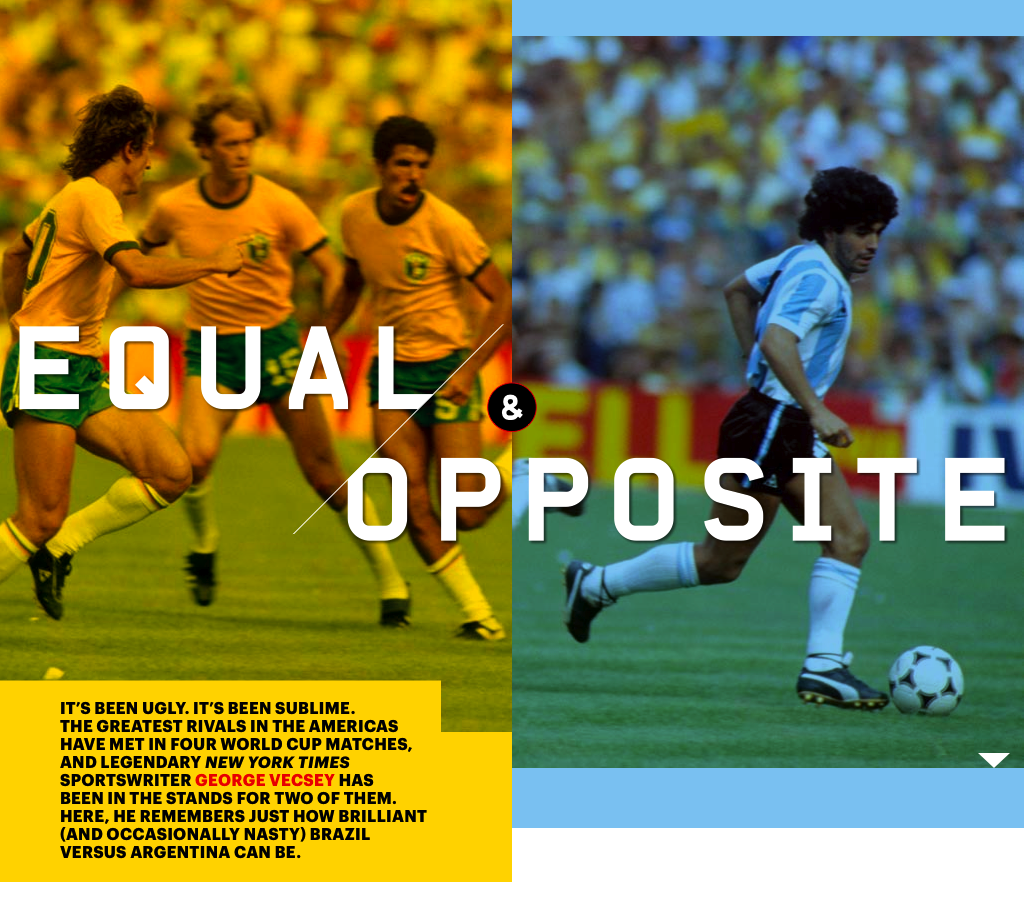

It’s been ugly. It’s been sublime. The greatest rivals in the Americas have met in four World cup matches, and legendary New York Times sports writer George Vecsey has been in the stands for two of them. Here, he remembers just how brilliant (and occasionally nasty) Brazil versus Argentina can be.

By George Vecsey

Note: This story appears in Turnstile, a digital match program for Brazil-Argentina, June 9, at MetLife Stadium in the Meadowlands. Download Turnstile free for your iPad here, or a pdf with the same content here.

[I]t may just be the greatest sporting rivalry of the Americas. The history of Brazil-versus-Argentina includes bristling hostility, long interludes when the two nations refused to play each other, and rumors of a spiked water bottle. It includes a kick in the groin and one of the most gorgeous passes in World Cup history, both administered by one Diego Armando Maradona. The rivalry is always there — in World Cup qualifying rounds, in the Copa América, in the Superclásico de las Américas, the Confederations Cup, and even the occasional friendly.Depending on how one counts obscure cup and friendly matches, Brazil and Argentina have played over 90 times, and are just about dead even. By FIFA’s official count, the two nations have records of 34–24–34 against each other. Those are also Gisele Bündchen’s measurements in inches. (Seriously, hers was the first name that popped up when I typed those soccer numbers into my search engine.) Given Bündchen’s Brazilian citizenship, should Brazil be the favorite when it meets Argentina in this month’s friendly, in New Jersey? Not necessarily. Argentina always has the talent and the flair and the determination to match its South American neighbor when the two play each other. And it would be hard to argue that either team has much of an advantage playing in New Jersey. Admittedly, the Meadowlands is a long way from South America, but it is only a mile or three from Brazilian churrasqueiras and Argentine churrasqarias in the great ethnic metropo- lis of New York City. So welcome home. The uniforms and the flags — the mystical globe of Brazil, the three horizontal bands of blanca y celeste of Argentina — alone suffice to conjure up memories of matches and goals and disputes going back to 1914. There were charges of racial insults toward dark-skinned Brazilian players in the late ’30s, and in 1945 and 1946 two Argentine players had their legs broken by Brazilian players on the field. The bitter feelings stemmed more from soccer bragging rights in the region than international politics — nothing like the so-called Soccer War between El Salvador and Honduras in 1969 — but either way, Argentina and Brazil did not schedule any friendlies and somehow avoided meeting in tournaments from 1946 to 1956. But as the World Cup expanded in size (from 16 teams in 1934 to 32 teams in 1998) and other tournaments grew, it became inevitable that the two most powerful South American teams would meet again. Four of those meetings have been at the World Cup tournament. By good fortune and longevity, I was at two of them, in 1982 and 1990. The first World Cup meeting took place on June 30, 1974, in Hanover, West Germany. Jairzinho of Brazil broke a 1–1 draw in the 49th minute in a second-round match.

https://www.youtube.com/embed/qg3foxKLAts?rel=0https://www.youtube.com/embed/MvK2z6eUbAE?rel=0

The next match in that round came on July 2, when the two South American powers met, with Brazil taking a 3–0 lead late into the game. Driven mad by the score line, and perhaps by Gentile’s tactics in the earlier match, Maradona disgraced himself in the 85th minute, kicking Batista square in the groin, and was expelled from the match. (The Spanish broadcaster commented on the gestos feos — ugly gestures — as he watched the vile kick in replay.) Argentina lost that match, 3–1, and Italy beat Brazil in the final match of the pool and went on to win the World Cup behind Paolo Rossi, who had just been reinstated after his involvement in a gambling scandal.

https://www.youtube.com/embed/LP3u2nDEcPA?rel=0

The next time Brazil and Argentina met in the World Cup was in 1990, in the round of 16 in Italy. Maradona had failed at Barça and moved on to Napoli — and was even more of a marked man because of his infamous Hand of God goal and a magnificent romp through the English defense (voted the World Cup Goal of the Century in 2000) in the 1986 World Cup. His play in that tournament sparked Argentina to a championship over West Germany, but also branded him internationally as an athlete who would do anything, including cheat, to win. Follow that man! was the footy wisdom after 1986. Don’t let him out of your sight! By the 1990 World Cup, Maradona was a folk hero with Napoli — in a city whose civic symbol is the scugnizzo, the tough little street scamp. He was a double villain in the northern half of Italy, where Napoli is considered far below the regional Mason-Dixon line of that culture. (Benvenuto a l’Italia, the banners proclaimed when Maradona’s squad ventured up north: Welcome to Italy.) The fans were waiting for him in the crusty corporate town of Torino, home of Fiat and the Agnelli family and lordly Juventus. Needless to say, the Brazilian defenders were also on the lookout for the stubby scugnizzo, assigning a half-dozen or so defenders to mark Maradona at all times. It was unfortunate that Brazil and Argentina had to meet so early — only a quar- terfinal — and also that the match had fallen into the 5 p.m. slot on a hot day in late June. The Stadio delle Alpi was a bit torpid as these two squads from the southern hemisphere slogged through a scoreless 80 minutes. But in the 81st, Maradona dashed up the middle, drawing at least four defenders. Maradona was no fool — at least, not on the pitch. He did the math, figured that somebody must be loose, and unleashed a brilliant grass-skimming pass that landed at the rapid feet of Claudio Caniggia, who drew out the keeper, made a knowing wide swath to his left, and scored an unimpeded goal. In retrospect, the Brazilian defense made a mistake, but Maradona deserves credit for exploiting it, and Argentina advanced on that goal, ultimately losing to West Germany in a rather negative final.

https://www.youtube.com/embed/3X3p0_R0Y5E?rel=0

The intrigue from that quarterfinal match still lives today. Fifteen years later, Branco, a defender with that Brazilian squad, began advancing the theory that he had been drugged by a water bottle tossed him from the Argentine sideline during an injury break. Maradona, who loves consipiracy theories more than anybody — he once accused Napoli management of cutting a fence to allow thugs into practice to harass its own players during a slump — has at times encouraged Branco’s revisionist lament, probably just to mess with our minds. But would a team really reserve a water bottle with a bit of a sleeping potion, to be tossed to a rival player? Who’s to say it wouldn’t? The hard feelings never go away. At the millennium, FIFA held a contest to choose the best player of the century. By now, Maradona had become something of a caricature due to his drug bust during the 1994 World Cup and his various excesses and political blather. But the world must love a bad boy (the banned Pete Rose was voted onto baseball’s all-century team in 1999), because Maradona won the fans’ electronic vote by a staggering margin. However, FIFA has never seen an inconvenient detail it could not alter or stifle. It convened a “family” panel to select an co-winner, and this time the redoubtable Pelé was chosen. One century, two bests-of. Maradona showed up at the ceremony, collected his hardware, and scooted out of the joint like a man on a counter-attack. Who was the better player? Different roles, different eras, different economics. Pelé never performed for a European club, but he was a phenomenal finisher who in his career scored something like 1,281 goals in 1,363 games, according to FIFA. Maradona, coming along two decades later, had more incentive to migrate to Europe for the big money. He was pursued by crack defenders as well as his own appetites, scoring 292 in 583 matches, and was the great genius of his day, creating goals and obliterating defenses with his rampages. The rivalry between the two men, the two cultures, continues today with new proxies, with Pelé insisting that Neymar of Santos (his old team) could be a bet- ter player than Lionel Messi of Argentina. This verbal competition between the two great Latin players is surely worth exploring: Messi has been part of three Champions League winners for Barcelona but has not yet won a World Cup for Argentina. On the other hand, Neymar is still contractually bound to Santos, and has not yet appeared in the World Cup or European play. At this point, Messi is the more accomplished player but Neymar is only 20, whereas Messi turns 25 on June 24. What happens if Neymar helps Brazil win the 2014 World Cup at home? What happens if Neymar seeks his destiny and makes it with a great club in Europe? What happens if Messi never does win a World Cup? Whatever happens in the short run, it is safe to imagine Neymar and Messi, decades from now, debating the merits of two new prodigies, one Portuguese-speaking, one Spanish-speaking, neither perhaps yet born. But for the moment, it is amusing to listen to Pelé and Maradona debate each other, and even more enjoyable to watch Argentines and Brazilians meet on any pitch, at any time, including in that famous suburb of South America: New Jersey.

George Vecsey, now a contributing sports columnist with the New York Times, has covered eight World Cups, beginning in 1982. We hope he’ll cover a ninth for Howler. He has his own website: georgevecsey.com.