As the sport becomes less constrained by geography, even nonleague clubs are transforming into global brands. With an active online presence and a growing fanbase of supporters around the world, Hashtag United are showing themselves to be ahead of the curve.

The invention of the smartphone has made many aspects of modern life easier. Working as a steward at football matches in the UK is not one of them.

Stopping a fan from rushing onto the field to take a selfie with Lionel Messi is, however, a more straightforward task than stopping a fan from filming the match itself on a device. Companies paying to broadcast blockbuster football matches expect exclusivity, a prospect at the foundation of the sport’s dizzying new financial heights. At the opposite end of the spectrum, the bottom of the English football pyramid, you wouldn’t expect to find similar restrictions when it comes to filming matches.

Cole’s Park in North London is home to a pair of non-league teams in the 9th and 10th level of English football. It’s lone stand is weathered and can seat just under 300 spectators. The pitch’s artificial surface can withstand use from multiple teams and is perhaps the most advanced technology the ground has to offer.

The small stadium is parked on White Hart Lane, geographically close and financially distant to Tottenham Hotspur Football Club, yet you are likely to find a similar matchday ban on filming the action on the field. Hashtag United, one of the ground’s two home teams, will be lucky to have a hundred supporters turn up in-person for their next home match. But hundreds of thousands of fans will watch the game online just a few days later.

The team’s appeal is curious to those watching in real life. The level of play is far from exceptional. There isn’t the backing of a rich investor luring fans through a renovated clubhouse. A tidy kit sponsor via the popular video game Football Manager and strange name are the only noticeable giveaways that Hashtag is up to something. The catch to their popularity is present on the internet, based on the idea, more or less, that there is no catch.

In 2015, Sport England estimated that some 8.2 million people participated in playing football in the country, about one in every seven people. Though the Premier League draws the most eyeballs to the game, the majority of the sport’s competition takes place at the amateur level. Sunday League–named for its singular, universal day of play–is a grade of competition that sprawls through the country, where hangovers are as likely to keep players sidelined as bobbly pitches.

Like most aspects of modern culture, the community has a thriving presence online. A growing panel of content creators have taken to sharing their weekly football journey at the Sunday League level, broadcasting to a substantial audience. In exchange for watching a slightly butchered version of the beautiful game, viewers are allowed ride-along access knitted within social media.

https://twitter.com/sedonsfc/status/1043860857871052800

Palmers FC, one of YouTube’s founding Sunday League channels, began recording matches for their own enjoyment to watch back goals and memorable moments. Popular videos on the channel often include extra-curricular caveats from off the pitch. A video showcasing their match against local rivals Aveley Stags not only shows highlights of the game, but photos of the team’s previous night out at a charity quiz event and splices of team captains drunkenly crashing a 21st birthday party. Longtime viewers of Palmers might feel closer and more knowledgeable of the club’s all-time leading goalscorer Nick (aka “Magic Boots”) via the Sunday League-style videos than professional footballers whose social media and press interactions are filtered to a droll level of engagement that rarely registers online.

SE Dons, a South London Sunday League team, is one of the community’s most spirited channels, diverse and outwardly passionate in a manner that often sees them reprimanded by league officials for everything from player registrations to exuberant celebrations. Viewers are either die-hard “anything for the dons” supporters or staunchly opposed–few opinions fall somewhere in-between.

The team’s captain and fan-favorite, George “Big G” Kamursai, is known for his imposing stature. “My keeper’s 6’6” and Ugandan” is the sideline call whenever he cleans out an opposing striker. His bulwark on the field is offset by emotional and humble team talks off it. When the Dons uploaded their cup final match against FC Cortez to conclude last season, the video included footage of Andrew, the channel’s manager, speaking at his mother’s funeral two weeks prior about her love for the club and the forthcoming match.

The videos are relatable and accessible to the average football fan in-tune with social media. When a club welcomes a mild spotlight of internet fame to their campaign, success online depends on being able to showcase the aspects that make Sunday League YouTube-worthy: sideline banter, leg-breaking tackles and seasons ending with silverware. The matches are translated through a mix of video blogging and sports broadcasting, often boiled down to a 20 minute highlight reel.

Earlier this year, an amateur boxing fight between UK YouTubers KSIolajidebt and Joe Weller reportedly drew more live viewers than last year’s FA Cup final. In the early days of Sunday League YouTube, the community grew of similarly staged prize matches, led by the FIFA video game community which KSI and Weller also belong to. Spencer Owen, whose personal channel hosts just under 2 million subscribers, was able to spark his Sunday League journey through exhibitions in the Wembley Cup, competing against other high-profile YouTubers.

Bolstered by his status in the FIFA community, Owen’s team, Hashtag United, quickly rose to the top of the Sunday League scene. Because their campaign mostly consisted of blockbuster friendlies against YouTubers and teams put together by the likes of Sky Sports and Google, the club tallied “league” points in a casual format inspired by FIFA’s multiplayer ladder opposed to a long, organized Sunday League season. Last year, Hashtag hosted a highly-anticipated friendly against Palmers which brought together opposite ends of the community, each with their own interpretation of the Sunday League spirit.

Like most evenly played football matches, the result hinged on a handful of close refereeing decisions and small chances by either side. Because two versions of the same game emerged, each through a different editor’s lens, the social media battle between supporters was especially toxic. Through Instagram stories, YouTube comments and Tweets, controversy around the result (a 2-1 victory for Hashtag) raged on like any debate heard on sports radio or digested on pundit television. Defined not by a level of play but likeness to the sport’s professional atmosphere, the Sunday League scene had now firmly arrived.

Perhaps incited by digs at their lack of authenticity to grassroots football, in combination with a rapidly growing audience, Hashtag United broke free from the confines of Sunday League and joined the English Football Pyramid in the 10th level of play for the 2018/2019 season.

In as little as nine years, Hashtag could theoretically find themselves strolling into Old Trafford against Manchester United for a league match. While such a climb out of the pyramid’s basement is rare, the pressurized ladder is prone to magic even in modern times. In the span it would take Hashtag to claw into the Premier League, Bournemouth surged from the edge of extinction in League 2, to sitting comfortably top-half in the Premier League. Lest we forget Jamie Vardy’s recent journey from the National League (fifth level) with Fleetwood Town to record-setting, Premier League champion in the space of four years.

Perhaps the clearest, high-profile blueprint Hashtag could hope to replicate would be that of AFC Wimbledon, a club who journeyed from the Premier Division of the Combined Counties League (ninth level) to League 1 (third level) in little over a decade’s time. This journey began in the wake of the predecessor organization, Wimbledon FC, moving to Milton Keynes and rebranding itself as MK Dons.

Hashtag is currently sat near the top of Division One of the Eastern Counties League (10th level). Promotion this year would see them into the Premier Division of the Eastern Counties League (ninth level) and so on through the non-league system. The club is managed by Jay “Devs” Devereux, who previously coached in the National League South (sixth level) only two steps below league football, the promise land (or exit door, depending on direction) of full-time, professional football.

In the modern era of the sport, where tech giants are vying for a piece of the pie, it may not be far-fetched to view an established digital footprint as the framework to a successful football club. In a futuristic, albeit mildly dystopian, world where social media performance translates directly to success on the field, Hashtag would make quick work of the pyramid.

The average non-league club offers varying degrees of digital outreach in their social media department. While a successful social media campaign may save a tech startup, the free market levers of the football pyramid traditionally dictate a club’s size and prospective growth; the higher they climb, the more visible they become, the more fans they have, the higher profit they can turn, and so on. Social media could be used as an avenue to attract supporters and sponsors in a fraction of the time it takes for a team to claw their way up the ladder.

For example, a handful of SE Dons players also compete in the Isthmian League Division One South East (eighth level) with Hythe Town FC. The club’s Twitter account sees a spike in interaction when a Dons player is mentioned (the club also uploads high-quality highlights from their matches on a website that appears to have been constructed around the time the club was formed in 1992) and has slowly begun to outpace clubs of similar age in their division, sporting close to 6,000 followers on Twitter.

One non-league club whose fan base has achieved notoriety recently is Dulwich Hamlet, a club that has spent most of their history in the Isthmian League Premier Division (seventh level). By way of its anti-racist, LGBTQ-positive, left-leaning philosophies, Dulwich has amassed a loyal following on social media. With now over 20,000 followers on Twitter, the club was promoted last season to the National League South, the first time it has progressed above the Isthmian League in 111 years.

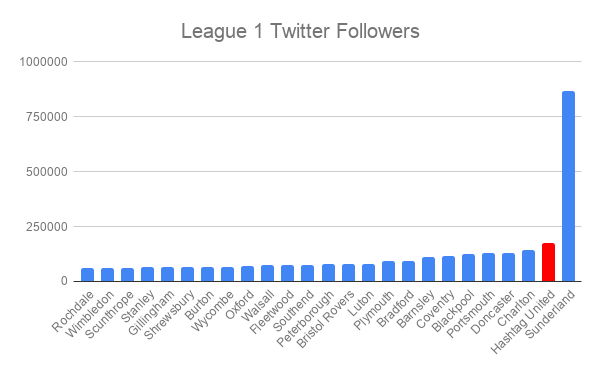

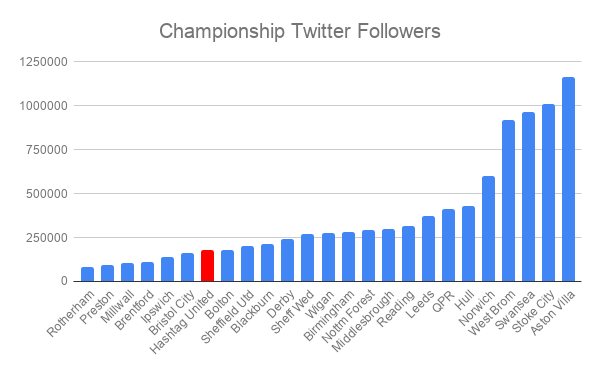

If Hashtag United were placed on the pyramid based solely on the size of their social media presence (over 176,000 followers on Twitter) they would likely land somewhere between League One and the Championship (level two). The median following for clubs currently in League One is around 77,000 followers (the league’s average of 119,000 followers is slightly inflated by Sunderland’s outlier count of almost 900,000 followers). The average Championship side has about 380,000 followers, with the smallest being Rotherham United at 82,000 followers.

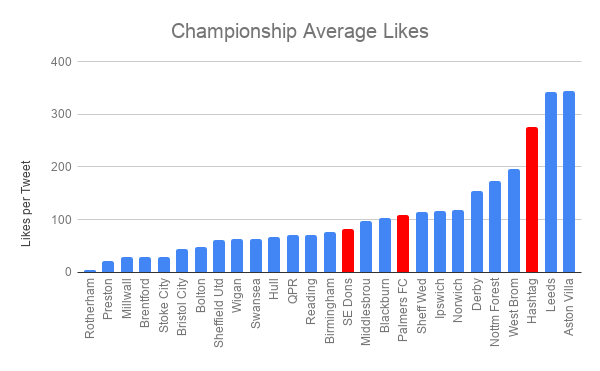

If loyalty (which might more directly translate to monetary value for a club), rather than size of social media fanbases, was a predictor for success, Hashtag would firmly find themselves in the Championship. According to the social media analytics website SocialBlade, Hashtag’s tweets receive 277 likes on average, more than double the average amount for a current Championship organization and higher than a club like West Brom, who have more than 900,000 followers. Even the exclusively Sunday League sides of Palmers and SE Dons would find themselves at home in the Championship based off Twitter interaction, as they receive on average 109 and 82 average likes respectively, on par with Middlesbrough who have an average of 92.

Even the most technologically-inclined football fans are probably thankful that likes and retweets aren’t currently the basis for prosperity in the sport. Fans of non-league and clubs outside of the financially flush pinnacle of the pyramid tend to seek out smaller sides in an effort to avoid the glitz and ego at the top.

But many non-league clubs would likely fold if it were not for the Saturday afternoon TV blackout of Premier League matches which encourages fans to the paying gates of local sides. While streaming and pirating weakens the effect of the blackout, the internet might be able to offer new avenues for clubs with storied histories, those built into the cornerstones of communities that still find themselves teetering on the brink of financial ruin. That is, if they are willing to embrace the change.

At a recent league fixture, Hashtag United let an early 1-0 lead slip against Coggeshall United, a team in their second season of non-league football. After dominating the early stages of the match, Coggeshall answered with a pair of quick goals and Hashtag found themselves down 2-1 at the halftime whistle.

“If you want the good stuff that comes from playing for this football club, you’ve got to work for it,” Devereux, a grisly middle-aged Englishman, explained to his players, furiously rocking back and forth, ready to vomit onto the physio table in the center of the changing room.

“If we don’t win this game and I so much as see a selfie or an Instagram, I’ll tell you now, I’ll go around and I will volley every (expletive) phone in this room to bits.”

The players were still as Devs prepared to lead the team back out onto the field. Before he could locate the handle on the door behind him and see his way out, the sharp, familiar PING! of an iPhone notification broke the room’s nervous silence.

The team came back to win 3-2.

Robert Kelly is a freelance journalist whose work appears in The Guardian, Bleacher Report, GQ, Billboard, and more. You can follow him on Twitter @RobbyKelly7.

Contributors

Robert Kelly