It’s near the end of a three-hour interview and Tony Bono quietly acknowledges a painful truth. “I came out 18 years ago, and I am still coming out today,” Bono says. “It can be exhausting because you never know how people are going to react.”

Tony Bono was a star of the interregnum—those wilderness years in between the North American Soccer League and Major League Soccer, when first-team All-Americans were happy to play in leagues like the Lone Star Soccer Alliance and the American Indoor Soccer Association.

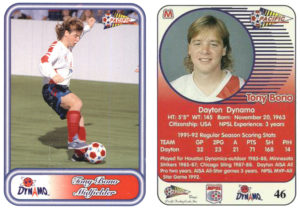

Many American soccer fans from that era recognize Bono most prominently from his days with the Dayton Dynamo of the AISA and then the National Professional Soccer League from 1988-1995; he was the Most Valuable Player of the 1992 NPSL All Star Game. But it wasn’t easy.

The Pennsylvania All-State high school player out of Philadelphia’s Frankford High earned All-American status at Drexel University in 1984. He was drafted by the Minnesota Strikers of the Major Indoor Soccer League in 1985.

Soccer has been a staple in Bono’s life from a young age. His first memories of soccer involved his father and Philadelphia’s Lighthouse Boys Club.

“My dad was very influential in my soccer journey. He was a very good player,” Bono says. “He could have gone further professionally as several of his friends did, but he chose to get married and have a family. He was a really good coach and coached my older brother’s team. My sister also played on one of the better teams in the state and my mom also coached.”

With his dad coaching an older age group, Bono played for a Scottish international at Lighthouse named Jimmy Mills. Mills coached the U.S. Olympic team in 1956 and spent 20 years at Lighthouse, taking numerous squads to city championships and winning multiple national titles.

“He was an amazing coach for basics and we did so many drills that were not the norm of the day,” Bono said. “There was a lot of footwork. We were always moving with the ball. We always had the ball at our feet. We did not win a game the first year I played, when I was six. We were 0-and-whatever; I mean, we were really horrible. But we played in the league cup and won and started becoming one of the better teams regularly in the state.”

Like many industrial and port cities in Europe, Philadelphia fostered a deep-rooted soccer community—despite being embedded in a region that was infatuated with American football. Bono grew up in an area with a series of streets that made up a square. In the middle resided a big park.

“Everyone in the square played soccer. That’s what you did to fit in,” he says. “There were some really good players just in this neighborhood. You could go out any time after school and there was a soccer game going on. We were playing against older kids—if a game didn’t break out in a fight, it wasn’t a game.”

Philadelphia’s ethnic segregation meant that Bono’s teams would welcome Hungarian, German and Ukrainian teams to Lighthouse for some tough games.

Bono was talented enough to make Frankford’s varsity as a sophomore. He played sparingly the first couple of games, but substituted for an injured starter around the third contest, scored a couple goals, and never relinquished his spot. He also competed in the public league championships for diving and finished two years of gymnastics before heading to Drexel.

“I made sacrifices in high school. I didn’t par! for the most part. On Fridays and Saturdays, I chalked a goal on a local factory wall and had targets within the goal. I wouldn’t go home until I had hit 50 in each box with the ball. One night, I was walked home by the police because I was out after curfew and the neighbors kept hearing the banging sound against the wall.” High school is also when Bono said he knew.

“I realized I was different, but I wasn’t going to succumb to being different. I was going to be like everyone else,” Bono says. “I never wanted to say I was gay, and nobody knew. It was pretty difficult. Looking back, I think that is one of the reasons why I worked so hard at soccer—so I could leave town and nobody had to find out at home.”

Although he was a good scorer and an even better playmaker, Bono often played other positions, including outside midfielder. That was the case early at Drexel, before Bono was slotted in at center mid and did some real damage. “The big team in our area at the time was Philadelphia Textile. They had some good players and they went to the Final Four. That’s the school I wanted to go to, but they didn’t even look at me because I was 5-foot-3. Barry Barto, the coach, said I was too small to play.”

Bono proved Barto and other doubters wrong at Drexel. The Dragons were East Coast Conference giants in the early 1980s, winning two ECC crowns and a Soccer Seven title during Bono’s playing days. He earned numerous accolades and was named Division I First Team All-American as a senior, Drexel’s first. The school inducted Bono into its Hall of Fame in 2004 and his retired jersey now hangs from the rafters in Drexel’s Daskalakis Athletic Center.

His professional career began in the summer of 1985. He was drafted by the Minnesota Strikers of the Major Indoor Soccer League, but started in Houston, where a team called the Dynamos was hoping that a new outdoor league would emerge from the North American Soccer League’s recent demise. The Dynamos played an international exhibition schedule that summer featuring the likes of Sheffield United, the U.S. National Team and the Black Lions of Guadalajara.

Bono headed to Minnesota that fall, although he continued to play outdoors with Houston the next couple of years as well. After making more than 50 appearances over three seasons with the Strikers—and even partying at Prince’s First Avenue club—he joined the Chicago Sting before leaving the MISL and joining the AISA’s Dayton Dynamo in the fall of 1988.

Throughout this time, Bono lived a life set apart from the one that would make him happiest. “I don’t want to sugarcoat anything because it was not easy. Guys were always going places with their wives and their girlfriends. I met a girl on the Strikers’ dance team and we went out and started to date and then I couldn’t go any farther—I didn’t want it to go any farther,” Bono says. “She dumped me and went out with another guy on the team. I had to watch guys on the road hook up and it was insane. As the young guy on the team who wasn’t attached, everyone was trying to set me up and I had to lie and tell them I had a girl back home.”

While playing in Houston in the summer of 1986, Bono met a young woman, the sister of a soccer-playing friend from Philadelphia. They spent all night talking when they first met and became serious very quickly.

“We exchanged promise rings in a ceremony and I considered her my fiancé,” Bono said. We carried on a long-distance relationship through Minnesota, Houston and Chicago. She was the one true female love I had, and if I could have figured out a way to make it work, I would have.” Bono regrets how the relationship ended, with him pushing her away with his actions instead of admitting to her that he was gay.

“I treated her horribly. I was an asshole,” Bono said. “I regret it to this day.” When Bono arrived in Dayton, life became even more difficult.

“I always knew people were looking at me—predominantly in Dayton. I was the captain of the team from the time I was there until the time I left. I served as interim coach on two different occasions and I was the director of community relations, so I was one of the most recognizable people in Dayton. It was really, really difficult. But I did date. I was with a few women. I still tried to conform, even though I knew I was gay. I stopped because I knew I couldn’t do this to other women or myself anymore.”

The midfielder is humble when discussing his career and accolades, even while relaying stories tied to all the jerseys he has on display in his suburban Maryland home. And even when his husband, Al Risdorfer, talks him up as “a great soccer player.”

His soccer journey is full of the ups and downs commonly associated with navigating and surviving a professional career. But they pale in comparison to Bono’s personal voyage the past few decades.

Bono’s story comes to light thanks to yet another standout performance, this time at the 2019 Sin City Soccer Classic International Gay and Lesbian Football Association (IGLFA) Indoor World Championship. He played for the Minnesota Gray Ducks, which sent two teams to the tournament in Las Vegas in January.

According to Ryan Adams, goalkeeper for the Gray Ducks I team and one of the team’s organizers, the games at the tournament are short and sweet.

“There are two divisions of 12 teams, and Division I is super competitive,” Adams says. “We’ve been there a few years and the difference this year is we had more depth. One team was composed primarily of younger players; the other team was former tournament guys. After the first day, we had the first and third seeds.”

The second team, an older squad talented enough to play in the top division, featured Bono. Now in his mid-50s, he quickly became a leader for the team, which sprung an upset on the first Ducks team early in the double elimination semifinals. Adams’ younger squad prevailed in the final as the Minnesota teams went 1-2.

At the end of the tournament came an announcement: “The MVP of this year’s Sin City Classic Division I, from the Minnesota Gray Ducks II team is…Tony Bono!”

Bono was incredulous. “I had no idea they handed out MVPs, so when the announcement was made, I just said ‘what?’ I helped our team get to where we were, but there were better players.” Bono says this with a slight smile, careful not to reveal just how great it felt to play good soccer in an environment that felt like home.

“Tony was really hesitant at first, but he bucked up and listened to his trusted friends,” Adams says. “He had beautiful footwork and he was the key to his team’s success. I hope I can play like him when I’m over 50.”

Bono had a relationship that did last a few weeks with a prominent member of the Dayton LGBT community, but even then, his isolation spoke volumes. “Back then, groups of people could come out and meet the team at a bar or restaurant after a game,” he says. “There was a whole table with gay men and I always made sure that I went to that table. It was my chance to just see and talk to other gay guys. But mostly, I would just drive around the gay bars and watch people coming out, just so I could see what they looked like. I wanted to experience it, even if it was only an hour or two hours.

“I would drive an hour and 45 minutes to spend two hours in a bar just to be around people. I didn’t even drink. I went into the bars and pulled my baseball cap down low. People would ask me my name and I would say ‘Bob,’ ‘Vince,’ ‘Jim.’ I never told people my real name. It was never easy and actually quite scary because there was always that chance that someone would see me or notice me.”

Those kinds of encounters did occur, forcing Bono to think quickly. His personal life was full of situations like these. The isolation, the loneliness…and the drives.

“A lot of times in Dayton, when we went out on the road, we drove vans, and I was always one of the van drivers. I wanted the keys so I could go out. I would find the gay bars in the city we were in and I would just circle them. It was very lonely.”

Bono set up a charity in Dayton called Tony’s Tykes that helped pediatric AIDS patients and their families.

“One of my good friends worked at Children’s Hospital and she told me that there were some kids there with HIV that were not going to have a Christmas. Their families just could not afford it, and she asked if I could help out. This was my chance to get in and help without coming out. We started off with four families the first year and then we ended up with sixty-something families a few years later, which was both good and very sad.”

At the tail end of his time in Dayton, Bono experienced an epiphany and found his soulmate. Bono was struggling under new coach Terry Nicholl even though he was named to the All-Star game in St. Louis. There was a two-week break around the game, so Bono flew out to San Francisco for the first time. The experience was a breath of fresh air.

“I was walking down the streets in San Francisco. I was in the Castro, the center of the gay universe, and just walking the streets and I thought it was amazing. They get to live out in the open and be happy. After that, I came back and I was really rejuvenated and refreshed and I had the best second part of the season.”

In 1994, Bono met his future partner and now husband, Al, in a bar in Philadelphia, embarking on a prolonged long-distance relationship.

“We would see each other during the summers and whenever we could, like a long weekend,” Bono says. “When we came into Baltimore, he would stay in the same hotel. I would spend the night with him and the guys thought I stayed out all night with somebody and now I could laugh and say, ‘Yeah, I did.’

“In Dayton, he would stay about 30 minutes outside the city where people didn’t know who I was. It was kind of exciting, but I was also somewhat bitter that we had to go about it that way. I felt badly for him because he didn’t sign up for what I was going through.”

Al was instrumental in Bono’s transition from soccer to regular daily life. Although he graduated with a degree in marketing from Drexel, Bono admits that he fell into a spiral after leaving an assistant coaching opportunity with the Philadelphia Kixx in 1997.

“I went from a professional soccer player to a nobody. I wouldn’t leave my apartment, which was a problem because the Kixx wanted me out of that apartment,” Bono says. “I moved back in with my mom and dad. Then they moved to the Cape May area and I moved in with my brother. Then…all hell broke loose.”

“I came out to my family overall in 2001,” Bono says. “I remember perfectly because the first important date was September 10, 2001. I went to London that summer with a gay soccer team for the Gay World Championships and won the bronze medal over there. I got to be a part of a gay community that I never knew existed. It was phenomenal. I told my family I was going over to England, but I didn’t say why or with who.

“One of the guys I played with was also a soccer referee in Philadelphia. Either he or his partner outed me. On Monday morning, the tenth, a friend called and asked, ‘Are you gay?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’ Like many people when they found out, he asked why I hadn’t told him.

“I was so angry that I was outed and my life changed because of the referee or his partner. It was for the better, but I was angry at that time that I didn’t get to do this on my own terms.”

Bono was scared. His father was still a very prominent figure in the Philadelphia soccer community.

“I was trying to figure out how to tell my parents. They were now living in New Jersey, 90 minutes away. I called to see if I could come down and they asked me what was wrong.”

The next day was September 11, and, as Bono says, “Now me being gay does not matter.”

Bono did go down to the Cape shortly thereafter. “It was so freaking tense because they knew I had something to tell them, and I was scared to death. We sat down after dinner and I reiterated to them that I went to London to play in a soccer tournament the previous summer.”

“Yeah,” Bono’s parents said.

“A gay soccer tournament,” Bono said. “I’m gay.”

Bono’s dad, who has since passed away, looked at his son and gave him a response that warms his heart to this day. “How did you guys do?”

“My dad was a truck driver, as blue-collar as they come,” Bono said. “I thought he would come unglued. When he said that, I thought it was amazing.”

Bono’s mother cried at first and asked what she did wrong. But her support for her son was as unwavering as Bono’s father’s.

The crazy thing? They both knew. And they both knew separately, without telling each other. Bono’s father had been doing some work in the house when Tony was living there and found a card from Al that said, “I love you.” He’d quietly put the card back and had never mentioned it. Bono’s mother had found a receipt from a gay bookstore in Philadelphia.

“I told her, ‘I wish you had said something to me about it, because I was actually there to get a book on coming out,’” Bono says with a smile.

“There was still a lot of tension because I had to face my friends. I was playing in leagues and every time I went onto the field, I wondered who knew and how was I going to handle what they said. When I told my sister, on the boardwalk in Wildwood, New Jersey, she said, ‘Yeah, I know. When are we going to get ice cream?’ She knew Al was my partner.”

Bono says he can count how many friends he lost on one hand, but the encounter he had with his brother, Russ, was the toughest.

“My brother is a big deal. I was living with him after I stopped playing professionally and I wanted to be respect’l of him. He asked me point blank, and not in a nice way, if I was gay. When I told him, ‘Yes,’ he kicked me out. The next day, he called and apologized, but we didn’t talk for about a year. I didn’t go back, obviously.” Bono describes the encounter as “nasty.”

“Today, we’re good. I tried to put myself in his shoes,” Bono says. “It took me a long time to get comfortable with it myself. I love my family, I love my brother, I just think he’s closed-minded. He loves me and would go to battle for me, but he’s not very accepting of our relationship. I respect that he loves me, but I wish he would love us. His kids do, and his wife does. He has never been in our house.

“I think it’s the neighborhood we grew up in—very blue-collar and anti-gay. That’s just how it was. He has just not figured out how to figure this out and he does not want to. He has me in this box where I am his brother. We see each other at family events and he’s still a big soccer fan—he calls me about Man U sometimes—but calls are few and far between.” Bono pauses for an extended period. “It’s a bummer.”

Despite some early setbacks, Bono got into the learning and development sector and has been there for 21 years. And after not wanting to see a soccer ball for a couple years after retirement—“My body was broken and I was tired from 13 years of constant competition”—Bono began playing again.

He had represented Puerto Rico in World Cup qualifiers in the late 1980s and had played some high-level amateur soccer after his indoor years, winning a Gerhard Mengel Over-30 national championship with Philadelphia’s Vereinigung Erzgebirge (VE Club) in the early 2000s. He’s also played in the same South Jersey Men’s Masters Sunday league for over 15 years, driving up from Maryland each week. But it was a situation requiring Al’s prodding that has given Bono nearly a generation of happiness.

“Al kept provoking me because I didn’t really have many gay friends, except his friends,” Bono says. “He had a friend who played in Dallas on a gay soccer team and he told me to just try it. I don’t know how many times I said, ‘No.’ One of his best friends, Stephen, called me a few times and invited me to play in a tournament in Rehoboth, Delaware. I had consistently said no until finally I gave in.”

This is where a little hilarity ensues. “It’s the Fourth of July Weekend and it’s a two-day tournament. Philadelphia was taking a team down. I finally said yes just to make Stephen happy and get Al off my back.” After the first game, Bono called Al: “It was just fun to be around gay guys, so I called Al and told him I was going to stay for the second game.” After the second game, Bono called again: “I told him I was playing one more and then coming home.”

After the third and final game of the day: “I called and told Al I was going to spend the night and finish up the tournament. There is a hotel on whatever route and I can get a room.”

And, finally, after the first game on the second day of the tournament: “I called him and asked him if he wanted to go to London.”

After four games in less than two days, Bono was invited to compete in the Gay World Championships in London. By the time he got home, Al already had several flight options available.

“I just loved playing with the guys and hearing how their lives were. Some of the guys I met that first year are my closest friends now. Stephen was in our wedding and he and his partner are just incredible. They were my lifeline because they were out and they knew the lay of the land. I was like, ‘Show me.’ They showed me what bars to go to and told me about great events like Gay Pride. It was things like that.”

This was the summer of 2001, so Bono’s harrowing personal tale of coming out soon followed, but by the following year, Bono was competing at his first Gay Games, in Sydney, Australia, with Al again by his side.

“When I walked into the stadium in Sydney…that was the best thing that ever happened to me. I actually felt like I belonged. I was in tears. It was amazing. All these gay athletes and straight and everybody’s cheering. We won the gold and went from Sydney to Tokyo to L.A. to New York to DC. It was a very long trip, but it was worth it.”

—

Brian Burden covered sports for the Annapolis Capital Newspaper for twenty years. He’s the author of The Sports Tourists’ Guide to the English Premier League and Beer, Brats and Grasshoppers: The Sports Tourists Rank Baseball’s Cathedrals. His writing has also appeared in The Baltimore Sun; The Daily Times of Salisbury, Maryland; and Protagonist Soccer.

Illustration by Devin Dulany, an illustrator and filmmaker born, bred, and based in NYC. Follow on Instagram @devindulany and visit at www.devindulany.com.

Contributors

Brian Burden