The radical, racist hooligans of La Familia have attacked other fans, set fire to their own club’s headquarters, and ensured that Beitar Jerusalem remains the only Israeli team never to field an Arab player. But that was before dozens of its members were swept up in a vast sting operation.

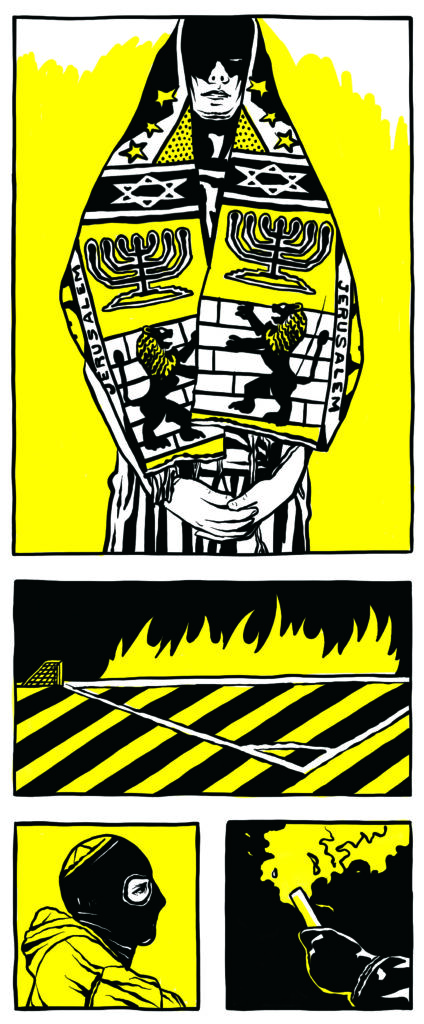

Illustrations by Elena Gumeniak

Editor’s note: This feature appears in the Fall 2017 issue of Howler. Subscribe here.

Fourteen minutes into the match, and in spite of common decency, a prematch PA announcement pleading for fans to keep their genocidal wishes to themselves, and the knowledge that their club would be fined each time they expressed them, the supporters of Beitar Jerusalem had already cycled through several renditions of “We’ll Burn Your Village.” The same announcement is made before every match, and during every match, a thousand or more Beitar fans gleefully ignore it, though Bnei Sakhnin, the opponent on this evening last November and a club supported mostly by Arab Israelis, provided an especially tantalizing target for Beitar’s ardent right-wing followers.

The chanting always emerged from the upper deck of the eastern stand at Teddy Stadium, Beitar’s home ground, and it was a message from La Familia, the group that occupies the section: a warning to the Arabs on the field, a provocation to the hundreds of police officers stationed around Teddy, and a defiant “fuck you” to the front office of its own club, which would be bearing the cost of the fines the chanting would incur.

It got worse in the second half. Shouts of “Terrorist!” greeted Mahmoud Kandil, Sakhnin’s Arab goalkeeper, when he touched the ball. The occasional “Muhammad is dead!” rang out at random moments, and as the game wound down with Sakhnin in the lead, La Familia unleashed the most poisonous phrase in its arsenal, the one it knew would have the most serious consequences: “Mavet La’Aravim!”

“Death to the Arabs!”

All in all, it was a good night, which means there were no fights and nobody went to the hospital. In other words, no outbreaks of balagan, the concept that best encapsulates the unpredictable swirl of menace and malice cultivated by La Familia, explains Idan Strawczynski, who directed a documentary about some fans who left Beitar Jerusalem to form a breakaway club in 2014. It best translates as “chaos,” applicable to situations ranging from romantic relationships in tumult to full-blown riots.

La Familia specializes in weaponizing balagan, and it is this constant threat that is most responsible for the fact that Beitar Jerusalem remains the only team in the Israeli Premier League never to field an Arab player. The group simultaneously organizes around its affiliation with Beitar and seems entirely willing to destroy it with unruly and unlawful behavior rather than see it soften in its anti-Arab identity.

La Familia has essentially taken the club hostage, and its grip has paralyzed a succession of Beitar owners. But where the club has failed, the Israeli state has taken up the challenge. Last July, Israeli police arrested 64 members in a sting operation that resulted in charges of assault, weapons trafficking, and attempted murder. It was the most forceful crackdown on the group to date and the opening of the latest chapter in what has become a battle for soccer’s soul in the world’s holiest city.

Long before the state of Israel was founded in 1948, and more than a dozen years before the first soccer team kicked a ball under the name Beitar Jerusalem, a journalist named Vladimir Jabotinsky set into motion the events that would lead to La Familia’s conflict with Israeli police, Palestinian players, and the Ashkenzi Jews who make up the country’s elite. In 1923, Jabotinsky formed an organization named Beitar to organize Jewish kids around his ideology of Revisionist Zionism and prepare them for the armed struggle he believed Jews would have to undertake in order to carve out a territory for themselves and thus find a degree of safety in a hostile world. But all of this, in a city like Jerusalem, is recent history, so we might as well begin in the spring of 2013, when a man named Dudi Mizrahi set up with some of his La Familia associates outside the home of Itzik Kornfein, Beitar’s general manager and a former goalkeeper who was so popular with fans that they called him Mr. Beitar, and, through a megaphone, threatened to rape his wife and daughters and to commit heinous acts of violence upon Kornfein himself, all for what they called his “Arab love.”

These days, Kornfein works as the city of Jerusalem’s director of sport, and I met him early one morning last fall. He walked into his office at city hall 45 minutes late, apologizing profusely. The Israeli statesman Shimon Peres had died the day before, and Kornfein had been up for hours helping transform Jerusalem’s green spaces into ad hoc helipads for the many world leaders who would be choppering into town. Neither of us mentioned the irony of discussing La Familia, a group known for inciting violence and division, while the country prepared to mourn a man who had won a Nobel Peace Prize for his work on the Oslo Accords, which brokered a peace between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization.

Kornfein is 45, with a buzz cut and faint creases beneath his eyes. Sitting behind his desk, an open window occasionally bringing in the sounds of the nearby tram line, he told me he was 24 when he first arrived at Beitar in 1995 after a few years bouncing between smaller clubs. At Beitar, though, he stuck. Kornfein spent the next 18 years with the club: 12 as its starting goalkeeper (the final six of those as captain) and then, after his retirement in 2007, another six as general manager.

{{Privy:Embed campaign=306930}}

As Kornfein established himself in the net, Israeli soccer and society at large descended into balagan. In 1996, the Palestinian group Hamas was waging a terror campaign throughout Israel in an attempt to disrupt the Oslo process. Frequent bombings made every bus ride feel like a life-or-death gamble. The same year, Hapoel Tayibe, from the West Bank, became the first Arab team to gain promotion into Israel’s top division.

“Beitar fans sang, ‘Death to the Arabs!’ every game that season,” says Gal Karpel, manager of the Kick Racism Out of Israeli Football initiative at the New Israel Fund, a U.S.-based NGO, but matches against Tayibe were among the most vitriolic. At those games, fans chanted, “Muhammad is a son of a bitch!” and “Baruch Goldstein!”—the name of the Jewish right-wing terrorist who massacred 29 Arabs praying at the burial place of Abraham in the West Bank in 1994. In 2002, the segment of Beitar fans behind chants like these came together to form the Lion’s Den, the club’s first ultras group and a precursor to La Familia.

Beitar had fielded a total of two Muslim players since the club was founded in 1936: one from Tajikistan in the late ’80s and another from Albania a decade later. Both had played without issue. Neither was Arab. But in 2004, a year before the official formation of La Familia, Beitar signed defender Ndala Ibrahim on loan from Maccabi Tel Aviv. Ibrahim was a Nigerian Muslim, but something had changed. Throughout his six weeks with the team, he was the subject of intense harassment by fans of the club. “No Muslim or black player should play at Beitar,” he later told the website Sport 5.

As you might expect of a club icon and budding politician, Kornfein spoke warmly of Beitar fans. The hint of a smile formed on his lips as he called it “the club of Israel.” Beitar’s supporters, he said, are “spread out from Eilat in the South to Kiryat Shmona and Metulla in the North.” He disregards the influence of La Familia and the Lion’s Den, calling them “minor,” a sliver of “the 20,000 people at every match.”

Dudi Mizrahi never thought of La Familia as a sliver. Born in Jerusalem to a poor family of immigrants, Jews from Iraqi Kurdistan, Mizrahi went to his first Beitar match in 2002. He was a preteen runaway from the religious boarding school he’d been forced to attend by his parents, both of whom were hobbled by disabilities. He stood outside the stadium begging for shekels until he had enough for a ticket. It was the second year—with three more to go—of the second intifada, the Palestinian uprising in which thousands of civilians and combatants would die.

Mizrahi found solace in the boys and men who had formed the Lion’s Den and would later constitute La Familia. During the intifada, “buses were exploding every Monday and Thursday,” he told me by phone, but Beitar was a constant. When La Familia formed in 2005, he joined up. His upbringing had been full of hardship, but La Familia, he said, “was loyal to one another. Family. Good friends. They help one another. If someone doesn’t have something at home, they help.”

Mizrahi found solace in the boys and men who had formed the Lion’s Den and would later constitute La Familia. During the intifada, “buses were exploding every Monday and Thursday,” he told me by phone, but Beitar was a constant. When La Familia formed in 2005, he joined up. His upbringing had been full of hardship, but La Familia, he said, “was loyal to one another. Family. Good friends. They help one another. If someone doesn’t have something at home, they help.”

As Mizrahi enmeshed himself in the community around Beitar, big changes were taking place at the top. The same year La Familia was founded, the Russian Jewish tycoon Arcadi Gaydamak purchased Beitar from the consortium of Jerusalem businessmen who had kept the club afloat since the 2001 bankruptcy scare. Gaydamak had moved from the U.S.S.R. to France in the 1970s and later made a fortune in the ’90s as an arms trafficker. In 2000, a French court convicted him of selling weapons worth $790 million to Angola’s government, which was under a United Nations embargo. In Israel, he could not be extradited.

When Gaydamak arrived in Israel, he inserted himself into all areas of Israeli society. He funded the Hapoel Jerusalem Basketball Club, donated $400,000 to Bnei Sakhnin, and paid for the construction of tent villages for Israelis fleeing rockets launched by the militant groups Hamas and Hezbollah. And he used Beitar to establish connections with the country’s political right.

You might think La Familia’s extremism relegates Beitar to the fringes of Israeli life, but that is not the case. The current prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, was a vocal supporter of the club for many years, as were two of his predecessors, Ehud Olmert and Ariel Sharon, all members of the conservative Likud Party. Reuven Rivlin, Israel’s current president and also a member of Likud, was chairman of Beitar from 1969 to 1971.

The team has long been “a channel into politics,” says Alon Burstein, a PhD candidate at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem who studies the ideologies of radical groups and is himself a former Beitar supporter. Going to matches at Teddy, he says, is practically a campaign stop.

Long before the formation of a nation-state, Jewish “political parties established many institutions, including sports associations, to advance their ideology,” says Yair Galily, director of research at the Israel Football Association (IFA). Clubs were financed primarily by three groups: Maccabi was founded in 1912 by center-right Zionists; Beitar was started in 1923 by a band of far-right Jews in Latvia; and Hapoel began in 1926, when a faction of Socialists splintered away from Maccabi.

Beitar was the youth movement associated with an ideology called Revisionist Zionism, which held that a Jewish state in Palestine would only be achieved by force. Both were started by a Ukrainian journalist named Vladimir Jabotinsky, who had fought for the British Army during World War I and spent the rest of his life agitating for the formation of Israel. Children who joined Beitar were taught to think of their Jewishness in terms of a nationalist identity and trained for military service. Jabotinsky died in 1940, before the state of Israel became a reality, but his legacy was carried on by Beitar cells that resisted the Nazis in Europe and later the British Army in Palestine.

The modern Likud Party is the inheritor of the ideas of Revisionist Zionism. Beitar Jerusalem won its first major championship in 1976. A year later, Likud won its first national election, bringing Menachem Begin to power as prime minister. Begin had led another Jabotinsky-founded organization, the right-wing paramilitary group known as Irgun, which resisted the British occupation of Palestine and fought for Israeli independence.

These are the links between Beitar’s founding philosophy and the modern conservative movement in Israeli politics that Gaydamak tapped into when he bought the club, but it doesn’t entirely explain why someone like Dudi Mizrahi would choose to make La Familia and Beitar the center of his identity. That connection has more to do with a class divide present since Israel began.

“Mizrahi” is derived from the term Mizrahim, which describes Jews from Arab lands who fled to Israel between 1948 and the late 1960s. The other great bloc of Israelis was the Ashkenazim, Jews of Central and Eastern European origin. The relationship between the two groups can still be tense. Mizrahim tend to feel as though Ashkenazim look down on them as poor, uneducated, and overly religious. For decades, the Ashkenazim dominated Israeli politics and business, but Likud’s rise promised to change that; a vote for Begin was a rejection of this status quo. And with Begin’s connections to Beitar, the soccer club itself became a symbol of political resistance.

Viewed through this historical prism, wherein La Familia serves as an outlet for the frustrations of young Mizrahim, Dudi Mizrahi’s story begins to make sense: a poor, uneducated, and disenfranchised child of immigrants from an Arab-speaking neighbor who gravitated to Beitar, sought comfort in La Familia’s warm embrace, and one day found himself screaming hateful words through a megaphone toward the home of Itzik Kornfein. But Mizrahi was far from alone. There were others who saw La Familia as a vehicle for their own, criminal purposes.

Gaydamak began “shitting money” on Beitar, in the words of Ouriel Daskal, the sports business editor at Israeli news website Calcalist. He spent more than $100 million between 2005 and 2008, according to the daily newspaper Haaretz. Beitar finished third in the Israeli Premier League in his first season. It won back-to-back championships in his next two.

Gaydamak had legitimate business interests in Israel that enabled him to fund Beitar to such an extent, though there were enough irregularities to keep him mired in controversy throughout his time with the club. These issues were firmly on the radar of Israeli law enforcement, which would eventually charge him with money laundering, but they didn’t much concern Beitar fans. They were just happy the team was winning. Upon Kornfein’s retirement in 2007, Gaydamak scored further points by appointing the club legend as general manager. One of Kornfein’s first initiatives was to establish a positive relationship with La Familia. “You want to listen to your crowd,” he explained. “They’re your customers.” Whatever La Familia wanted, like the ability to store its flags inside the stadium—“everything, we gave.” He also helped its members—many in their teens—by interceding with the police when they got into trouble. “They were poor,” he said, “and our fans.”

A 2007 report by TheMarker, an Israeli financial newspaper, revealed the depth of the relationship between Beitar’s ownership and La Familia. It turned out Gaydamak was funneling money to the group for “cheering accessories” and providing transportation to matches. The perks suggest an owner who wanted to placate his most vociferous group of supporters, but they didn’t stop La Familia from flexing its muscle in public. Late in 2005, Gaydamak expressed interest in signing Arab midfielder Abbas Suan, a star at Bnei Sakhnin. When La Familia protested the transfer, he backed down.

In February 2007, Gaydamak launched a political party called Social Justice, and 18 months later, he ran for mayor of Jerusalem, receiving only 3.6 percent of the vote. Soon after, he decamped for Russia, and just in time: in October 2009, he was indicted for money laundering and fraud in absentia.

Kornfein’s relationship with La Familia deteriorated soon after. On March 13, 2010, three members of La Familia entered a Teddy bathroom that was being cleaned by two Arab employees. They locked the door and assaulted the cleaners, ramming their heads into toilets. Afterward, Kornfein met with La Familia’s leaders, hoping that he could convince them to stop the violence. “They went to a certain side,” he said of the outcome, “and I went to another.” That’s when he says he decided to oppose La Familia. It wouldn’t be easy, but the alternative was worse: a future in which Beitar was forever hostage to its most ruthless supporters.

Kornfein’s decision had little effect. If anything, the group seemed to grow even more brazen. Following a Beitar match in March 2012, La Familia stormed a shopping mall across the street from Teddy, chanting, “Muhammad is dead!” while assaulting the mall’s Arab employees. Despite CCTV evidence, the police made no arrests because there was no complaint filed, Kornfein says.

Kornfein threatened to sue the group if the team incurred any damages from La Familia–related incidents, and he convinced a judge to bar some of the group’s highest-profile troublemakers from Teddy, which is public property. La Familia fought back, threatening Kornfein in text messages and phone calls. Members pelted him with stones as he returned to his car from watching the youth team. At matches, they’d curse him with an intensity previously reserved only for Arabs.

The biggest showdown, however, was yet to come. In February 2012, Gaydamak settled his legal troubles in Israel by pleading guilty to a lesser charge and returned to active management later that year. He announced that Beitar would fly to Chechnya to play a midseason friendly against Russian Premier League side Terek Grozny, and a few weeks later came the biggest surprise of all: Beitar would be taking two players on loan from the side—striker Zaur Sadayev, 24, and defender Dzhabrail Kadiyev, 19. Neither player was especially impressive. Sadayev had struggled to crack Grozny’s first team, and Kadiyev hadn’t even made it past the reserves. But the two were unique in another way. They were both Muslim.

The intent behind the deal was murky. In an interview for the 2016 documentary Forever Pure, about the turmoil of Beitar’s 2012–13 season, Gaydamak said he wanted to “show the society for what it really is and expose its own face.” Kornfein said the deal was a dry run for the eventual signing of an Arab player, a move the club hoped would ultimately break La Familia’s influence over Beitar. Others suspected a more personal motivation, says Karpel of the New Israel Fund: the Chechens were part of a business deal Gaydamak had with Grozny’s oligarch owner, Telman Ismailov.

Before the players had even arrived in Jerusalem, La Familia mobilized. It had enjoyed Gaydamak’s spending in the early years, but now it viewed him as a Russian sugar daddy who was destroying the team’s most important feature: its Jewish identity. La Familia became Beitar’s self-appointed defender, willing to damage the club it loved in order to protect it from contamination by Muslims, which would surely lead to Arabs.

At the first match after the announcement, La Familia hoisted a banner in Teddy’s eastern stand that read, “Beitar will be forever pure.” The IFA fined the club 50,000 shekels ($13,000) and closed that section of the stadium for the next five games. Fans like Burstein, the political scientist, who had tickets in the eastern stand were sent to watch from the away section behind one of the goals.

A week later, two members of La Familia torched the team’s practice facility in Bayit Vegan, a neighborhood at the western reaches of Jerusalem. (They were arrested and sentenced to prison terms of 10 and 22 months.) Kornfein was under threat, too. Hundreds of La Familia members protested at practices and outside his home. The team provided a private security detail. The police told him to check underneath his car for explosive devices each morning.

Even so, if the protests were just against him, even outside of his home, he could handle it. What he would not tolerate were threats against his wife and daughters. La Familia crossed that line without blinking an eye.

In 2013, Mizrahi reached the apex of his involvement in La Familia. He had proved his mettle in years past, beating up rival fans, streaking across opponents’ fields, and coordinating group activities, such that he had become one of its most important commanders, a sort of media spokesman.

This is how he came to be leading the protest on the street outside Kornfein’s house on April 3, 2013. Video footage shows maybe 50 members of La Familia standing behind a waist-high barrier across the street from Kornfein’s house, most of them wearing the team’s yellow and black, many in sweatshirts with the club crest and the initials LF printed on the chest, some of them no older than 10. It looks like a normally peaceful neighborhood. Jerusalem spreads out in the valley behind them. Mizrahi is shouting, “Eti Kornfein,” the name of the general manager’s wife, first through cupped hands and then into a megaphone. Everyone around him joins in. Occasionally the ruckus evolves into a call-and-response:

“Eti!”

“Zona [whore]!”

“Eti!”

“Zona!”

“Eti!”

“Zona!”

At one point, the camera zooms in to show the face of an elderly man standing with the aid of a walker, mouth and eyes agape, as he waits at the bus stop that has been engulfed by the hooligans. He totters over and confronts Mizrahi, jabbing his walker into the barrier. The mayhem continues through the afternoon and into the evening, until the protesters are only dimly visible in the light thrown off by the streetlights.

One episode that is not caught on tape but is described in several journalistic accounts of the day involves the use of a blow-up doll as a prop while Mizrahi leads the group in a chant threatening Kornfein’s wife and daughters.

Mizrahi’s actions brought him increased prestige and power inside La Familia and grew his profile on the outside. This is why, in December 2013, he was invited to appear on the Israeli TV program The Newsroom for a segment that brought him into close quarters with Bnei Sakhnin’s Arab forward Mohammad Ghadir. Mizrahi describes his relationship with La Familia during that time with the words “friends, family, identity, love.” On the show, he refused to shake Ghadir’s hand and eyed him suspiciously for the entire interview. At the end, he stormed off the set, calling Ghadir and all Israeli Arabs a “bone in Israel’s throat.”

The Chechens’ four-month loan to Beitar was a disaster. The team won just one of its 14 remaining matches, dropping from fourth place to 10th. Kadiyev played once, as a sub. Sadayev scored one goal in six appearances. (Instead of cheering, La Familia left the stadium in protest.) The experience seemed to exhaust Beitar’s management. The Chechens returned to Grozny at season’s end. Weeks later, Gaydamak sold the team to a new owner who fired Kornfein as part of his plan to move the club in a new direction. These exits emboldened La Familia. As players walked back to the clubhouse at the end of Beitar’s first 2013–14 preseason practice, some La Familia guys threw stones at Beitar’s star Argentine midfielder, Dario Fernandez, and goalkeeper Ariel Harush, an Israeli international, for their past support of the Chechens.

The Chechen experiment also had the effect of further alienating mainstream Beitar fans disgusted by La Familia. Rivlin and Olmert publicly criticized the team, with Olmert announcing a personal boycott until La Familia “was removed.” Team officials estimated that thousands of fans stopped attending matches.

One of those fans was Itsek Alfasi, a mild-mannered lecturer in social psychology at Israel’s College of Management Academic Studies. After La Familia came onto the scene in 2005, Alfasi says he could sense “a more organized group of fans taking control of the stands.” In time, he felt physically threatened, fearful he might say the wrong thing or “look in the eyes of the wrong people.” When La Familia walked out after Sadayev’s goal, Alfasi decided he could take no more. He and some friends “decided to rebuild Beitar the way we believed Beitar should be.” La Familia did this by directing violence toward the club it purported to love; for Alfasi, it meant walking away.

He created a Facebook page prepping for a club whose goal was to be not “just a soccer team, but rather a social change in itself.” Beitar Nordia Jerusalem would be owned by its fans, sign Arab players, disavow racism. He spent a year trying to convince waffling Beitar fans to shift their support to his new team, which would start in Israel’s fifth tier, the country’s lowest. “You try to explain that you’re the re-Beitar,” he says. “But it’s difficult because you’re going from a team playing in the top division and in Europe.”

Ultimately, several hundred people joined him, enough to launch the club in competitive play in August 2014. Amir Shwiki, an Arab player who came up through Beitar Jerusalem’s academy, was one of Nordia’s first signings. The club narrowly missed promotion in its first year but succeeded in its second. The offshoot plays in the same black and yellow and offers free admission to celebrated players from Beitar Jerusalem’s past. This year, Nordia is wearing baby blue and white, the same colors Beitar Jerusalem wore when the club won its first top-division title 30 years ago.

In April, the club won its division and will play next year in Israel’s third tier. Still, some of Nordia’s supporters long for the original.

“Nordia is a means to an end,” member Dan Rotem tells me at a West Jerusalem bar while he smokes the cigarettes his wife forbids in their apartment. If La Familia can be removed from its place at the club, he says, “then the road will be paved for Nordia fans to return to Beitar. I want to be a Beitar Jerusalem fan 100 percent.”

In July 2013, Gaydamak relinquished Beitar Jerusalem to Israeli American businessman Eli Tabib, who assumed the debt Gaydamak left behind totaling more than $3 million. Tabib had grown up in a suburb of Tel Aviv and then moved to Miami in the 1980s, where he became the head of a discount beachwear chain. Though he had a net worth estimated to be in the hundreds of millions, Tabib’s record included faking a passport to flee Israel amid his divorce proceedings, and it’s a wonder the IFA allowed Tabib to take control of Beitar given his track record as owner, first of Hapoel Kfar Saba, which went into administration a year after Tabib sold it in 2009, and then of Hapoel Tel Aviv, which he sold in 2012, leaving behind $8 million in unpaid bills. He had also been indicted for assaulting a young Hapoel Tel Aviv fan who was protesting outside his home.

Still, many Beitar fans were cautiously optimistic about the new owner partly because he was the son of Mizrahi immigrants from Yemen and, ironically, because he had left Hapoel Tel Aviv, a bitter rival, in such bad shape. As Beitar’s owner, Tabib made little effort to counter La Familia. In fact, he developed a rapport with the group. In a 2014 report by the newspaper Yedioth Ahronoth, a senior member of La Familia said that four Familia leaders were responsible for “maintaining constant dialogue with senior management” at the club. Manager Guy Levy signaled to La Familia when, in April 2015, he said that the team shouldn’t bring in an Arab player “because it would create tension and do a lot of damage.”

The IFA continued to levy fines, point deductions, and radius games (home matches a club has to play beyond a specified distance from its own stadium) against Beitar. My research turned up 37 different matches where the actions of La Familia resulted in a punishment for the club during Tabib’s tenure. None of it stopped La Familia from verbally abusing Arab players, throwing projectiles onto the field, and attacking Arabs on the street.

If anything, real-life events seemed to bend to the version of reality the group was trying to create for itself inside the stadium. When, in July 2014, a group of men retaliated for the murders of three Jewish teenagers by abducting and burning to death a Palestinian teenager, an act of violence that would snowball into Israel’s offensive into Gaza that summer, six members of La Familia were among the initial suspects. They were soon dropped from the investigation, but La Familia praised the atrocity, saying it hoped the action would be the “first of many.”

But in July 2015, Tabib changed his tune dramatically. After a Europa League qualifier in Belgium against Royal Charleroi SC, at which traveling Beitar fans flew the flag of Kach, an outlawed Israeli political party-cum-terror group, and threw a smoke grenade onto the field that struck Charleroi’s goalie, the club was fined €95,000 and forced to close part of the Teddy for its next UEFA-sanctioned match. Tabib declared his intention to sell the team and return to the United States, neither of which ended up happening. La Familia, he said, was full of “animals, fucked up and sick in the head.”

On the night of July 26, 2016, four hundred police officers swept across Israel, simultaneously arresting 47 members of La Familia. The following night, the police arrested 17 more. It was the country’s first operation of its kind.

The police had long been familiar with La Familia. But they had always treated the group’s offenses as individual criminal events. This was different—now, the state was linking a group of soccer hooligans with the activities of organized crime. What had changed? Early in October 2015, several members of La Familia were arrested for the attempted murder of a Hapoel Tel Aviv fan who they believed had erased their graffiti, jumping him in a trendy district of Tel Aviv and leaving him with a hammer lodged in his head. He survived, but barely. On October 8, seven hundred people from La Familia and another group, Lehava, which is not affiliated with soccer but preaches an equally anti-Arab message, marched through Jerusalem to protest Palestinian terrorism. A Yedioth Ahronoth report from the night described small posses prowling off the main protest, “scanning” for Arabs to beat up on the street and in shops along the route.

“We really can’t get a moment’s rest these days,” a police officer said. “One event follows another; it’s very sad that so many police officers, including the district commander who came here himself, need to deal with right-wing organizations like La Familia and Lehava instead of combating terrorism.”

The rest of the month saw a new wave of tit-for-tat violence and killings between Israelis and Palestinians, which had many fearing a third intifada. Each day brought new reports of an Israeli soldier being stabbed, shot, or rammed with a car, of casualties among Israeli civilians, and of the violent response by Israeli security forces. The government went so far as to announce a temporary freeze on sensitive soccer matches, which would definitely describe those between Beitar and Sakhnin.

Various branches of Israeli police were also working behind the scenes. They flipped a longtime member of La Familia, code name Judo, in exchange for dropping burglary charges. Judo became a valuable informant, capturing video recordings and text messages over the next six months until prosecutors believed they had enough evidence to cast a wide net over the organization. (As of August 2017, Judo’s identity

remained under seal.) And in the summer of 2016, police moved, arresting 64 people on a litany of prior offenses and conspiracies to commit crimes in the future. Five were suspected in the attack on the Hapoel Tel Aviv fan. Police found a kilogram of explosives, many flares, and more than 20 different kinds of grenades. The individuals were collectively labeled “Hakometz” by the authorities: the Handful.

La Familia remained defiant in the raid’s immediate aftermath. “The leftist media has decided that we’re criminals,” read a note on its Facebook page requesting funds to help cover legal fees. “Sending care packages during wartime, painting the houses of the elderly, filling the homes of sick children with toys,” the note continued. “Is this what makes a criminal organization?”

Many of the suspects were released shortly after the arrests. The attorney Yoni Dadon represented 12 of them, including a minor suspected of taking part in several violent assaults. “About 35 arrestees were claimed to be associated with attempted murder,” he wrote in an e-mail last fall. “In the end, none of them were accused except one person. There is a term in Hebrew which reads ‘the mountain gave birth to a mouse,’ and it perfectly fits this case.” (The Ministry of Justice declined to comment since the case was ongoing. The Court Administration did not respond.)

Two weeks after the raids, the Tel Aviv District Court indicted 18 of the arrested La Familia members, including the minor Dadon was representing, on charges of assault and weapons possession. The defendant Dadon alluded to in his e-mail, Omer Golan, was indicted for attempted murder in the hammer attack. Over the months, prosecutorial intent against the remaining noteworthy offenders clustered around two events: “Florentin,” the Hapoel Tel Aviv–targeted hammer attack, and “Beach Soccer,” a series of planned ambushes of Maccabi Haifa fans.

Golan’s friends began to fall around him. In January 2017, three of his La Familia comrades were convicted for their roles in Florentin and one—the same man who had set fire to the training facility almost four years earlier—for Beach Soccer. Ironically, a chief complaint of the defense lawyers was the reliability of Judo, who, like their clients, had been in La Familia and was accused of serious crimes. Testimony from such a person, Dadon wrote, “is completely unreliable, but in the Israeli legal system it’s acceptable.” This argument gained traction in February 2017, when Judo contradicted in court parts of his original testimony, and prosecutors discovered that he had withheld other recordings made during the course of the investigation. Defense lawyers had hoped the discovery would cement the unreliability of a burglar and soccer hooligan turned state’s witness.

The courts thought otherwise. In early June 2017, the Tel Aviv District Court convicted four more people on charges stemming from Florentin and Beach Soccer.

Golan was among them. In proceedings a month before his verdict, he had sneered at a judge who was part of the “Ashkenazim who control [Israel],” and professed that “even if [he] got 50,000 life sentences [he] will still love Beitar.” Golan accepted a plea bargain for aggravated assault and a possible 20-year prison term instead of attempted murder, which can carry a life sentence.

{{Privy:Embed campaign=306930}}

I went to my first Beitar Jerusalem match on Saturday, October 1, 2016. There was minimal security for this game against Premier League bottom dweller Hapoel Kfar Saba, and I sat on the edge of La Familia in the upper deck of Teddy’s eastern stand. My attempts to speak with its members were rebuffed. (And my later attempts to reach them via Facebook were repeatedly ignored.) La Familia’s section was the only one that was even close to capacity even though members said they were angry at the team. Beitar was 1-3-1 and coming off a 4–0 loss to tiny Hapoel Haifa the past weekend. They punished the players by leaving their banners at home and refusing to clap as Beitar entered the field. They heckled several guys, saying they should play elsewhere.

They still wanted Beitar to win, though, and they sang from the fifth minute on, directed by two leaders standing dangerously on the precipice of the upper deck. “Mikol halev”—Love from the heart—rang out from the section, by far the loudest element in the stadium. The first half was dull save for a handful of wasted Beitar chances and La Familia’s only racist chants of the game. After what I’d heard about La Familia, it almost felt like an afterthought, but 3,500 people shouting, “Burn your village down!” still makes an impression. When they started up another chant referencing a Palestinian neighborhood in East Jerusalem—“Shuafat is burning”—they were immediately shouted down by fans elsewhere in the stadium.

As the second half progressed and the game remained scoreless, it seemed as though Beitar would be conceding points at home to tiny Kfar Saba, and frustration rippled through La Familia. Cries of “benzona” (son of a whore) and “kus emek” (your mother’s cunt) rained down until Beitar midfielder Jesús Rueda knocked a free kick over the wall in the 60th minute. The atmosphere lightened. There was laughter when a couple kids ran onto the field in the match’s dying moments.

But the animosity returned at the final whistle. Beitar players approached the stands to thank the fans. Those in the lower sections clapped. Up where I was sitting, there were nothing but boos and obscene gestures.

A few days earlier, on a warm weekday morning at Bayit Vegan, I had met with Beitar spokesman Oshri Dudai. The scars of the February 2013 clubhouse fire are long gone, replaced by a sleek entry hall with photos of club legends. Dudai said he does not like to sit, so we stood in a parking lot next to the practice field as the morning training session began.

Dudai is stocky, with tips of white in the stubble of his black beard. I knew that in April of that year he had banned a Haaretz journalist, Dor Blech, from the press box for two weeks because the newspaper repeatedly referred to Beitar as the team “that has never had an Arab in its ranks.” In addition to being the club’s mouthpiece, Dudai is a lifelong Beitar supporter, and he believes the club is being made a scapegoat for a problem that is widespread throughout Israel. “You can’t say that this little part of Beitar’s supporters is the only persons or the only community who talk pro-racism or pro-

violence,” he tells me. Singling out Beitar is unfair, he argues, given the “antiracist and antiviolence platform of the team, owner, and management.” Last season, he points out, the back of Beitar’s jerseys read, “Enough with the violence. No to racism.”

Indeed, La Familia’s offensive anti-Arab rhetoric is not unique in Israel. Karpel’s initiative at the New Israel Fund sent anonymous observers to all 240 games of Israel’s Premier League last year. They noted 29 instances of racist chanting or violent conduct from fans of Maccabi Tel Aviv. Yet Beitar Jerusalem was cited 45 times, more than any other club; one of La Familia’s regular chants revels in this, calling Beitar “the most racist team in the league.” And, as Blech tells me, La Familia’s voice is so strong at Beitar’s games that its agenda effectively “becomes the club’s agenda.”

I ask Dudai about the club’s relationship with La Familia after the arrests.

“There is none,” he says. “No official relationship.”

He calls La Familia “an organization of very warm supporters,” which strikes me as very generous given the number of times Dudai has been called upon to answer for the group’s repeated infractions.

“They love the club—and the team—a lot,” he says. “They arrange a very good show almost every single game. There is a part of La Familia who are too extreme, but that part is not typical of the majority of supporters. And of course that’s not part of the agenda of the club.”

The conversation leaves me with more questions than answers—namely, what will it take to solve the problem of La Familia? Governing bodies have fined the club and forced it to play home games at a neutral location. A former general manager barred members of the group from Teddy. Beitar’s owner has repeatedly threatened to sell the team. Israeli police arrested a sizable chunk of La Familia’s members, a subtle shift in strategy from treating La Familia’s offenders as individuals to considering the group’s actions as a form of organized crime.

And yet Dudi Mizrahi’s story seems to suggest that changes of the heart happen human by human. After leading the protest against Kornfein and appearing on the television show in 2013, Mizrahi’s life unraveled. Kornfein sued him over the threats to his wife and daughters in 2014. Mizrahi foolishly paid little attention to the lawsuit, which made it all the more sobering when a court ruled in Kornfein’s favor and awarded $100,000 in damages.

The negative nationwide publicity from his outburst on TV was too much for Mizrahi’s wife, who left him.

“I hurt her with Beitar Jerusalem and put the team in front of her many times,” he tells me.

Unable to pay the damages, Mizrahi once again found himself stationed outside Kornfein’s house, this time begging forgiveness. This was around the time of Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement, lending a special urgency to his plea. Some of his family members joined him; Mizrahi recalls with shame the image of his father groveling on Kornfein’s doorstep. In October 2014, Kornfein reduced the damages to $13,000 and insisted Mizrahi give the money to a charity combating sexual harassment.

The experience humbled Mizrahi, but his transformation wasn’t complete until after the commutation, when he took a job packing dates in a settlement town in the West Bank. He came to know some Palestinians for the first time in his life. And when he discovered that his Arab coworkers earned only a quarter of his salary, he reacted not as a son of La Familia but as a changed man, later posting on Facebook that for “the first time in my life I’d met Arabs and they were not the monsters I had thought.”

Mizrahi apologized in person to Ghadir, the Arab winger he had dissed on TV. He turned his back on La Familia for good, a move that came with repercussions because he still loves Beitar. His former friends have spat on him outside Teddy and threatened to beat him up on several occasions. He spends his days speaking to schoolchildren, encouraging them to avoid his mistakes. He volunteers his time singing to hospitalized Israelis. He watches games from Teddy’s northern stand.

Two months after my visit came the match against Bnei Sakhnin and the filthy chanting from La Familia described in the opening of this story. The club was fined $8,000 and forced to play its next home match at another stadium. By then, Beitar’s poor performances had it hovering just above the Premier League’s bottom seven teams, which were bound for relegation playoffs at season’s end. Tabib promised change. A week later, he announced that he would order the team to walk off the field at any future instance of racism in the stands.

Beitar’s next match, against league-leading Hapoel Beer Sheva, saw just two brief outbreaks of racist chants. La Familia launched into “Here comes the most racist team in the league” as Beitar emerged for warm-ups, and a handful of its members labeled one of Beer Sheva’s Arab players a “sheep fucker.” Beitar’s players did not leave the field. According to Karpel’s game report, both chants were quieted quickly by “their friends in the stands.” In late December, La Familia announced on its Facebook page that it would cease racist chanting to put the scrutiny back on Tabib and the team’s form. It also said it would change the lyrics from “the most racist team” to “most Zionist.”

At the same time, Tabib publicly expressed interest in signing Beitar’s first Arab player. Ramzi Safouri, a 21-year-old Bnei Sakhnin winger, expressed interest in joining the club only to retract it shortly after and apologize on Facebook for even considering such a move. Nonetheless, it seems more likely than ever that Beitar will end its anti-Arab player policy.

“I’d put an Arab going to Beitar right now at one percent,” says Raphael Gellar, a soccer correspondent for the BBC World Service. “A year it ago it was negative 100 percent.”

“Police won’t solve social issues,” says Daskal, the Calcalist editor.

“The problem is that Israel formed a state in 1948, and a lot of Arab land was taken,” says Karpel. “The problem begins with politics, and Beitar is only reflecting what is happening in the country. It didn’t start with Beitar. It didn’t start with soccer.”

Sam Patterson was Howler’s first editorial intern. He still writes occasionally for www.whatahowler.com when his day job in Seattle permits.

Elena Gumeniuk is an illustrator and animator who lives in London. Her clients include MTV, Red Bull Music Academy, and SBTV.

{{Privy:Embed campaign=306930}}