The violence of drug cartels, crooked pols, and dirty cops seeps into the world of Mexican soccer

By Raúl Vilchis Olalde | Photo by Alex Torres

[O]n September 26, 2014, Josué David García Evangelista, nicknamed Little Lefty for his preferred kicking foot, made his professional debut for Club Avispones (Hornets) Chilpancingo of Mexico’s third division. Just 15 years old, Little Lefty played on the left side of midfield as the Hornets beat Iguala FC 3–1.

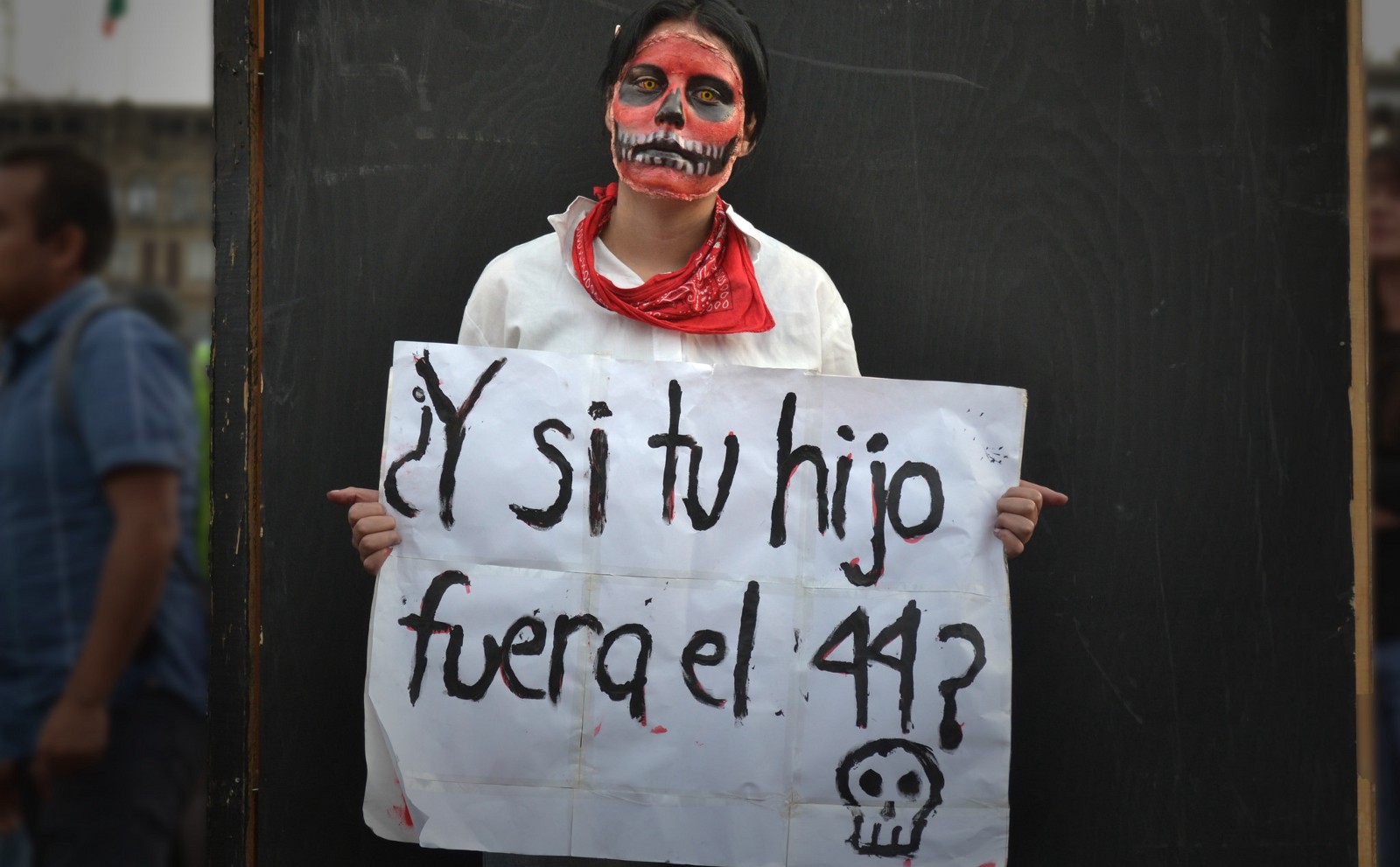

But his first game as a professional would also be his last. Just hours after the victory, Little Lefty became a footnote to the horrors of September 26 — the night that police officers in Iguala took custody of 43 student protestors and allegedly handed them over to a drug gang, who murdered them — when he was shot by municipal police officers working for drug traffickers.

The match ended at 10:30 p.m., and the Hornets were planning to stop in the center of Iguala for a bite to eat before returning to Chilpancingo. But while they were waiting for the referee to prepare an official match report, word came through of a gunfight in Iguala, and the team decided to head straight home.

A series of police roadblocks awaited them on the way out of town, and when the bus driver failed to stop at one of the checkpoints, the police started shooting. A bullet struck the driver in the neck, sending the bus into a ravine. The players lay on the floor as the police kept firing, but Garía Evangelista caught a bullet in the chest and died.

The news of that evening sparked outrage across the country: 43 students from the country’s poorest state kidnapped by the police presumed killed, their bodies incinerated to hide the evidence. But the murder of another six people carried out that night by the police in and around Iguala has received less attention.

Of 292 professional clubs in four divisions (Liga MX, Ascenso MX, and the second and third divisions), 79 play in the most violent municipalities in Mexico.

Iguala mayor José Luis Abarca and his wife, now in custody, are alleged to have links to organized crime. Dozens of police officers have been arrested, and several testified that the mayor ordered the attacks to stop students from commandeering city buses to attend a protest march in Mexico City. That protest was planned to commemorate — of all things — an historic massacre of student activists just days before Mexico hosted the Olympic Games in 1968.

Little Lefty and the Hornets, of course, weren’t looking for protest marches. Just a safe, 90-minute journey south along the mountainous road to Chilpancingo. Investigators later found at least 73 shell casings at the scene of the attack.

• • •

[T]HE MASSACRES IN IGUALA are part of the vicious drug violence that has engulfed Mexico, claiming more than 60,000 lives since the government launched a military campaign to fight the cartels in 2006. But it shows the failure of that campaign in places like Guerrero, where officials are often in cahoots with traffickers and, in a terrifying case like this, can turn corrupt state forces against the population at will.

Even soccer, the nation’s most beloved pastime, is not safe in Mexico.

Last month, the website JuanFútbol.com analyzed data from the national soccer federation, Femexfut, as well as the Interior Ministry, and found that out of 292 professional clubs in four divisions (Liga MX, Ascenso MX, and the second and third divisions), 79 play in the most violent municipalities in Mexico.

In 2001, British street artist Banksy visited a Zapatista-controlled town in Chiapas and painted a mural with a hopeful message: “Freedom through football.”

Little Lefty is far from the only player affected. In January 2010, Paraguayan national team star Salvador Cabañas, who played for Club America, was shot in the head at a Mexico City nightclub by a cartel hit man. He survived and later returned to the field, but he was never the same player.

In August 2011, a Liga MX game between Santos Laguna and the Morelia Monarchs was interrupted by a shootout between police and drug traffickers outside the stadium. The shots were heard on the live TV broadcast, which captured the players running to the locker room tunnels and the fans hiding under the bleachers.

In his book This Love Is Not For Cowards, Robert Andrew Powell tells the story of the Indios of Ciudad Juarez. Back when that city was considered the murder capital of the world, players routinely suffered death threats and lived in fear.

The violence in Mexico has arisen in part from the Mexican government’s failure to address deep-seated problems of poverty, inequality and corruption, and the massacre in Iguala shows just how little has changed in the past two decades regarding the repression of the country’s disenfranchised citizens. Back in 1997, paramilitaries gunned down 45 members of the pacifist society Las Abejas (“The Bees”) as they prayed at a church in the town of Acteal. Las Abejas had shown support for the Zapatistas, a revolutionary political and militant group.

Fourteen years later, in 2001, British street artist Banksy visited a Zapatista-controlled town in Chiapas and painted a mural with a hopeful message: “Freedom through football.” But there can be no freedom through football in Mexico when the players are ducking bullets, too.

Raúl Vilchis Olalde is a freelance writer from Mexico City. He lives in Brooklyn and tweets under the handle @elvilchisolalde.