Soccer’s a lot of things. But even when it looks like just another day in the park, it’s never just another day in the park.

Tío Lobo says that anyone in the business of running fast should avoid cutting their toe nails. Cutting keratin, the protective protein that extends from one’s feet reduces, Lobo theorizes, the amount of friction between the futbolero and the pitch. He has told us, the cousins, this over and over again. Every time though, he acts like it’s this new thing he just uncovered. He leans in and in a hushed tone asks us if we know the secret to running fast. “Si, Lobo,” we answer in unison as we chuckle.

We think Lobo is full of shit, but we’re not too confident about it. For years we knew this toenail thing made no sense, but then one of us saw that kid show “Wild Kratts” while we were babysitting and found out that the fastest land animal in the world is the cheetah. Why the cheetah? Its entire body is designed to defy gravity. It’s got a flexible spine, super big heart, huge lungs, and retractable-mother-fucken-claws. The claws dig into the ground and help the cheetah propel forward.They only come out when the cheetah needs to catch some prey. The point isn’t that soccer players are like cheetahs or that soccer players should run around barefoot, but that Lobo was kinda right. This is typical Lobo. His ideas are always in that space between genius and, well let’s just say not genius.

Our grandparents didn’t name their first son after an animal. They named him Manuel and somewhere along the way someone thought he should be called Lobo. Maybe they were right because it stuck. Unlike his siblings, Lobo never married and is not into having a regular 9am-to- 5pm Monday-through-Friday job. He puts together a part-time job with some sort of quasi-legal side hustle. For a few years, he spent most of his nights delivering pizzas at Rusty’s Pizza Parlor and teaching undocumented paisas to drive during the day. But now he is the sole owner of a one-car taxi cab company that he cleverly dubbed Easy Cab. Instead of waiting for someone to call him, though, he drives up to a bus stop and tells whoever is there that for five dollars he will take them wherever they want to go. If folks are running late to work, they’ll spend the extra three dollars to get going and thus expand Easy Cab’s customer base.

We are not sure if this is a good business strategy, but we know two things: Lobo can take a break whenever he wants and Lobo always has a soccer ball, shorts, t-shirt, and cleats in his trunk. The only problem with playing with Lobo is that we, the cousins, are serious soccer players, so we have no time for his theories.

Take today. It’s the first day of summer, which means that we don’t have school and that the soccer season is just a few months away. Jean Carlo and Ismael, the forward and goalie, are getting ready for their second season at Santa Barbara City College and Dante and Fernando got their first year of high school varsity to train for. I’m not training for anything, but I view everyone’s development as a family affair. Some families pass down recipes, we transmit skills and a passion for fútbol.

As we get out of the car and head out to the field, I contemplate inviting Lobo. I’m torn not because I want him to train with us, but because I want to bet and beat him at penalty kicks. I want my money back.

See what happened was this: last Saturday, like most Saturdays, I hit up the clubs on State Street with the homies. At the end of night, I am driving down Milpas Street to drop off Jorge and the others. We get near Rusty’s Pizza Parlor and out of my right eye I see Lobo’s Easy Cab and tío Lobo jumping up onto the bumper of his car. I blurt out “what the fuck?” and the homies and I start laughing. It occurs to me that he might be locked out of his car so I turn into the parking lot and park next to him. He doesn’t stop though. I get out and I’m like, “Lobo, what are you doing?!”

“Sobrino. Me faltan cinco. Esperame.” He finishes his five jumps and then tells us that he is waiting to pick up a customer who gets out at 3 a.m. and that every time he arrives early to pick someone up he does these jumps and juggles the ball. To demonstrate how brilliant this is, he asks me to do ten. “Solo diez,” he says. I’m in my fancy clothes and it’s been a long night of drinking, dancing, and more drinking so I want to say, “Nah tío, I’m good,” but I realize it’s probably the fastest way to get home. I begin and quickly realize how hard it is. My shoes have no friction and the bumpers of cars, as you know, aren’t made for folks to land on. In a regular “jump box” exercise you jump firmly onto a box, gain your balance, and then jump back down. Because you can’t stand on the bumper, your legs don’t get to land and rest. I hit ten then collapse onto my thighs and try to catch my breath. Lobo pats me on the back and smiles as if he’s about to show me some secret cheat sheet code on PlayStation.

“Mijo, this exercise is amazing. Because of them I can juggle the ball more times that anyone I know.” I make the mistake of saying, “Pues quien sabe tío.” He smiles and sets the trap: “Yo tengo un par de minutos si alguien quiere ganar un par de dolares.” Jorge doesn’t see what is happening. All he sees is a sixty-year-old man wearing an old, wrinkled button-down shirt and unfashionable dress pants. “I got ten dollars,” he boasts. Before I can intervene, Lobo pops open his trunk and takes out a soccer ball and black Adidas shorts. As his pale legs slip out of his pants and into his shorts, he tells us that pants are longer than shorts and thus weigh more. Pants require, he explains, more energy and over time will greatly limit one’s endurance.

Lobo goes first. He casually and calmly juggles the ball with his left and right foot, keeping it just below his knees. He gets to 10, then 20, then 30, then 40. As he reaches 60 he stops counting and softly kicks the ball to Jorge. “I’m tired. I think these shorts are too long,” he tells us in his best English. We’re laughing at Lobo and at Jorge. Dude is in that space between tipsy and drunk and is wearing slacks, a lame-ass red vest that makes him look like the dudes who park cars, and some new Kenneth Cole dress shoes that he has been bragging about all night. He starts juggling and we start clowning, “If you take your pants off, your legs will be lighter.” “For real fool, you prolly should have warmed up with the bumper of the car.” Jorge can’t focus and loses control of the ball at around 20. He digs into the abyss of his pockets and pulls out tiny balls of lint. “Spot me ten man, I’m good for it.” If someone has to tell you they are good for it, this is a pretty good sign that they won’t pay you back. I hand him ten dollars, which he then hands to Lobo.

Losing a bet is real shitty, but even worse if you didn’t make the bet and didn’t get to compete. So, you see, I want my money back. I know the cousins won’t be up for playing with Lobo so I tell them that I’m going to call Lobo and tell him to join us in 90 minutes, after we’ve trained.

We put on our cleats and start doing a series of warm-ups: we jog a few yards, stretch a muscle. Jog some more, stretch again. Then, in unison we do that Mexican warm up thing that is somewhere between a march and a dance move. We move forward a few steps, lift our right leg up, then out in a circular motion away from our body and then to the ground. As soon it lands, we repeat, but with our left foot. Then do it again for about 50 yards.

Being the oldest of the group, I need extra time to stretch. From the floor, I throw my left leg across my body, with my upper torso facing the opposite direction. I spot a posse of paisas arriving on their BMX, mountain, and old road bikes. After spending much of our childhood, adolescence, and adult life on or near fields and around Mexicans, we’ve adopted a visual vocabulary and the ability to spot paisas and evaluate soccer players. Paisa is a term that only really exist in cities and states with Mexican migrants. It denotes a set of aesthetics and cultural affinities, but more generally the length of one’s stay. Paisas work in the kitchens of restaurants, mowing lawns, and, in some cases, drive a taxi.

As they take their jeans and shirts off, I wonder where they work and if they might have all been friends or even cousins in Mexico, maybe even from Guadalajara. I imagine that they lived together, cook for each other and drink a few beers after work. In the late 1960s, our own grandfather, a long-time migrant, lived and worked with distant relatives and other migrants around Pueblo and State Street, the historic Mexican barrio of Santa Barbara. In the early 1980s, all our fathers made their way north, arriving with friends and relatives, before establishing their own homes.

Instead of Dri-FIT jerseys of their favorite European club team or 200- dollar Nike Vapor cleats, the paisas are wearing old t-shirts and generic plastic cleats from Big 5

They don’t jog or stretch or even pass the ball. They walk to the eighteen-yard box and start taking shots on the goalie. Despite his best effort, the paisa in the goal cannot touch the crossbar and this defines the challenge before the shooter: “chipping” the ball just above the outstretched arms of their comrade and just below the bar. The shooters are so giddy at this sight that they laughed right before kicking the ball, sending it a pair of yards above the goal, provoking more laughter and more jokes.

I get up, off the floor and return to the boys. The cousins and I engage in one- and two-touch passes and alternate between sprinting and jogging. The forward hits the ball and sprints towards me.

“So primo, what are we gonna work on today?” he asks.

“Not sure, I was thinking we’d start with some one- and two-touch exercises, follow it up with some short sprints, shots on goal, one-versus-one, then two-versus-two with your bro in the goal. When Lobo arrives we can cool down with some penalty kicks. Cool?”

“Sounds good. Let’s bust some crosses after shots on goal though.”

“Sále,” I affirm.

I look over at the paisas. I want to see if someone has scored or if they have changed goalies. I was surprised to find the goalie—now, in his new position as ambassador—jogging towards us. He should have looked taller as he approached, but he didn’t. He looked just as short as he did when he tried to touch the top of the crossbar.

“Quieren jugar?”

“Creo que no. Pa’ la otra,” I reply.

“Bueno, OK.” The goalie turns and trots back to his friends.

The boys approach. We’ve all played fut’ long enough to know that when a member from one group runs over to another it is for one reason and one reason only—to get a cascara on. Like an offering of food, it’s generally rude to decline.

“We gonna play them or what?” asks Dante excitedly.

J.C. shakes his head, “You’re fucking with us right? You really wanna ball it up with paisas? Fool, we need to work.”

Amidst the discord, Lobo arrives and is greeted with J.C. turning to me and whispering “Ah, shit. We might as well play now. Don Quixote arrived mad early.”

It occurs to me that we could send Lobo over to play with the paisas, but that would be fucked up, so I tell Dante to tell the paisas we’re game. He jogs a few yards before deciding to simultaneously deploy the Mexican whistle and the fail-safe motion of the hands. They gather their bags and ball and ride over. They can’t decide if it’s faster to ride on the grass or merely to walk their bikes. They alternate between both, laughing and joking in between.

They park their bikes behind the goal, just as they did on the opposite side of the field. We all walk over, shake hands and murmur our names. In his pretty good pocho Spanish, J.C. suggests that we divide up the groups, but the paisas confidently decline. Not wanting to offend them by asking again, I use the eighteen-yard box to demarcate the field and place bags as goals on the short sides of the perimeter. I’m content knowing that a small field will force us to release the ball quickly and dribble in tight spaces. We might salvage the workout.

When you’ve played together for years the formation emerges organically. Dante goes up top, J.C. and I take the midfield, Ismael and Ferni play defense and Lobo positions himself as the last man.

As is customary in all cascaras the ball is kicked high in the air. Only upon its third bounce are players allowed to touch it.

Dante gathers the ball near their side of the field. With only two players to beat and sensing some disorganization, he attacks the first player and J.C. makes an overlapping run. Dante gets through the first player easily enough, but as soon as he does, two players close ranks—the original defender, plus another—and don’t give him enough time to release the ball or take a shot.

With Dante and J.C. out of the equation, one of the paisas pushes forward and quickly, toward me. I step up, committing to both the ball and player. Using a quick give-and-go, he gets around me as well, putting his team in an advantageous 4-versus-3. Ferni and Ismael quickly mark up the players closest to the goal—a smart move indeed, as they were, technically the most dangerous players—leaving one player unaccounted for and Lobo before a 1-versus-1. The paisa fakes like he’s going to pass the ball to the open player on the left side of the field and pivots to his right—Lobo takes the bait and stretches out his foot to intercept the pass. With the outside of his right foot, the paisa pushes the ball to the side, creating enough room to take a goal-scoring shot. With just one possession and less than a minute into the match the paisas are on the scoreboard.

The rest of the game is some version of this first set of exchanges. We beat one or two of their players and occasionally connect a few passes. For the most part, we are out of sync. The paisas smartly double-team us when we hold the ball too long or anticipate our passes when we actually release it on time. We are unable to figure out how to crack their defense and do not know how to adjust. When we do score it is a result of individual effort and talent. For every goal we put in, they put in three. A losing ratio.

At the forty-minute mark and after sliding in another goal, the paisas offer, “Ultimo gol gana?” Wanting to put this behind us, we gladly agree. Though we all know that team paisa is way up on the scoreboard, this is their gift to us: “El gol de honor,” our chance at redemption. If we score, at least from our point of view, it would prove that we had a bad day and the paisa slaughter of the pochos was a mere fluke.

I look at Dante, raise my eyebrow, signaling for him to stay up top. With my left hand I motion to J.C. to take possession of the ball and for Ismael to drop back. Together, the three of us will move the ball forward.

J.C. attacks their nearest player and gets around him efficiently and quickly. He then passes the ball to me, in the middle of the field. Instead of returning the pass, as the paisas and everyone thought I might, I take it in the opposite direction and find Lobo on the left side of the field. With one touch he puts the ball between the paisas legs and sprints towards the goal. He musters all his energy to his right leg, convincing himself that he is going to take a shot. The paisa flinches, and Lobo uses the outside of his foot to get it to Fernando. With a simple and quick one touch, he slips the ball to Dante. Five yards in front of the goal, he hits a rocket.

The paisa slides and lifts his left foot just high enough to stop the shot. The ball deflects like a pop-fly towards Lobo. Lobo jumps, but his feet betray him and the ball sails an inch over his head. It bounces once and before it can bounce a second time, the paisa hits a twenty-yard pass to his running teammate, who finds himself with no one between him and the goal. Instead of letting it bounce and running the ball into the goal, he turns towards us, hits the ball up with his chest, and flicks it into the goal.

This was by far their most skillful, and thus annoying, display of teamwork. As Lobo dutifully chases the ball, he turns back and yells “Buen gol.” Our frustration with each other and with our defeat is palpable, almost audible. We can’t decide what is worse: how bad the paisas balled us up or Lobo’s play and consequent celebration. I mean, how the fuck is it possible that he can jump high enough to touch the bumper of his car at 3 a.m. on a Saturday but can’t time a simple header?

The paisas, with their ersatz jerseys, yard-sale-bought bicycles, and cheap rubber cleats had mastered the two basic principles of soccer: time and space. When one of their players lost the ball, they all hustled back to play defense, every one of them making sure to help with the effort. When they had the ball, they provided each other with passing options—at least two—and quickly released the ball, ensuring that all of them were given time and space to do something with it. Their effort on the pitch mirrored their daily life and everyday struggles. Our fathers, at one point, were migrants, and, paisas too. They’d played soccer, and done their fair share of balling on Santa Barbara’s soccer fields. We inherited their skills, but on this occasion at least, we forgot to incorporate the paisa hustle.

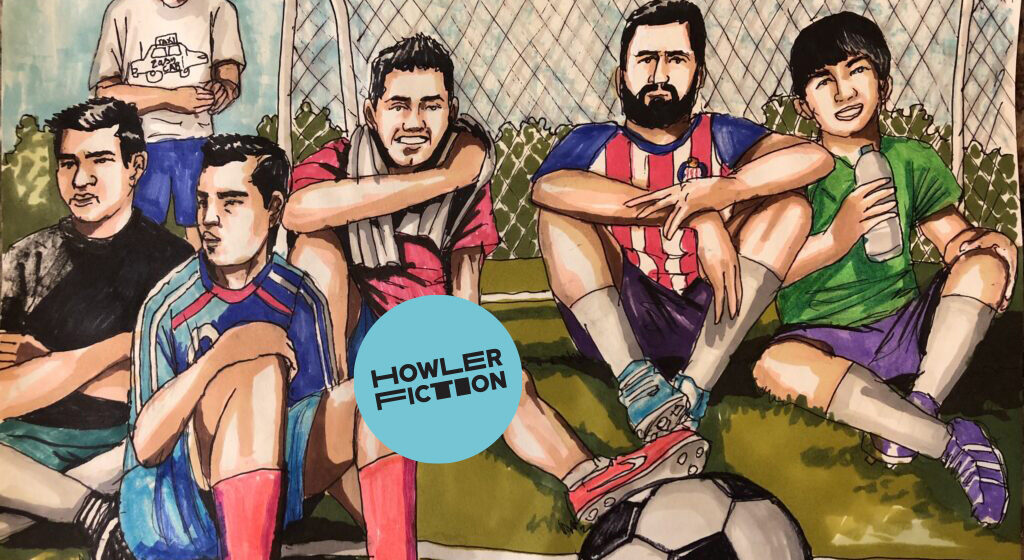

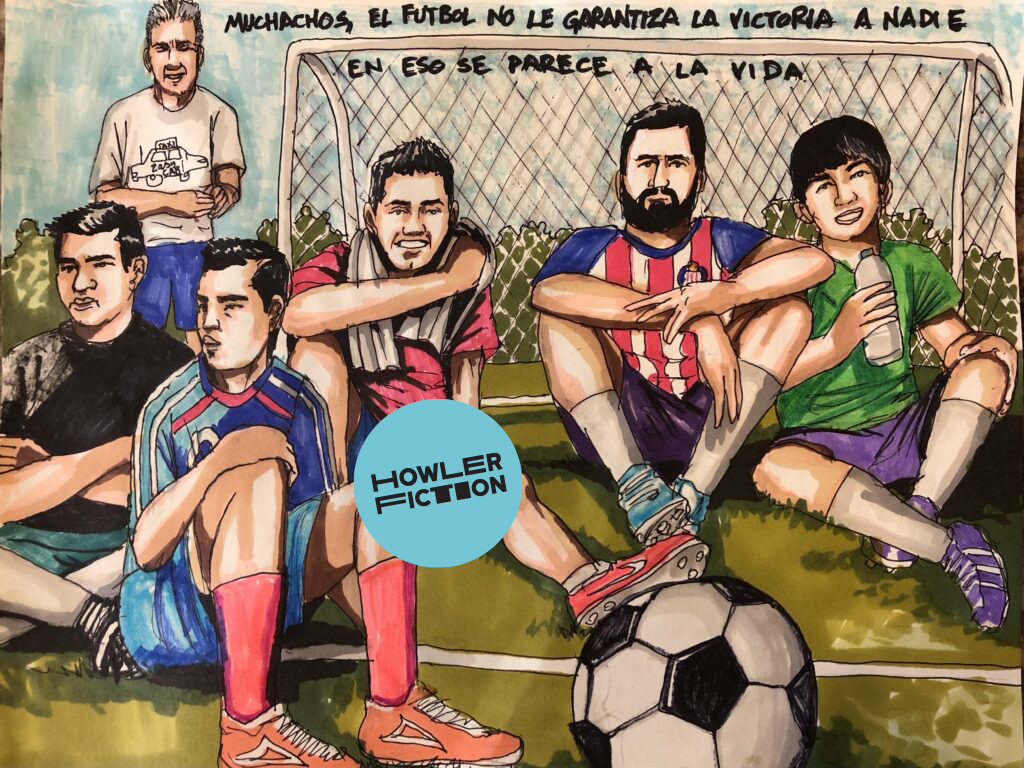

We free our feet from our cleats as if they took part in our poor performance. Lobo sits with us, but he doesn’t have time to indulge our emotions. He slips into his dress pants, gets up, and speaks in his classic Lobo way: “Muchachos, el fútbol no le garantiza la victoria a nadie. En eso se parece a la vida.” (“Soccer, like life, doesn’t guarantee anyone a victory.”) By the time Lobo gets into his Easy Cab, the cousins have agreed that we were not at our best, but that the old man was the last man and thus bears the most responsibility for the loss. I want to agree, but can’t help feeling like we’ve lost something along the way.

Contributors

Romeo Guzman

Romeo Guzmán is a history professor in the San Gabriel Valley in California. His academic work and public history projects often focus on Mexican migrants and Mexican-Americans. This includes an essay on the transnational history of Mexican futbol players as well the public history project “The Other Football: Tracing the Game’s Roots and Routes in the Central Valley.” He is also the co-editor of East of East: The Making of Greater El Monte (Rutgers 2020) and Writing The Golden State: The New Literary Terrain of California (Angel City Press, 2023). On Sundays he is reminded of his age. For more on his work visit romeoguzman.com

Fernando Corona

Fernando Corona is a visual artist with roots in Mexicali Baja California Mexico. He studied Fine Arts at Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes in Mexico and the Pratt Fine Arts Center in Seattle. A member of the Mexicali Rose art community in Pueblo Novo, his work goes from muralism, painting , installation, sculpture, stop-motion and illustration. He is a longtime contributor to Boom California and his work can be found on instagram.