be true.

Industrial decline brought on by the closures of coal mines and factories in the 1980s made Swansea, with a population of just over 225,000, feel more like the Welsh Detroit. Unemployment was rising and there were few opportunities. So Donne was deeply concerned when the football club sold to a windshield replacement company, Silver Shield, for a nice round £100 ($147). That price would have been a bargain if not for City’s $2 million in debts. The new owner, the press concluded, was “either brave, daft, or both.”

Silver Shield boss Neil McClure, who was described in When Saturday Comes as a “large, camp waddler with a horrendous comb-over,” called an emergency financial meeting. At a country club in Oxfordshire — McClure avoided Wales whenever possible — he met with his new commercial director, Mike Lewis. The bespectacled Welshman was a marketing executive with a flair for publicity stunts. At Tottenham Hotspur, he had revolutionized the halftime show, bringing to one game in 1983 several fire-eaters, the world’s tallest man, an escapologist, and judo champion Brian Jacks. At the meeting, McClure demanded to hear Lewis’s plan to save Swansea City.

“I was dancing on my feet,” Lewis admitted in his memoir. “I suggested … we should have a club mascot.” He proposed a giant swan, naming it Cyril. Mascots were a luxury of rich teams, and the idea irritated McClure. “Neil’s hate relationship with our newborn bird started that day,” Lewis wrote.

Back in Swansea, sewing machines rattled to life and feathers went flying through the air. The swan cost a staggering $3,678 and looked like the mother of all Halloween costumes. Cyril was nine feet tall and all white, like Swansea’s famous uniform. He had a long neck, wild eyes, and wide, flappy wings. On August 8, a local soldier debuted Cyril in the season’s first home match, against Exeter City, sliding down a rope from a rusting, 90-foot-tall floodlight.

The proud Swansea fans, blue-collar folks who call themselves “Jacks,” had been hoping for a big summer signing. Instead they got a big swan. The stunt was a dud. In his office at the Vetch, Lewis realized he needed someone to breathe life into Cyril. Someone like Eddie Donne.

The groundskeeper would do anything for the Swans, he said — anything but that. When I meet Donne in Swansea in May 2015, he is 38 and stout, with a round, mischievous face. He describes in his singsong Welsh accent the impossible workload at the stadium, how he cycled to the Vetch through midnight thunderstorms to cover the field, disrupting dates with his new girlfriend, Rebecca, also a Swans fan. But Lewis convinced him: Cyril was Swansea’s savior. He gave Donne two rules: don’t speak and never remove Cyril’s head in public. On August 11, Donne tipped back a prematch pint of ale at the Clarence Inn, next to the Vetch, where Swansea City was scheduled to play its home League Cup leg against Norwich City.

“Boys, I can’t believe I’ve got to do this,” he told his mates, holding aloft Cyril’s silly head. Just before kickoff, Donne slipped into the costume. That’s how it began, he says: “I just went for it.”

Norwich City looked more than two divisions classier than the Swans, whose defending was slapstick. Emboldened by beer and outraged by a bad call from the linesman, Cyril sprinted along the sideline, flapping his wings in protest. Inside the costume, Donne could barely see. At the dugout he collided with Norwich City’s assistant manager, Bryan Hamilton, knocking him to the ground.

“Hamilton got up and faced Cyril and made some threatening gestures,” Lewis recalled. He couldn’t believe it. Neither could the crowd. Was a giant swan about to brawl with the rival coach? Then Norwich scored. The visiting fans climbed the fences, angry fists punching at the air, hounding Cyril.

“I started pecking them off,” says Donne, laughing. Then, unbelievably, Swansea scored to tie the game, and “it just went mad.” Cyril dove into the North Bank, the rowdiest stand at the Vetch, and crowd surfed as the home fans chanted, “Hoo-li-gan! Hoo-li-gan!” — the highest of compliments. Donne had toiled away in the stadium without thanks since he was 17. Now he was riding a wave of hands, a superstar. After the game finished 1–1, Donne made sure nobody was looking, removed Cyril’s head, and picked up his pitchfork to repair the field.

Cyril had become an instant hero, but Norwich City felt differently. The team complained to the Football League and barred the mascot from the return leg. Without Cyril’s support, Swansea lost and exited the cup. But the city was buzzing. “Whoever was inside the costume,” a hard-core Swansea fan named Leon, 30, tells me, “he was a real Jack.”

“Feathers Ruffled by Swans Mascot!” read a headline in the South Wales Evening Post. At the next home match, Cyril received a standing ovation. Donne lived up to Cyril’s new reputation as a pantomime villain: At halftime, when local kids were invited to shoot at goal, clumsy Cyril would save their shots and foul them. When the fans booed, he turned tail feather and mooned them. But he was one of them, a real Jack. Swansea fans standing at the Vetch’s grim urinals might look up to see a giant swan unzipping at their side. (Eddie: “I cut a hole in my costume so I could go for a wee.”)

“There was nothing better than coming out on the pitch,” Donne says. “Honest to God, the players had me in their team circle.” The Vetch became his stage, the costume like a second skin — “like Batman and Bruce Wayne,” he says. And like the caped crusader, Cyril’s true identity was “a closely guarded secret,” according to the BBC.

Lewis cashed in on Cyril with a children’s book and a pop song that sold out in Swansea called “Nice One Cyril.” The large waterfowl was voted Personality of the Year by readers of the South Wales Evening Post. Telephones at the Vetch were chirping. People wanted Cyril to attend their parties, events, dinners. Donne juggled his groundskeeper duties with Cyril’s social calendar. He opened a new store, danced on tables, and sent merchandise flying. He was mobbed as fans tried to touch him.

“I loved it, right? It was a dream,” Donne says. “I’d get up in the mornings.… ‘Where’s Cyril going today?’”

The last place he would imagine was jail.

Eddie Donne is driving us through Swansea, which is actually lovely. We pass a sign for a village called Brynhyfryd, one of those Welsh spellings that looks like Cyril mashed it out on a human-size keyboard. Donne recalls driving to events in his tiny Nissan Micra, one wing out the window, Cyril’s head protruding from the sunroof.

“I needed a driver,” he says as we arrive at a steel gate shaped like a swan. Behind it, a wheelchair ramp leads to a tiny bungalow heaving with game-worn Swansea jerseys, autographs, and ephemera. This is the home of season ticket holder Kevin Davies, who, at the height of Cyril’s fame, invited the bird to visit his Swans-mad son Josh, then 11 years old. Josh has cerebral palsy. The trio became fast friends, hitting the road in Kevin’s minibus and delivering Cyril to weddings, hospital visits, and, on one occasion, a solemn sprinkling of ashes at the Vetch.

Josh whirs his wheelchair into the kitchen.

“Remember when you taught me the swearwords alphabet?” he says, chuckling.

Donne shoots me a look.

“They say, ‘You can’t talk to Josh like that,’” he explains.

Josh is roaring with laughter. He’s now 24.

“The only swearword we didn’t use was the C-word!” Josh says.

We flick through photographs of their adventures in Josh’s treasured album. I see Cyril and Josh laughing at a kids’ party, Cyril interrupting a couple’s anniversary, Cyril in a hospital bed pretending to be sick.

“One Christmas, we were at the hospital,” Donne says quietly. “There was this one kid in there who never smiled — never smiled once since she’d been in there. She sees Cyril and she just came to life.”

Kevin pours Josh a cup of tea in a plastic beaker and says, “All the nurses started crying.”

Josh tells me that Cyril’s antics revitalized the halftime show at the Vetch. Inspired by Cyril’s press, a plague of mascots converged on Swansea, seeking fame. The bowling alley had one, as did the snack brand Monster Munch. A kangaroo from an Australian pub hopped up. And a local Mongolian restaurant created an inflatable Mongol warrior.

“He was massive,” Donne says, “like Goliath. So I ran into him; I had boots on. I deflated him, didn’t I!”

We all laugh as Donne recalls how Cyril stood on the warrior’s chest, the air whistling out. Cyril transformed the Vetch into a Roman arena, and the crowd loved it.

It was a most violent era for mascots. In 1998, a Bristol City match against Wolves was marred by an on-field punch-up between a furry wolf and a pig. Aston Villa’s Hercules the Lion was fired after “hugging and kissing” Miss Aston Villa, Debbie Robins, at a game against Crystal Palace. The first annual Mascot Grand National race descended into carnage at the first furlong; a man in costume is a dangerous agent.

“Being anonymous can liberate people to be uncivil,” says Dr. Robin S. Rosenberg, a clinical psychologist in California who studies the effects of wearing costumes. “There is even more disinhibition as a result of being nonidentifiable.”

This is especially true when your character is a nine-foot fighting bird.

Friday the thirteenth in November 1998 was a Welsh night from a Dylan Thomas poem: starless and Bible black. More than 10,000 fans poured into the Vetch to watch Swansea play Millwall in the first round of the FA Cup. Millwall, from South London, is infamous for fan violence. Before the match, Cyril taunted the opposition fans as usual. Then, before kickoff, he approached referee Steve Dunn on the field.

“All he said to me was, ‘Have I got to put up with this all game?’” Donne recalls. “And I nodded my head, and I butted him” — accidentally, he insists.

Against all odds, the Swans went 2–0 up, and when they scored a third, Cyril sprinted onto the field — a capital sin. He dove into the players’ celebrations; the fans went berserk. Then, Mike Lewis recalled, “with a swing of his right boot he sent the ball rocketing into the bread box [head] of a Millwall player, dispatching him to the ground.” The referee tried to restore order and restart the match, but Cyril was just finding his stride. Overcome with emotion, he ran to the linesman and used a massive wing to caress the man’s bald head. The tie had descended into a farce, the funniest game many fans could remember, and it was all thanks to Cyril.

The Football Association of Wales accused Cyril of bringing the game into disrepute. But the Swans were on a cup run! On January 13, 1999, they beat West Ham in a third-round giant killing, a night of such high passion that exactly nine months later, Donne and two Swansea players would become fathers.

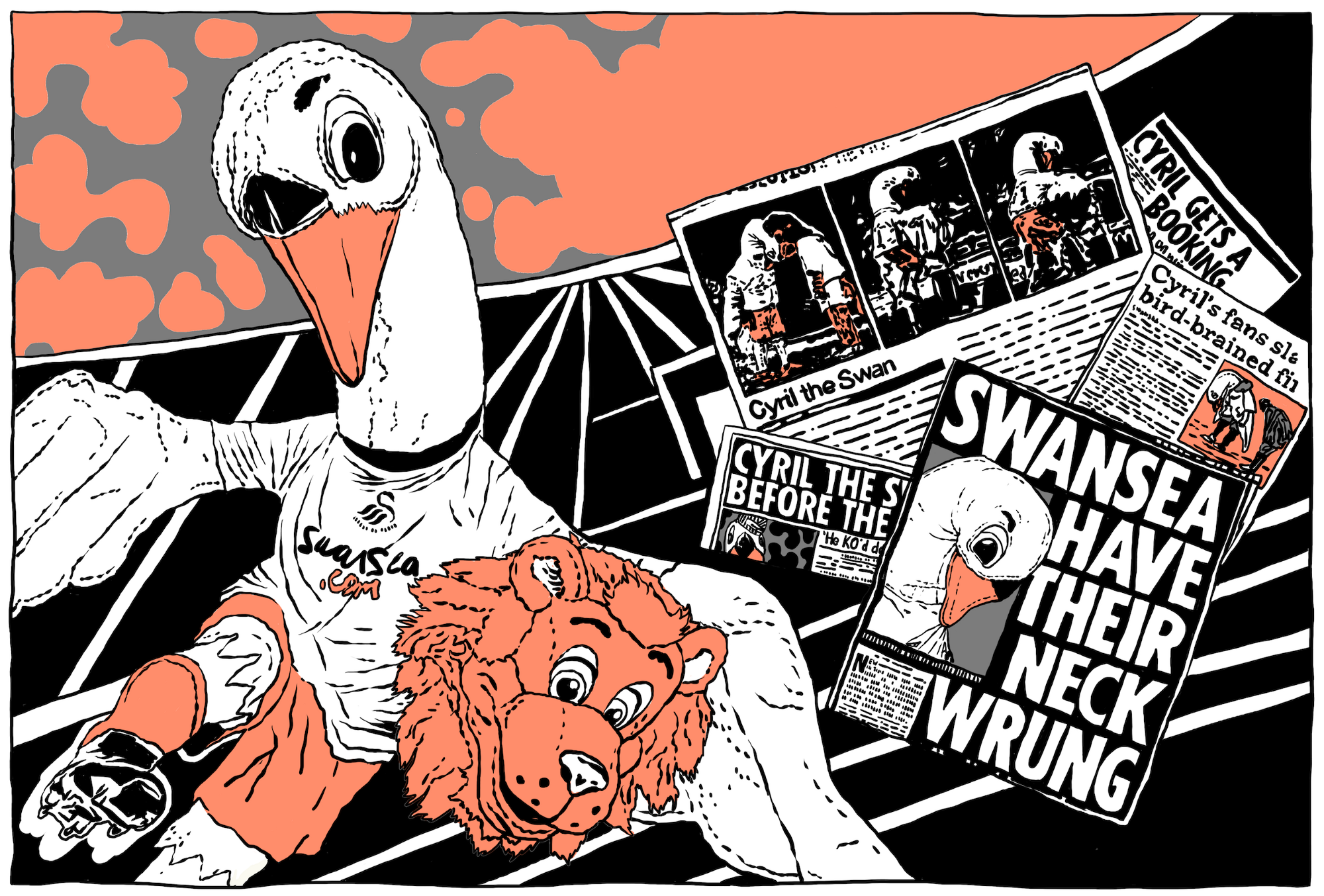

It took a Premier League side, Derby County, to knock Swansea out of the cup. This happened in January as the Welsh FA scheduled a hearing for Swansea City and its mascot. The press went Cyril-crazy as newspapers typed up Cyril EGGS-clusives about his BIRD-BRAINED antics. They lauded him for landing in HOT WATER, getting his WINGS CLIPPED and his NECK WRUNG. On April 23, 1999, Cyril’s hearing was held at Cardiff’s Posthouse Hotel to avoid a media circus at the courthouse. Jokes aside, receiving a heavy fine or being forced to play matches without spectators could ruin a club like Swansea. And if Cyril sunk the Swans, Eddie Donne would surely be unmasked and run out of town.

Neil McClure hired Britain’s most famous sports attorney, Maurice Watkins, to defend Cyril. In 1995, Watkins had represented Manchester United star Eric Cantona after he kung fu kicked a spectator. He wanted Cyril kept away from the hearing because, Watkins told me via e-mail, he was “unpredictable to say the least.” This, he said, almost caused Lewis to “have apoplexy as the interest in the case had already generated huge sales of Cyril memorabilia, and [Lewis] had just commissioned the purchase of thousands of Cyril statuettes.” Donne avoided the TV crews and fans out front by sneaking in a back door and carrying Cyril in a bag. When Donne poked Cyril’s head out of a window, the mob went wild and began chanting, “Save our swan!”

Welsh FA chairman Alun Evans and two officials were sitting behind a long table in a barren conference room when they called for the defendant.

“They wanted to see what my vision was like,” Donne says. Cyril kicked the doors open and staggered inside. “I was falling over on purpose,” he says. “There was a plate of biscuits, so I pecked them, knocked the plate over.” As the biscuits went flying, the FA officials looked on in disbelief.

When Lewis explained that Cyril was a mute swan, the chairman instructed him to act as a translator.

“Ask Cyril, Mike, can he see a football at his feet when he is wearing his costume?” said Evans.

The swan shook his head: no.

“Ask Cyril, Mike, did he intentionally kick the ball in the direction of a Millwall player?”

Again, the answer was no.

“Mr. Watkins,” the chairman barked, turning to the lawyer, “were you aware that Cyril patted an official on the head shortly after Swansea had scored their third goal … after encroachment on the field of play?”

“Yes, Mr. Chairman,” Watkins said. “Cyril thought that he had seen a coin thrown at the linesman and went over to console him.”

Brilliant, Maurice, brilliant, Lewis recalls thinking.

Cyril was dismissed from the room. As he was leaving, Donne saw referee Steve Dunn sitting in a chair in the corridor.

“I dipped my beak in his coffee,” he says.

Five hours later, the committee had reached a decision, slapping Cyril with a $1,470 fine and banning him from the sidelines for a whole season. When Cyril appeared outside in a blaze of flashbulbs, McClure addressed the media. Inside the costume, Donne was panicking about the fine. Rebecca was pregnant with their first child, and besides, “Money wasn’t great with the Swans,” he says. The club ended up paying the fine; Cyril, after all, was a moneymaker. In Cyril’s absence, the Swans won Division Three and earned promotion to Division Two.

Meanwhile, during his suspension, the swan became a full-time celebrity. He even landed a role in Aladdin at Swansea’s Grand Theatre. On May 28, 1999, the Queen visited Swansea and was photographed near Cyril. “Who’s that with Cyril?” people joked. On a late-night karaoke TV show, he roughed up former England manager Terry Venables, and afterward, at a party in Cyril’s London hotel room, Donne says cigarette smoke set off a fire alarm, causing the evacuation of guests, including Romania’s rugby team. Then, during the Bumbles of Mumbles variety show, Cyril attempted to stage dive but ended up crashing into the band pit.

“I let myself down,” Donne says. “The security guards were chasing me. I had to run out the emergency exit.”

As soon as his ban was over, Cyril returned to action. Donne was glad to be back. The fans were delighted. Everyone was captivated by Cyril, apart from McClure.

“He would privately threaten me,” Lewis recalled, “with statements such as ‘It will be you or that fucking bird, Lewis.’”

The Welsh FA called the NFL for help in creating a mascot code of conduct and forced Swansea to erect cages at the Vetch to prevent fan invasions.

“As groundsman, I put them up,” Donne laughs. “I was protecting myself from myself.”

Lewis warned Donne over and over about Cyril’s behavior, but the swan persisted, disrupting a National Lottery draw that was televised live from the Vetch. Donne says viewers were told that if the bonus ball was an odd number, Cyril would be replaced, and lottery officials went so far as to unveil a black swan called Syd.

“They had to scrap that idea,” Kevin, Cyril’s driver, tells me. “The fans started chanting, ‘You black bastard!’”

More Cyril wannabes followed. The breakfast cereal Weetabix launched a TV ad featuring a naughty soccer mascot, Goldie the Goose. Swansea City threatened legal action.

Then on February 11, 2001, real trouble brewed when Swansea met Millwall again, this time in a League Two clash. After Cyril’s previous run-in with Millwall during the FA Cup tie, fans of the visiting club considered him a public enemy, and Lewis ordered Donne to avoid them. Outside the Vetch, 300 police officers mounted the biggest antihooligan operation in Swansea’s history, seizing weapons that included a steel axe and an item described in the newspaper as “a Chinese martial arts rice flail.” A stadium officer warned Cyril, “Keep a low profile and nothing goes wrong.”

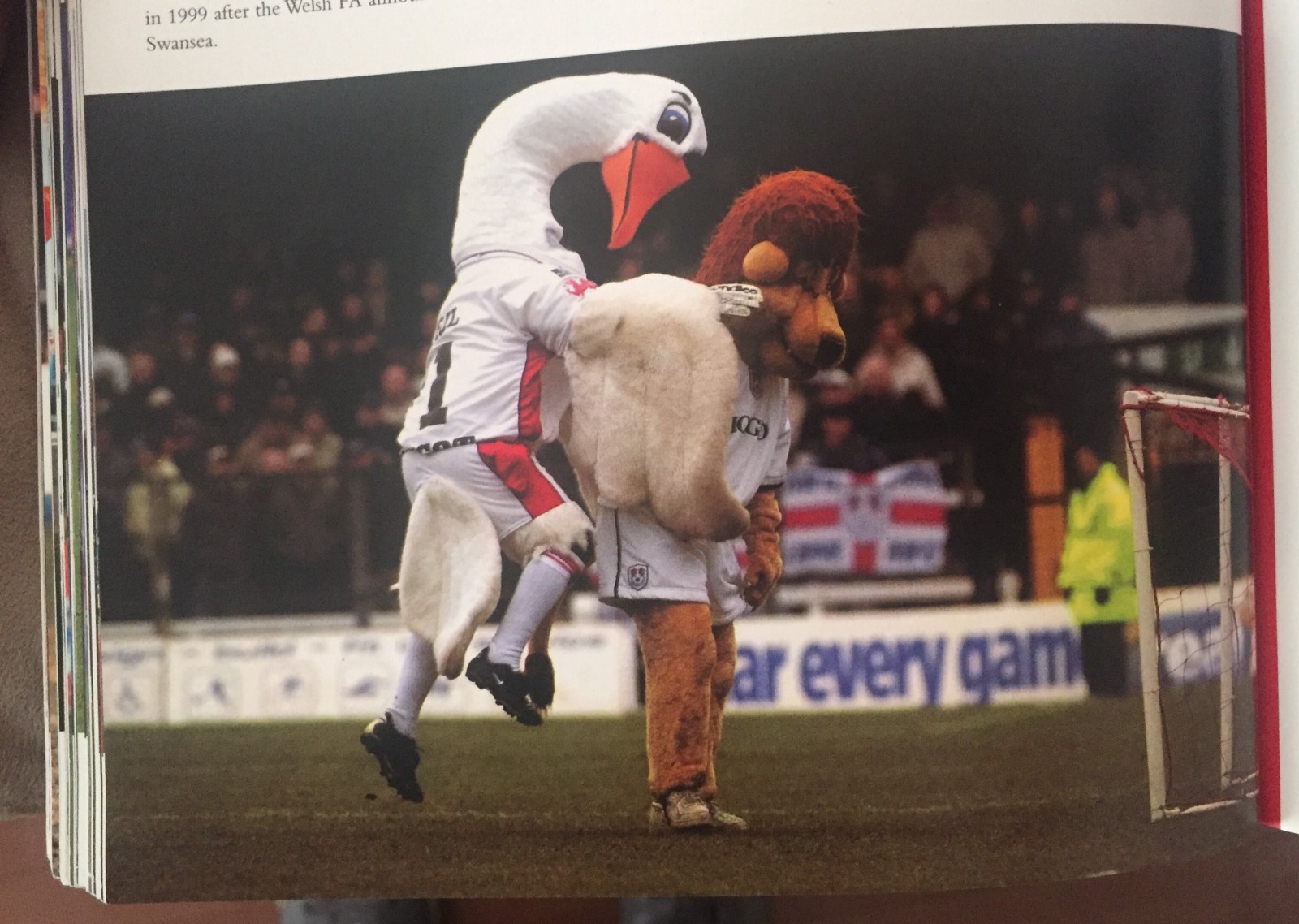

But keeping a low profile is exceedingly difficult for a nine-foot swan. At halftime, when Donne was to take spot kicks against the Millwall mascot, Zampa the Lion was nowhere to be seen. Then the sea of South Londoners parted, and out he marched, straight from the stands. This was unusual. Donne typically met the rival mascot before each match.

“We have a chat, have a beer and a half — that’s what mascots do,” he says. “They’d put someone in the costume to fill me in” — to beat him up. Then Donne heard a Millwall hooligan shout, “Rip his head off, Zampa!”

As Cyril stomped onto the field from his position in front of the Swansea fans, a hush fell over the Vetch. Swan and lion were now standing beak to snout in the center circle. Zampa was six feet tall and heavyset, his face permanently frozen in a shit-eating grin.

“What’s going on then?” Donne shouted at his colleague, but the man inside Zampa gave no reply. Instead he threw a jab at Cyril. Here we go then, thought Donne. “I’m looking up at the stadium control room, and I’m saying to myself, ‘Eddie, behave!’ I’m the groundsman. It’s my life.”

But Zampa kept swinging. Then he reached to pull off Cyril’s head, a serious no-no. Donne’s response was swift.

“I gave him an uppercut,” he says.

The crowd roared, thousands of people cheering on this rumble in a cartoonish jungle.

“His head came off in my hands,” Donne recalls, so Cyril clomped off the field and drop-kicked it into the Millwall stand. The headless lion limped away.

“Don’t fuck with the Swans!” Donne shouted after him.

Police officers dashed onto the field. “I just ran straight down the pitch, down the tunnel,” Donne says. Two officers were right behind him. Cyril skidded around a corner and slipped into a dressing room. The policemen hammered on the door, shouting, “Where’s that bird? Where’s that mascot? We need him out here!” Donne shimmied out of the costume and calmly walked out another door. The police found Cyril in a pile on the floor. Donne says that when his girlfriend, Rebecca, a new mother, saw photos of the brawl, she told him, “There’s absolutely something wrong with you!”

Swansea finished the 2000–01 season second to last, and the club was relegated back to the Third Division. Despite its misfortune on the field, Lewis claimed the club’s income had risen from £65,000 to £600,000 in three years — the equivalent of $1 million in today’s money — thanks in part to Cyril. The Sun came in as a sponsor, purchasing the Cyril-mobile, a Mitsubishi flatbed truck. However, the club was hemorrhaging money as fast as it was earning it and falling deeply into debt.

Lewis found his feathered creation to be uncontrollable, telling a journalist, “Cyril is often seen in the town’s nightclubs.” In August 2000, he arranged for Cyril to be flown into the Vetch by helicopter and said Cyril was nearly decapitated by the blades.

“I was shitting myself,” Donne recalls.

Then, Donne says, a stern legal letter arrived from Manchester United after Fred the Red’s tail was stolen in a prank.

In 2001, Swansea City’s economic development chief, Byron Owen, was on vacation in Canada when he opened a newspaper and saw Cyril the Swan waving back at him.

“He’s not just famous in Wales,” Neil McClure admitted to a reporter. “This thing is bigger than all of us.”

McClure wanted out of soccer. On July 12, 2001, he sold Swansea City to Lewis for a single English pound ($1.47). According to Lewis’s memoir, McClure told the new owner that he was “the only person I can trust at the club.” It was billed as an interim measure while Lewis looked for a real buyer with real money because he couldn’t afford to run the club on his own. He soon found it in a consortium of Australian businessmen fronted by a man named Tony Petty. The club was insolvent with debts of $2.5 million, so when Petty arrived, wearing a thin mustache, he tried to fire seven players. The Welsh FA prevented him, but furious Swans fans took to the streets. Lewis feared for his safety.

Things were looking bad for the Swans — and for one swan in particular.

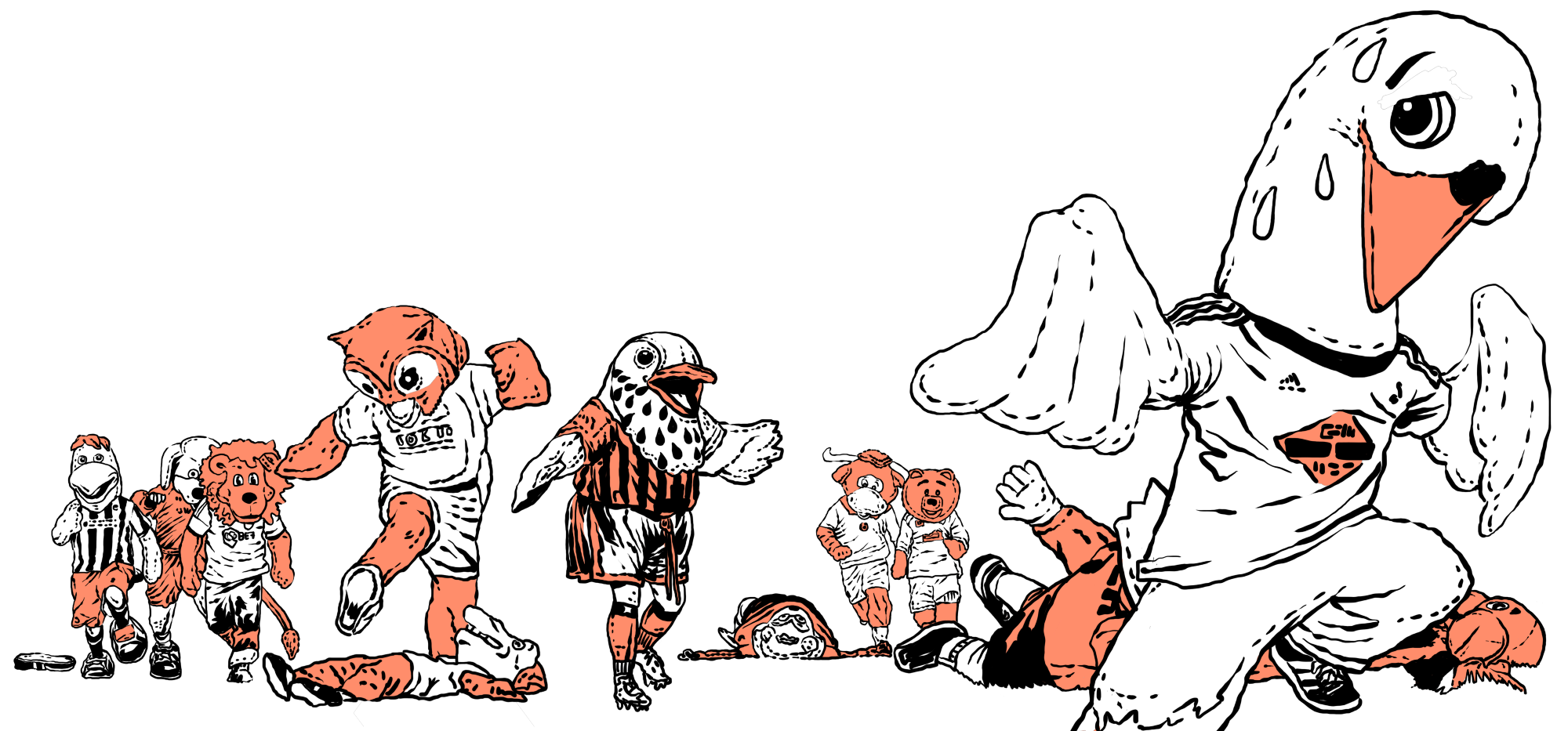

Mascot mania gripped the U.K., and Cyril was its poster bird. By the third annual Mascot Grand National, held on September 30, 2001, at Huntingdon Racecourse, the list of runners had grown from 17 the previous year to 129.

“I was obviously wary about Cyril,” organizer Jim Allen tells me. Allen says he knew the swan had a reputation for being “a bit of a rogue” who was less concerned with winning the race than seeing how many mascots he could “take down.” At the last minute, the BBC decided to televise the race. “They interrupted the Festival of Racing from Ascot,” says Allen. An audience of millions tuned in to see a mascot melee of flying fur and wings, called by a commentator through a fit of laughter. Out in front, one mascot was sprinting to an easy victory. But it wasn’t Cyril.

“You could clearly tell before the race this guy looked like an athlete,” Allen says of Freddie the Fox, who represented the Countryside Appreciation Society. “He was six feet tall and wearing running spikes.”

The race had become a novelty gambling spectacle, and bookmakers across the country quickly dropped Freddie’s odds to 3–1. The mysteriously fleet fox finished meters ahead of the nearest mascot, barely stopping to collect his check. Unmasked as Olympic 400-meter hurdler Matthew Douglas, Freddie was disqualified. Then the real scandal emerged.

A 46-year-old woman wearing a dog costume and representing a Yorkshire club complained that her wrist had been injured after she was pushed over before the race began. “She ran in the race despite the injury and made her complaint to police the next day,” reported WalesOnline. On October 5, a spokeswoman for Cambridgeshire police confirmed that a complaint had been filed: “Cyril the Swan’s name has been mentioned, but the inquiry is still in its very early stages and no one has been arrested.” Donne says injuries weren’t unheard of: Wendy the Wolf of Wolverhampton Wanderers had to be stretchered off, and Watford’s Harry the Hornet suffered two cracked ribs. Donne didn’t recall purposely assaulting anyone. But on December 13, a police cruiser rolled into the Vetch. Officers had reviewed the footage, and Eddie Donne was their prime suspect.

They arrested him on suspicion of actual bodily harm, bundled him into a squad car, and drove him to a nearby police station.

“They read my rights,” he says. “I’d never been arrested in my life! I knew everyone in the police station. All everyone could see was that I assaulted a woman; that’s bad, isn’t it? I’m thinking, Hang on, I have not! ‘Do you want a solicitor? Do you want a lawyer?’ I said, ‘No, because I haven’t done anything!’” Eddie asked why officers took away his sneakers. Were they planning to test them for fibers linking him to Cyril? Negative. “They said people hang themselves with their laces.”

Alone in a police cell for seven hours, Donne realized he was in serious trouble. This wasn’t the Welsh FA’s kangaroo court. “I’m trying to be a groundsman, doing all these hours,” he remembers thinking to himself, but “all they cared about was the swan.” If found guilty, he faced up to five years in prison. Was being Cyril worth it?

Meanwhile, fans were protesting as Swansea City slipped toward extinction for the first time in its 89-year history. Donne’s day job was doomed, and a conviction could leave him unemployable. He had no cash, no hope that a superstar lawyer would save him. Donne’s identity was finally revealed in the press, and the tabloids hounded his family, looking for dirt. “The Mirror called me a Swansea thug,” he says.

Donne spent a stressful Christmas out on bail, but on January 18, 2001, all charges were mysteriously dropped. Perhaps it was a lack of evidence or maybe even luck from above. Miracles were happening as Swansea City somehow dodged its own demise thanks to a consortium of supporters who clubbed together to buy it in the first deal of its kind. After a year under new owner Tony Petty, the fans finally managed to oust him on January 24, 2002, just 24 hours before the club would have collapsed. In a tense meeting in a hotel, they bought the club for one solitary pound, handing it over in pennies. Then, on the last day of the 2002–03 season, the Swans escaped relegation. The next season, Swansea City began to fly up the Football League.

Eddie Donne watched the club grow from inside Cyril’s neck. Added to the Welsh voices in the team huddle were accents from France and Nigeria. An American real estate company replaced the local motorcycle shop on the front of the team’s jerseys. One afternoon, Cyril bent over to moon the home fans and came back up years later in a futuristic stadium with 50-foot video screens. The new Liberty Stadium was a glorious cathedral of concrete and steel, but Eddie didn’t want to work there, not after bulldozers destroyed his beloved Vetch in 2005. Instead, he took a groundskeeping role with the city while remaining Cyril on match days. But times were changing. A family made a legal claim after an incident at the fair left a child with broken glasses. A Dutch television crew asked him to say “Don’t fuck with the Swans!” on camera, which horrified the club. Then Donne fell ill.

On the Mumbles Mile, a Swansea strip popular with locals on a pub crawl, Cyril ran in a charity race in 2005.

“I ended up in hospital,” he says. “I couldn’t catch breath … I wasn’t feeling well. They reckon I was in the costume too long. The dust mites build up.” He was hospitalized for a week after collapsing with a mystery infection, unable to breathe on his own. Donne kept his condition a secret from the club — “I never wanted to blame Cyril” — and the bird didn’t miss a game. “My mates, they covered for me, fair play. They ran round for me, doing Cyril.

“One hundred percent, Cyril got in the way,” he says. “My wife was saying to me, ‘Eddie, you’re missing everything.’” Donne was about to turn 30. He was now married to Rebecca, and they had two children, Thomas and Sophie. He recalls the day. It was at a hospital appearance.

“There was a Christmas party for the children,” he says. “All the lights were on downstairs; all the kids were round the tree. They said, ‘Everyone’s here.’ I said, ‘Hang on now, where is she?’” — the little girl who only smiled for Cyril. He walked upstairs to her ward. She wasn’t there. “I was, like, gone inside,” he whispers. “Imagine that was my own kids? … I’d put the swan first.” Standing by her empty bed, the giant bird bowed his head. Inside, tears were streaming down Eddie Donne’s face.

The end came on March 16, 2007. Donne was no longer a full-time staff member, so Cyril had lost his parking spot. Donne carried the suit half a mile to and from the stadium, and on the day Swansea City played Chesterfield, a steward asked for his security pass. Donne had worked for the club for 14 years, man and boy.

“You know what? Get someone else to do it,” Donne said. He dropped the costume in reception and walked away. “Maybe I wasn’t professional enough,” he says.

Today, Donne rarely watches Swansea matches. He’s been too busy doing dad stuff and studying sports turf management at college. He works most Saturdays as head groundskeeper at the Stebonheath Park stadium, set in the rolling fields of Llanelli, 12 miles northwest of Swansea.

Neil McClure never bought another football club. “Underneath his thick skin I believed there to be a softer side to Neil,” Mike Lewis later wrote. After leaving Swansea City, Lewis became chairman at Exeter City. There he installed spoon-bending magician Uri Geller as vice chairman and the pop star Michael Jackson as an honorary director. But by May 2007, Lewis had left the club $6.6 million in debt and pleaded guilty to fraud. He received a sentence of 200 hours of community service.

According to Swansea City, Cyril is now a “reformed swan,” having married Cybil, a female swan. In 2011, Swansea became the first Welsh club to reach the Premier League, after beating Reading 4–2 at Wembley. The dramatic playoff final was worth a reported $132 million, making Swansea’s one of the greatest rags-to-riches stories in the history of soccer, and the only one involving a giant feathered bird.

The last time I see Eddie Donne, he drives me to the 20,520-seat Liberty Stadium, where Swansea has just defeated Liverpool 3–1 in the Premier League. It is awkward. Like the child of divorced parents at the weekly handoff, I am going to meet the new Cyril. In the gift shop, I purchase a Cyril key ring and a squirty Cyril bath toy. Then, in an empty press room, I am introduced to the man who now plays Cyril, a club employee we’ll call Barry because he has made me promise to keep his identity a secret.

“Cyril is a very one-dimensional character,” Barry says. He pulls the costume from a kit bag, and I notice that inside Cyril’s head there is now an electric fan. “There’s a little pamphlet, a rule book,” Barry explains as he steps into the costume. “They say you should be in the suit for no longer than fifteen minutes.”

Barry asks for Cyril’s giant Swansea shirt, and I silently dress him. I hand him Cyril’s heavy, cumbersome head. When it’s on, the bird is taller than I expected. I am surprised to feel something like starstruck. Cyril the Swan is a symbol of the ingenuity of a doomed community that refused to go quietly. He swooped down from above to save his people, and like all superheroes, he is flawed, his powers a gift and a burden for the man behind the mask.

I am about to ask if Cyril ever reverts to his bad old behavior. But then, suddenly, Barry says he’s lost his security pass. He swings around in a panic, and Cyril brains me hard, beak to face, nearly knocking me off my feet.

Barry is apologetic. “Occupational hazard,” he says in a muffled voice as he continues to search for his badge.

I glance up. Above me, looking down, Cyril the Swan is smiling.

Jeff Maysh is a crime journalist based in Los Angeles. Items from his collection of match-worn Tottenham Hotspur memorabilia are currently on display at England’s National Football Museum. @jeffmaysh · jeffmaysh.com

Elena Gumeniuk is an illustrator and animator who lives in London. Her clients include MTV, Red Bull Music Academy, and SBTV. @elenagumeniuk · elenagumeniuk.com