What the 35-yard Shootout Meant to American Soccer

January 14, 2022

WORDS

Billy Merck

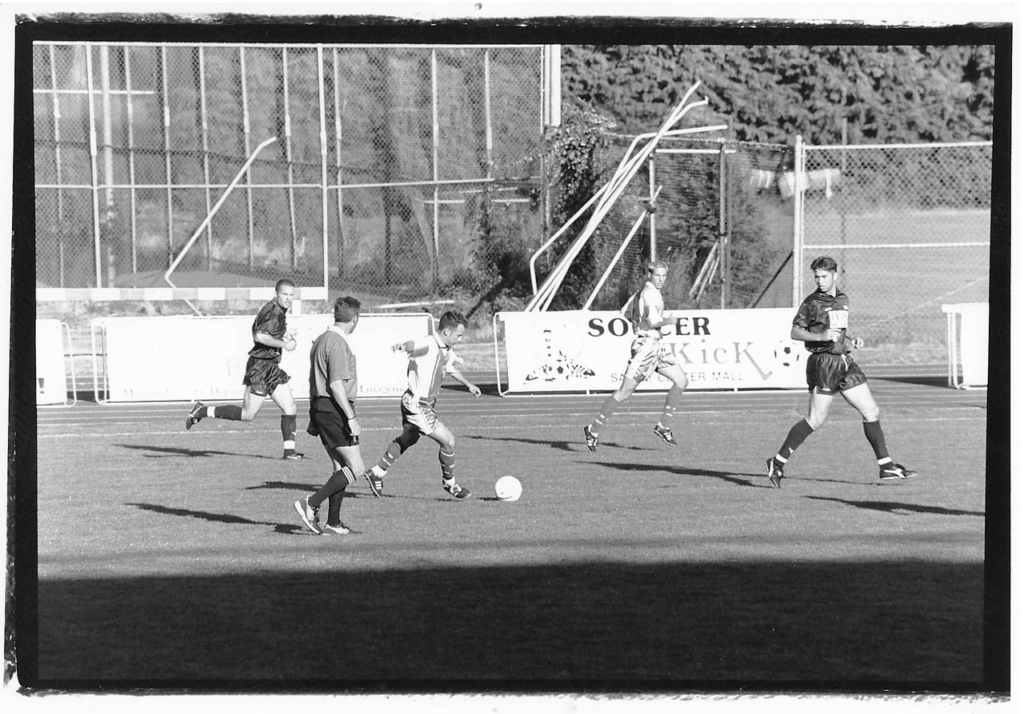

The author as a member of the Portland Pythons (World Indoor Soccer League, 1998-99)

There’s a video I can’t get enough of. It’s from a 1980 North American Soccer League 35-yard shootout between the New York Cosmos and Washington Diplomats.

There are just north of 53,000 fans in RFK Stadium, and they are into it. In the video, Dips goalkeeper Bill Irwin—tall and mustached, with a massive mane of curly hair—turns away four consecutive Cosmos shooters, literally bare-handed, until the fifth shooter, Vladislav Bogićević, beats him with a left-footed shot. That’s all the Cosmos need to secure the points, as no Dips player scores. Irwin, sans gloves, looks, as do many of the NASL players from ’70s, like he could wrestle a bear and then buy the bear a beer. No hard feelings. They were just doing what they do, Bill and the bear. At one point Bill becomes irate over a Cosmos coach encroaching behind the goal. Irwin’s successful challenge on third Cosmos shooter Andranik Eskandarian sends the 5’9” defender to the ground. The 6’3” Irwin helps him up, tucks him under his chin, gives him a quick rub of the head, and both are off. There are more shooters, more 5-second duels until they get a winner.

The video hits the viewer right in the nostalgia, and a fan of sport, especially soccer—and especially American soccer—has so much to enjoy in that end-of-game shootout. ABC’s Jim McKay, Paul Gardner, and Verne Lundquist, the grainy-ish video, the accidental upside-down clock. Viewing it is to be both participant and voyeur in the best Wide-World-of-Sports sort of way. The sort that isolates one dramatic, definitive moment. It is timeless.

The quirky, sometimes-beloved, other-times-maligned shootouts are an unmistakable twice-employed American alteration to the Laws of the Game, first in the NASL, starting with the 1977 season, and then in Major League Soccer (and occasionally in lower leagues), from 1996 to ’99. Beyond determining a winner, the five-second runners were exciting for fans and gave goalkeepers more of a chance to decide their own fate. This now-dormant American contribution bookends a series of eras that gave us what we have today, maybe at the sacrifice of “traditional football,” maybe at risk of being seen as a gimmick, but always in an earnest attempt to first and foremost build the game in this country, something that both enables and transcends the entitlement of the contemporary fan.

Like end-of-season playoffs, the 35-yard shootouts are an intentional American nuance in the form of adaptation for survival and a reminder that there was a time when the American soccer ethos conjured its inner Clint Dempsey. It was unapologetic, it “tried shit.”

I wasn’t yet born when Clive Toye and Phil Woosnam bought the U.S. television broadcast rights to the 1970 World Cup for $15,000, when Toye called the games from Mexico while looking at a television set in a hut made from egg cartons. But I was nearing my playing prime a short 26 years later, when Major League Soccer started. Because of the NASL’s early efforts, there was a foundational template for professional soccer in America, albeit a tenuous one. Leagues have come and gone, but the spirit endures: build the league; build the game, by any means necessary. Now, when I take my seven-year-old son to a Portland Timbers game, I think about the conversations I had to write this essay, and I think about the shootouts that stadium saw forty years prior, and it’s not lost on me that he is, in a way, a third generation of American soccer player, and there’s something there for him, as there was for me. I’m thankful for those who made the game here.

The 35-yard shootout was only one of many things our forebears tried—and there is quite a list, from NASL to MLS, where every person involved just wanted the game to survive and thrive in the U.S., regardless of the means to accomplish it.

Moments, singularly and collectively, like the shootouts, tell the story. Irwin, who was born in Northern Ireland, put the NASL shootouts in this perspective: “There was some talent in the old NASL,” he said. “You had world class players coming at you, one on one, and you’re going ‘shit,’ and you do your little bit against them…”

In that 1980 Cosmos/Dips shootout, that “little bit” happened to be, in four consecutive one-v-one situations, turning away World Cup-winning captain Carlos Alberto of Brazil, Paraguayan legend Julio César Romero, Iranian Asian Cup winner Andranik Eskandarian, and Croatian-born U.S. international Mirko Liverić.

What can you accomplish in five seconds? Could you, with certainty, start 35 yards from goal and score in that time? What about after putting your body through 105 minutes of soccer, possibly on thin AstroTurf laid on top of concrete? How about with a 6’3”, bare-handed Northern Irishman coming straight at you? With your team’s points on the line? In front of 53,000 people?

:05// “Strange at first…”

Peter Ward, 1982 NASL MVP, Seattle Sounders

Major League Soccer’s first game ended about as perfectly as it could have. U.S. National Team player Eric Wynalda scored the league’s first goal in the 87th minute. He pulled his shirt over his head and slid toward the sideline, celebrating with his San Jose Clash teammates. The television camera panned to a shot of the scoreboard, a still-running clock counting down the last three minutes of the match. Gary Glitter’s “Rock and Roll” played in San Jose State’s Spartan Stadium.

Wynalda scored so close to the end of the game that the emotion of that moment remained as fans left. It’s special, poignant. More so than, say, a ninth-minute own goal. Or a hard-fought 2-1 win, with all three goals coming in the first half. Producing a result so close to the end is the height of drama. What a way to launch a league.

Imagine, however, under current MLS rules, Wynalda not scoring as the last minutes of what was a sloppy, disjointed soccer game tick off, the final score ending 0-0. Both teams get a point in the standings. Of course, now, that makes perfect sense. It’s football. But in 1996, trying to launch soccer, again, in a country that perpetually eschewed the sport…an 87th minute winner is, no doubt, miles better. “Thank god for Eric Wynalda,” then-MLS Deputy Commissioner Sunil Gulati later told Sports Illustrated writers Grant Wahl and Brian Straus.

But had Wynalda not scored, MLS had a Plan B: 35-yard shootouts.

“You’ve come to the right place,” Wynalda said when I asked about the shootouts. “I hated that thing.” The National Soccer Hall of Famer took me back to that day in 1996. “When we started the league—the clock counting down…I can tell you this, without a doubt, one of my number one motivations in the first inaugural game was do not let this fucking game go to a shootout. That was my mindset. And it wasn’t about scoring the game-winning goal. I wanted to score, but I just did not want to do that shootout. I thought it would have been the worst message to the American people.”

“As a player,” Wynalda added, “after you’ve already played an entire game, and then to…I just felt, as a purist, let’s just take the point and then go find the locker room.” Wynalda’s response is not unique to the MLS versions.

Ron Futcher, fourth all-time NASL leading goalscorer, made a living finishing during the run of play. To score 119 goals, Futcher said, you just have to “stick your head where no man should ever stick his head.” But for the shootouts, Futcher was less aesthetic: “I particularly didn’t like them.”

“Strange at first.” That’s what English international Peter Ward said about the shootouts. “Strange at first but just like going on a breakaway with no defenders against you, just the goalie. There’s no pressure behind you.”

NASL Timbers legend John Bain ranks tenth all-time in NASL assists and 18th in total overall points. The Scottish midfielder said the shootouts were “really exciting because you couldn’t have ties, so basically it was the difference between winning and losing,” and “even though it wasn’t ‘soccer’ so to speak, it was better for the fans.” Ward’s and Bain’s pragmatic responses echo the sprit and professionalism of many involved in not just the NASL but also MLS iterations of the shootouts.

Current Toronto FC head coach Greg Vanney sides with Wynalda and Futcher. “As far as outcomes,” Vanney says, “I didn’t care for it.”

Like them or not, one thing the shootouts did was manufacture a moment. They moved the emotional impact of a match as close to the end of the game as possible, and, when building a fan base, emotion preceding intellect isn’t necessarily bad, especially when those moments endure.

In the 1996 MLS Western Conference Finals, then-rookie Greg Vanney recalled, “they called a PK against me that ended up being the goal that put us down 1-0,” referring to a 69th minute foul that led to a Preki penalty, giving Preki’s Kansas City Wiz a potential series-evening win over Vanney’s Galaxy. But Vanney was twice redeemed, scoring a 77th minute free kick to send the game to the eventual shootout, where his successful attempt against now-Sounders GM Garth Lagerway decided the game and the Western Conference finals. “I thought I was going to be the goat there for a minute,” Vanney told a reporter after the game.

Vanney’s contemporary, current Sporting Kansas City head coach Peter Vermes, was also the center of a memorable shootout moment from the 1996 MLS playoffs. On September 24 of that year, Vermes, the U.S. international and 2013 National Soccer Hall of Fame inductee, was suffering from an injury and was pushed back in the shootout order, to the 11th spot, in hopes it would be settled before he’d have to shoot. Vermes’s complete absence wasn’t to be. The shootout was tied after 11 DC United shooters and 10 from Vermes’s MetroStars.

Before Vermes started, he turned to referee Esse Baharmast and said, “Esse, if I shoot, we win.”

Such audacity for a player having a hard time walking, after a full match, plus, on the Giants Stadium turf and with a torn muscle. Vermes took two touches and then slightly chipped the ball over DC United goalkeeper Jeff Causey. Vermes knew Causey was aggressive and “wanted to knick the ball over, play more on his aggressiveness than anything.” The ball went in, Vermes hopped off, and the MetroStars claimed Game 1 of the Eastern Conference Semifinals.

Truth be told, Vermes meant to confirm, “If I score, it’s over,” in a manner more of a question, trying to calibrate what his team needed in the moment. But what he said was picked up by ESPN microphones and, paired with the chipped finish and hobbling skips off the field, was a better drama, something the fans could immediately take home with them.

NASL legend and former U.S. National Team goalkeeper Winston DuBose had his own shootout moment with the Tampa Bay Rowdies. DuBose told me he felt terrible when, in front of over 54,000 home fans, he dropped the ball with under a minute left, and Georgio Chinaglia pounced to tie the game at 3. That happened on June 14, 1980. Up 3-2 at home, all signs had pointed to a Rowdies’ win and a move into first place in the American Conference Eastern Division until Chinaglia capitalized on the DuBose mistake with the clock reading 89:13.

But then DuBose found redemption in the shootout, stopping all five Cosmos—Carlos Alberto, Angelo DiBernardo, Seninho, Franz Beckenbauer, and Vladislav Bogićević. “I had to do what I did to make up,” said DuBose in Tom McEwen’s The Tampa Tribune Sun article. And what DuBose “had to do” was win his one-v-one battles with some of the best players in the world, an Irwinian feat that took him from 90th minute goat to shootout hero.

Maybe the shootouts trend goalkeeper too much, and contemporary soccer fans wouldn’t want to see, say, Messi, Suárez, Rakitić, Dembélé, and Griezmann possibly fail in order—or get injured—when conventional laws say share the points after 90 minutes. That’s understandable. Marketing, traditions, and ubiquitous cups/competitions provide enough drama, subplots, and soccer that there’s not as much of a need for closure in every single match. Building a league means to be cognizant of, if not beholden to, global standards and leanings, and any proper league is smart to see that. Peter Vermes grew up watching the NASL and viewed the shootouts as an “American take on how to bring more excitement to the game.” Ultimately, however, Vermes said, fans “didn’t want a gimmick; they wanted what the rest of the world wanted, which was a game.”

:04 // “My style was to try and score”

Tony Meola, National Soccer Hall of Fame Goalkeeper

Eric Wynalda could have scored the first 35-yard shootout goal in MLS history as well, when, on April 14, 1996, his San Jose Clash went to a shootout with the Dallas Burn. Burn goalkeeper Mark Dodd, however, got enough of a touch on his attempt, leaving Dallas substitute John Kerr to convert the first, just moments after finding out he was even going to take one of the shots.

Similarly, the Seattle Sounders’ Harry Redknapp missed wide left at the first NASL in-season shootout on April 8, 1977, opening the door for Team Hawaii’s Brian Tinnion, who slotted the first for his league. The shootout lived 8,248 days, until it was last seen in the wild on November 7, 1999 when another Burn player, Ariel Graziani, converted to force a Game 3 of the 1999 MLS Western Conference Finals.

From Tinnion to Graziani, and moments like a traditional kick from the mark within the shootout—Dallas Tornado’s John O’Hare had the first of these on April 24, 1977—or Franz Beckenbauer’s 1978 Eastern Conference Semifinal-ending finish that sent 60,000 fans into a frenzy in the Meadowlands, the 35-yard shootout ensured no match would end without a result.

When it was introduced to replace penalties for the 1977 NASL season, Commissioner Phil Woosnam said it “duplicates the condition of the game.” Traditional kicks from the mark are around 80% successful, but the NASL found the 35-yard moving versions to be closer to 40%.

At a 40% success rate and a moment when points are on the line, Greg Vanney suggests shooters, “have a plan, be consistent, know what [they’re] going to do because in these bigger moments [they] don’t want to be making stuff up.”

When I played in the USISL, my plan was to get the ball to my left foot at the most important time—something I could, within reason, replicate in any stadium I’d find in the Pacific Northwest, on flat or crowned fields, short AstroTurf or long grass, with the (American) football lines painted or burned as crevasses into the grass: One long touch to get the keeper coming and clear a dozen yards of unpredictable field anomalies, one short touch to get the ball to my left foot, one long shot that just had to pass the then-current position of the keeper more than anything. It wasn’t the headiest of plans, but it was a plan. As a defender, I didn’t often consider being on a breakaway.

But I had a style—get the ball out from under me, so I could have a think. Those first 12 yards had more dangers than anything; I decided to just skip them with a long touch, so I could look at goal. It’s the same strategy I’ve passed along to my son to help him get out of the pack in his bunch-ball league, so he’d find a way to get space and be able to look toward goal before taking a shot. It simplifies the process, especially when the obstacles are fewer than in a game. For him, it yielded a first hat trick, but for me, it allowed me to size up the goalkeeper as time was ticking down.

In MLS, one unique style belonged to Jeff Agoos. When I interviewed the MLS Vice President of Competition, I prefaced a question with, “As a defender, I took a few of these in the USISL,” and the US international and 2009 National Soccer Hall of Fame inductee was quick to joke, “I’ll take offense that ‘defenders don’t have skill.’” He then continued to talk about the difficulty of the shootout, as “much harder than a penalty kick because a penalty kick is more of a binary type of decision,” and then went on to discuss the more even, skillful nature of “running penalties” as ways to satisfy ties.

From the shooter’s perspective, Agoos described his style (putting the ball into the air) as this: “I definitely took it from the old NASL [from watching Carlos Alberto]. I remember going to see games and seeing that being done, and saw how skillful that was. When I first took the shootouts, I didn’t start that way. I started off on the ground. I just felt like by starting on the ground I give the advantage to the goalkeeper because there’s just one opportunity, which is to place the ball or beat the goalkeeper.”

And when I mentioned Carlos Alberto’s style to Wynalda, I found out why Agoos may have been so quick to stand up for defenders, himself included. “Jeff Agoos used to do that, and I was like, you know that takes balls,” Wynalda said. “I’m going to keep the ball on the ground. I don’t want it bouncing around.” And as soon as Agoos missed one, Wynalda said, “We all gave him so much shit for that. We were like, ‘yeah, left back doing the super talent move. Good job, buddy.’” So though I know why Agoos might have been quick to stand up for us skilled left backs, the time bought by putting the ball in the air makes the risk worth the reward.

Agoos’s explanation of his style illuminates how it’s possible to then make split-second decisions in the moment. “If I lift the ball,” Agoos said, “I’ve now made the goalkeeper make an instant decision as to what his next choice is, and, based on what his choice is, would then predicate what my next decision was going to be. It was sort of a decision tree.”

“If I lifted the ball, and I knew the goalkeeper is coming out, I’d continue to lift the ball again and have an opportunity to chip the goalkeeper. If the goalkeeper stayed on his line, I would then be able to put the ball on the ground and have a wider goal to shoot at. What I tried to do was leverage the decision so I would have the best possible opportunity to score a goal.”

All of this took place, keep in mind, in five seconds. But to Agoos, it was the best process because “it forces the goalkeeper to make a choice, which would then make it easier for me to determine which direction I was going to go.”

Consider the time and space that makes up the moment. At five seconds and 35 yards, time and space start to collapse immediately at the whistle. Most goalkeepers use the first second and a half to close a few yards—but not too much—and read the shooter. Most shooters take a longer-than-normal touch to prepare to shoot and to read the goalkeeper. That leaves about 3 and a half seconds and maybe 10 or 12 yards of space between the two players. Another touch or two from the shooter, the goalkeeper trying to get in position and get his feet right. Now, there’s maybe a second and a half to two seconds for the balance of this moment.

:03 // “A left-footed shot…Paul Caligiuri has scored a goal, and the USA lead one-nothing”

JP Dellacamera

In 1991, the Chicago Bulls won their first NBA championship, Nirvana released Nevermind, and, in Portland, Oregon, I was a bemulleted high school junior, trying to get the tongues of my Copas as long as possible while still being able to walk. In addition to style, I was also oblivious to the major shift happening in American soccer. This time, between 1989 and 1991, was not only the midpoint between the NASL and MLS shootouts but also the generational transition period where the vision of the NASL originators was about to be realized, just without the NASL.

A 1991 American professional team might have both NASL and MLS generational talents, like U.S. international goalkeepers Arnie Mauser and Tony Meola, as the American Professional Soccer League’s Fort Lauderdale Strikers did. Or Peters Vermes and Ward, as did the same league’s Tampa Bay Rowdies. The ’91 APSL champion San Francisco Bay Blackhawks featured Marcelo Balboa and Eric Wynalda, both of whom would play on the ’94 U.S. team. Of the people already mentioned in this essay, many of the NASL veterans were retiring, like Winston DuBose, who called it a career in ’91, and others were just getting started. Jeff Agoos logged games with both the APSL Maryland Bays and the indoor Dallas Sidekicks. Greg Vanney, like me, was still in high school.

The U.S.National Team was also transitioning, from coaches Bob Gansler to Bora Milutinović, through a time that saw the U.S. lose to Bermuda in February but win the Gold Cup in July. Inside that transition is a three-game chasm helmed by interim head coach John Kowalski, the recent Robert Morris University women’s coach. Kowalski managed the 1991 U.S. team to a draw with Mexico and to wins over Canada and Honduras.

Though Bora gets credit for the Gold Cup win, Kowalski had a heavy load to lift because Bora wasn’t as familiar with the player pool. Kowalski knew many of the younger players and took a U.S. “B” team to a Corona Cup in Vancouver, British Columbia in ’89. In a time between stable domestic leagues, caretaker Kowalski was more than turnkey middleman; he was an essential recruiter because he could navigate the spaces where players were; Kowalski was connected with US Futsal, the indoor leagues, and the college game.

Also of note during this time was a transition in style of play. Kowalski helped shepherd the U.S. to “more of an international way, with more ball possession and knocking the ball around,” he said. The team started to “pass and move [with] players opening up spaces without the ball, in relation to the spaces available, versus a little bit more of [a former] American style of play when you send the ball and you press and play counter attacking and packing it in. We were able to establish a little bit combination of American and international way of playing.”

This time also represents the first significant generational handoff in American soccer culture. There are details in the rosters—Kowalski oversaw Alexi Lalas’s first cap (against Mexico) and paired Lalas with Balboa, and he brought in another college player, Dante Washington—but a wider lens tells another part of the story.

Those kids who watched the NASL were now of age to play professionally. With all due respect to the 1930 team and what they did, this transitional time begat the first consecutive second generation, the end of the 40-year World Cup drought, and it was filled with players who took the torch from the NASL players of the 1970s. For some, they had the benefit of parents from a soccer-loving country. For others, they had the NASL but were still of the generation where children had to explain the game to their parents.

This era is so important to the national landscape of the game because, just a cycle sooner, the U.S. was transitioning away from NASL-focused national teams. U.S. teams in the first four years of the ’80s played as many games as a youth team might in a month now: 8 between 1980 and 1983 (not at all in ‘81 and once each in ‘82 and ‘83). And it wasn’t until 1988 that the team’s one-year total of matches played reached double digits. “It really happened in ’85 and ’86, when we went to World Cup qualifications, the change of the guard started then,” said Winston DuBose, who last played for the national team in ’85. “There were NASL players on that roster, but ’87, ’88, ’89, you start seeing a lot of college guys coming in, and there are very few, if any NASL players on those teams. That’s when Gansler took them and they started playing 20-30 games—if you look at a ’90s roster, you won’t recognize anybody from the NASL on that team.”

There’s a compressed, tangible progression at this time, from the NASL professional to a new generation of national team player, to World Cup qualification, a combination of “a little bit of American and international ways of playing,” as Kowalski put it, to getting out of a World Cup group, to MLS. It was the era where we earned the right to have expectations.

The career U.S. domestic professional also became a tenable thing. It’s one thing to look at the NASL and see Pelé, Beckenbauer, Best, Cruyff, Chinaglia and talk about the investment to get those players here, to build the game in America. But I wondered what it was like for a domestic player in the 1970s to look at that league and see a future. “When you dream about being a professional and you maybe someday hope you are, I thought maybe in my college days, that might happen, but that was really far off. Really far off,” DuBose said when I asked when he knew he’d made it. “Because a lot of goalkeepers in the NASL were European. When I thought it really might happen was when I got drafted.” DuBose was drafted fourth in the first round of the 1977 NASL Draft, by San Antonio (who moved and became Team Hawaii, putting DuBose and others in a dispersal draft, where Tampa Bay bought his rookie rights.) For juxtaposition, I asked Tony Meola the same question, and his response illustrates the power of Caligiuri’s 1989 goal. “Not until after we qualified for the World Cup in 1990,” Meola said. “During the [college] soccer season I had the keys to the indoor facility to go hit [baseballs] and I would go to soccer training, to study hall, and then I would go meet my baseball buddies in the cages at night and we would go hit.”

And then he said this: “I don’t remember the date, but I guarantee you, within three days of leaving for Cocoa Beach, for the Trinidad game, I was still swinging a baseball bat every night.”

Somewhere in the basement of the house I grew up in, there’s a Betamax tape worn thin just before and just after the 30th minute of the 1989 World Cup qualifier between the U.S. and Trinidad and Tobago, when Paul Caligiuri scored the goal that ended the 40-year drought. There’s no more iconic moment from this time than that goal. The Cocoa Beach Meola’s talking about leaving for is the week-long camp to prepare for that game in Port of Spain. In the early ’90s, I watched that tape over and over, but I had no idea that just days before, one of our most decorated goalkeepers was still hitting baseballs and going to the University of Virginia, because there were so few reasonable paths in soccer.

Caligiuri scored, the U.S. went to Italy ’90, hosted the Men’s World Cup in 1994, made the round of 16, and MLS arrived in ’96. Things shifted.

“When I first arrived [in the U.S. in 1976],” said Brian Tinnion, who scored the first NASL 35-yard shootout, “people asked me how long before soccer takes off here. I said 10 years. I said the same thing in 1986.” And when Tinnion attended a 1994 World Cup group-stage draw between Brazil and Sweden, with seventy-seven thousand in the Pontiac Silverdome, he realized it had finally taken off. “I knew then, this was it.”

The game belonged to a new generation, one that might be able to make a living playing, but also that benefited directly from the one before it. All these guys who grew up watching the NASL were playing alongside and replacing the previous generation’s players. In their interviews, the MLS players referred to specific NASL moments: Vermes mentioned growing up with the NASL, Wynalda talked about a Cruyff LA Aztecs shootout goal as the best one he’d ever seen. Jeff Agoos watched the Dallas Tornado and New York Cosmos.

“I was a Cosmos ball boy,” Tony Meola said. “I was at every Cosmos game there was.” Meola told me a story where he and his best friend Sal Rosamilia snuck out of school and went to Giants Stadium to get into Cosmos training. Security guards were denying them entry, “and Pelé came over and said ‘No, these guys can come in.’”

:02 // “But 95-98 percent of the country had never had a soccer ball kicked on it, and that was the difference we set out to change”

Clive Toye

Ron Futcher’s worst memory of the 35-yard shootouts begins with Futcher’s Minnesota Kicks beating the Cosmos 9-2 in the 1978 Eastern Conference semifinals. In any aggregate home-and-home situation, going into Game 2 up seven goals, Futcher’s team would be all but ensured of moving on, even after the Cosmos won the return leg at home, 4-0. But, in the 1978 NASL, aggregate didn’t matter. The series was tied 1-1.

The ensuing mini-game yielded no goals, so a shootout it was. After five shooters, each team had scored once. It would come to one shooter each until there was a winner. Minnesota’s sixth shooter, Alan Merrick, was stopped by Cosmos goalkeeper Jack Brand. The next shooter was New York’s Franz Beckenbauer. “Beckenbauer never showed any nerve,” Futcher says of the moment. “He just put the ball down, took a touch, took a step, knocked it out of his feet and scored, and that was it. We were out, and they were in the final.”

On video, it’s an iconic soccer moment, the ball hitting the net, Beckenbauer with arms raised, a capacity Meadowlands losing it as Cosmos players pile onto each other, a moment definitive, finite, and glorious: Der Kaiser sends his Cosmos on to the conference finals and an eventual Soccer Bowl championship.

Purists and pundits who champion tradition above all else likely have something to say about how this all went down, about how it wasn’t fair with Minnesota not getting the benefit of aggregate. And that’s a fair point. But consider what happens if the Cosmos, in 1978, the first year post-Pelé, go down that year to Minnesota. Does it affect soccer in this country in 1979, 1991, 1996, 2020?

The NASL of the ’70s faced a tremendous challenge similar to MLS in the mid-’90s: educating while entertaining. Both were equally essential, and the only advantage MLS may have had is that its domestic players and many of its fans had had a major league prior. NASL had to deal with a sport that had, with isolated exceptions, one American generation.

Clive Toye, then general manager of the Baltimore Bays of the NASL-predecessor National Professional Soccer League, was asked this question by a reporter at the 1967 title match between Baltimore and the Oakland Clippers: “So if you beat them, you’ll be world champions will you?” “No mate,” Toye responded. “I’m sorry…”

Though education was a challenge, so was infrastructure, specifically shared-use stadiums and narrow fields. Even in 1996, MLS fields only had to be a minimum of 50 yards wide and 100 yards long. (Now, the minimum is 70 yards wide.) In the ’73 season, the NASL instituted a 35-yard offside line, designed to counter similarly narrow fields and open the game to the chance of more goals. Over the next few seasons, other experiments evolved into the running shootouts from the 35-yard line if a game was tied after regular time and a 15-minute sudden-death period. Ted Howard, who was with the league “from birth to death,” said even team owners had problems with the offside law. The now-retired former CONCACAF Deputy General Secretary says of the NASL that people “were learning the game as they went along (buying franchises) as well. Most of the people were new to it and very frustrated with the offside law.”

FIFA had previously granted the NASL permission to experiment with adding a 35-yard offside line. “And then the shootout came after that,” said Howard. “Because we had this 35-yard line across the field, this became the new line, so that people could push forward. While we were experimenting with the line, somebody said the [kicks from the mark] shootout is terrible, because we had a rule that every game has to have a result. So we created this new shootout.” With the 35-yard line already present, the timing of the shootouts was not arbitrary, either. It was determined through testing that five seconds was a good amount of time to safely force action while protecting players.

John Carbray, who passed away during the time I was writing this story, was one of the people who created the shootouts. He helped convince league owners to approve them by providing proof of concept. In a July 1978 article in the Alberni Valley Times, Murray Greig writes, “Carbray [then Diplomats GM] has said that when the shootout was first proposed at a league meeting, it met with nothing but negative reaction. However, once team owners had a chance to see it demonstrated on film, it was unanimously adopted.” That film came from Carbray and a few Diplomats players trying different things at a college field in Maryland.

Carbray’s motivation as he developed the shootout was to entertain. “The American system is that you win or you lose,” Carbray said in a Daily News article from April 26, 1977. “Fans don’t leave with a good feeling if they see a game with no conclusion reached. And you have to please the fans.”

“Let’s have a go,” Brian Tinnion recalled was his attitude when he first heard about the shootouts being incorporated in the NASL. “We’re in America, let’s try it,” he said.

Greg Vanney understood too, without completely needing to buy in. “My initial thought [about the shootouts] was more excitement for the fans—when you’re trying to start a league, more excitement is better, because more excitement is more emotion. More emotion, you get attached to it,” Vanney said. “But from a traditional soccer standpoint, I wasn’t a huge fan of it, but I understand trying to create more excitement.”

Jeff Agoos has a “special fondness for the shootout.” But don’t expect it to reappear. “It was fun, we enjoyed it,” he said, “but at the end of the day, today we’re probably more aligned with the world’s game.”

When Marco van Basten mentioned the possibility of considering a shootout a couple years ago, when he was still with FIFA, Agoos was contacted: “Such a unique way to do it—at some point, the International Football Association Board asked, I provided some feedback to them in terms of what the experience was, what the protocol was, to give them a better sense of it. He (van Basten) was the guy I sent everything to.” But aside from some retrospectives and social-media remembrances, the shootouts remain in repose.

Safe to say, they are not coming back, and that’s probably OK. They’re a valuable reminder of times when soccer maybe needed something different to survive. When people wanted, above all else, to build the game in America, whatever it took. They’re fun, in retrospect, more game-like—and ours. We own the memories from when we all wanted something American, and we were willing to create our own space to get there; Our expectations now may seem more enlightened, yet they’re an organic eventual product of the work put in to build the sport.

The shootouts were but one mechanism in a larger purpose. “Those players in those early years, they spent half of their time doing community service and half their time playing for their club,” said Howard. “Without them going out and putting on clinics and selling the game, the game would not be where it is.”

And it was never just the players. Building the game was a full-time job in this country, often on top of other full-time jobs. “When I was with the Cosmos, I ended up coaching a team in Scarsdale because kids wanted to play, but their parents, none of them knew anything except the shape of a soccer ball,” said Clive Toye. “It’s a bit odd to think when you’re the president of the Cosmos and signing Pelé, sometimes I’d arrive home on a bloody plane with my luggage and not have time to go home before it was time to go straight to the field for practice. That’s how our thinking was in those days.”

That spirit existed in Meola and his contemporaries. “Most guys that played then, especially the guys on the National Team, through the ’94 World Cup, you basically had two jobs,” Meola said. “You had playing and trying to prepare, and doing whatever you could to promote the game. And it was non-stop, 24 hours a day. Meeting people, being at events, appearances, going to the gym. Most people thought they were at the beginning stages of something that could grow in the States one day. A time where soccer was growing every day. To play in the U.S. at that point, I was seeing it grow right in front of me.”

In the ’70s, in the ’90s, when it came time to build the game, everyone was on board, even if reluctantly. “You should have seen the looks on our faces the first time we saw the uniforms,” Eric Wynalda said of marketing meetings at the start of MLS. “It was like, ‘OK, here we go’.”

What can you accomplish in five seconds? How about 50 years?

“Ninety-five to 98 percent of the country had never had a soccer ball kicked on it, and that was the difference we set out to change. And of course it has changed…and it continues to change,” said Clive Toye. “Every time I walk past a store and see soccer stuff on sale or see a commercial selling something and what you see is a little boy kicking a soccer ball…it’s just normal American life now, and it was a weird foreign thing brought in by Commie midgets, as some newspaper in California told us. From Commie midgets to $15k for the World Cup to watch soccer, to where we are today is a significant, indeed a massive, change. You have no idea how much of our time with the Cosmos was spent not thinking about offside lines but, look, 35-yard offside lines and running penalties were hardly the most important things that happened to us. Getting kids to play and getting asses in seats were the two important things.”

:01 // “You have to earn the right to play”

Clive Charles

What can you build in 50 years? A league? Two? An enduring culture? From a college field in Maryland, a pile of balls with red stars inside blue pentagons, giving it a go, trying shit, starting from 35 yards? With Paul Caligiuri’s dipping goal, with Landon Donovan’s injury-time Algeria winner, with Brazilian legend Romario shaking Kasey Keller’s hand mid-game? With aspirations more than Dos a Cero?

So many who came to the NASL stayed and built. They coached. They shared the game. They did their bit. They remain involved, and those who learned from them do the same.

My son’s kids’ generation will be the fourth continuous iteration of the contemporary American soccer player, where expectations and culture could align, when the latter is properly primary. There’s a foundation. We’ve earned that. Those memories are ours, and now the game is theirs.

There are iconic moments, some cultural touchstones preserved in YouTube amber. But seeds are small, seemingly mundane memories, innocuous, like an impromptu kickaround in your living room or an in-season routine. Those last as well.

In Kansas City, Tony Meola drove to training every day with Peter Vermes and Kerry Zavagnin. He parked his Ford F-150 in the same spot after a short drive from the locker room to the practice field, next to where the then-defunct shootout clocks were stored at the Chiefs’ and Wizards’ training facility. “I always wanted to put one in the back of my pickup truck,” Meola said of the clocks. “That was a goal of mine.” He was going to do it, too.

“And then one day it was gone,” he said.

“Literally,

one

day…

it

was

gone.”

:00

The SHOOTERS

Peter Vermes (MLS) after a first touch, would push the ball out a little further, take a look at where the keeper was, and beat him to where he overcommitted. “You have to be clinical in your finishing,” Vermes said. The harder goalkeepers “don’t overcommit or go down early.”

Greg Vanney (MLS) liked to come at a slight angle with a long first touch 10-15 yards out “so I could keep my head up and see what angle the goalkeeper was going to take.” For his shot, Vanney preferred to “open [his] hips and curl it around off to the far side around [the goalkeeper] or show like [he] was going to curl it around him and try to bring it back to the near post.” More times than not, he went for the far post, and then it was just a matter of going high or low. “Most of mine,” Vanney said, “were setting the keeper up and setting the angle.”

Ron Futcher (NASL) said, “You’ve got to get the first touch out of your feet and then get your head up and see what the keeper is doing. I tried to start just off center, to the left, about 5-10 yards. As I knock the ball, I can open my body shape to try and curl the ball around the keeper from the left side on my strong foot, on my right foot. I was more comfortable opening my body. My first touch was just firm enough where if the goalkeeper came off his line, he’d be caught in no-man’s land, and I’d take a second touch.”

Peter Ward (NASL) liked to go about five yards, flick the ball up and lob it over the keeper. “Now and again, I change it up,” he said. “Go around him or place it past him, on the floor.”

Brian Tinnion (NASL) liked to “bend it with the outside of [his] right foot, to the goalkeeper’s right leg, down low.”

John Bain (NASL) didn’t always hit the ball at the same place, but, even in indoors, started the same. “Instead of going straight, I would get my first pass about seven-eight yards in front of me, angle to the right—because I take a right-footed shot—so by doing that,” he said, “I had a different angle, so the angle is different when I’m taking the shot, more comfortable for a right footer. Then take another touch and depending on the keeper’s position, I would side-foot it to the corner or chip him.”

Eric Wynalda (MLS) wanted to get the goalkeeper to commit. “The rule on that is…a goalkeeper, if you think about it, can only go down one way or another. They’re not going to fall straight down, or they’re not going to fall straight back, so they’re going to go to their left or their right at one point. So you have to go low hands or high feet. And I was always in the mind that once they committed to the ball that I would go over their feet. Because their feet aren’t going to be four feet off the ground. I would very seldom shoot to any goalkeeper’s hand side. I actually learned that from Brad Friedel, and he was right.”

Tony Meola (MLS—as a shooter): “My style was to try and score.”

The GOALKEEPERS

Tony Meola (MLS—as a goalkeeper) wanted to get to where the shooter would try to dribble him, to take time. “I was quick on my feet,” he said, “so the closer [the shooter] got, the better I am.” Meola was a “big target,” so the shooter would have to try to beat him with the shot or dribble him, which puts the advantage, especially with just five seconds, in Meola’s hands. “Breakaways were one of the things I did fairly well,” Meola said.

Winston DuBose (NASL) said the goal is to understand and limit “time and space. If you can restrict that, put pressure on them, [the shooter] has to make a decision.” It helped DuBose to know if the shooter was right- or left-footed, to “take the easy shot away. If they score, they’re scoring across my body.” Like Meola, DuBose was quick, so it helped him to put the shooter under pressure right away.

Scott Hileman (USISL) tried to get an angle, and “don’t get chipped, try to throw them off. As they’re about to strike the ball, you’ve got to have your feet set. That’s something I learned from Bill [Irwin] a long time ago. If you’re moving, it makes it easier for the shooter. So you just try to get out and get the best angle you can, make the goal as small as you can. Make them beat you. Try to understand their angle before they do.” The shootouts were “breakaway training,” he said, “and with Bill we’d go through them all the time at the University of Portland, so for me, I was comfortable with it.”

Bill Irwin (NASL) paid attention to the shooter’s first touch. “I had a little bit of speed. If I could read that first touch, and get out on it, then…you just try to stay up as long as you can to try and get that five seconds. There’s no time limit on us, the goalkeepers, but the field players had five seconds to get the shot off. So you just try to delay them. And then all you need is a touch.”

Separate & shorter essay, by the same author, on the indoor shootout:

RED LINES, MARADONA AND THE ARMADILLO

Part 1: Red Lines

Add any one- or two-letter combination in front of “SL,” and you’ve likely come up with the acronym for an American indoor soccer league. The Menudo of the American soccer world, an indoor league always seems to be in operation, rarely, however, in exact uniformity from league to league over time. MISL, WISL, NPSL, CISL, EISL or MASL: somewhere there’s a rug of turf thrown over an ice hockey rink, from Tacoma to Milwaukee, San Diego to Baltimore, with some Canton, Dayton, Turlock and Tallahassee in between.

Outside a handful of NASL-sponsored indoor tournaments and four somewhat proper seasons of NASL indoor that kept fans and players involved during outdoor down times, the central league that brought the game into the American mainstream was 1978-1992’s Major Indoor Soccer League. I loved the MISL during this era and watched Wednesday Night MISL on TV. Playing professional indoor soccer was something I wanted to do as a kid and did as an adult.

Until the ‘85 MISL season, running shootouts from the red line satisfied draws, and several indoor leagues since have handled penalties and shootouts thusly: shooter on the red line, goalkeeper on the goal line, five seconds to score. Anything from accumulated fouls to two-minute penalties to settling tie games, could warrant an attempt. Sometimes it was one-vs-one, as with its NASL outdoor sibling. Other times, it may have been merely a restart, where the non-shooting players started at the midline, one team in the circle, the other outside, the game live once the whistle blew.

There were perils with the indoor versions. “You had to know the rules, and you had to administer them,” referee Eric Beck said, for both referees and players. “Sometimes [players] would back up and kick the ball [from the red line]. We’d be like, what are you doing? You can dribble it.” But most shooters and goalkeepers eventually got it.

Another season-to-season alteration affected indoor shootouts: the shape of the box. Nick Vorberg recalled the larger arc being changed to a smaller box. “When the box changed,” he said, “I couldn’t go out as far because I’d lose the ability to use my hands, so my timing [during shootouts] was more important.”

Part 2: Maradona

Brett Phillips’s lengthy indoor soccer career included stops in St. Louis, Portland, Milwaukee, Harrisburg, Baltimore, and Kansas City. In my interview with him, he points out two anomalies that make the indoor version just that much different than the outdoor: The walls and other players.“The thing you had to keep in mind in indoor, as opposed to outdoor,” he said, “was if you got too far off the line, them passing it past you and receiving it off the boards for a tap in.” In indoor soccer shootouts, like outdoor, the shooter gets five seconds to shoot, as long as the goalkeeper doesn’t touch the ball first (barring the ball doesn’t go into the goal after the goalkeeper’s touch). And, like outdoor, the entire field is in play for those five seconds; however, unlike outdoor, indoor includes walls. Some shooters liked to get the goalkeeper committed to a quick close only to pass the ball off the wall to the side of goal and then to beat the keeper to the ball and still shoot before five seconds. It’s tricky for a shooter because of oddities in boards or the yellow plastic line that’s common at the bottom of hockey boards. So the ball could bounce anywhere, thwarting the shot.

“Shootouts during the game,” Phillips noted, “are live.” Once the shooter touches the ball, the game restarts. “Then the whole team is running from the half line, so you also have to take into account them just passing it to somebody, to their fastest person who just beat everybody down the field,” he said. “I was never a fan of that, and I let them know about it because to me, if you can’t beat me one on one, you don’t deserve a goal.”

Phillips had one specific shootout memory from 1995 that can’t be replicated. “I was with the [Continental Indoor Soccer League] and they took an indoor team to Mexico for the world cup of indoor. We played against Argentina and it was Diego Maradona’s first time back from his FIFA suspension,” Phillips recalled. “And he actually took a shootout against me. And that was extremely cool, to line up against Diego and try to figure out how to get in this guy’s head, based on who he is.”

Who among us wouldn’t want to utter the words, “And that was extremely cool, to line up against Diego” and actually be referring to Diego Armando Maradona?

“They blew the whistle, he wasn’t ready, he gets to do it again. He didn’t score, so that made me happy. It actually ended with a 50/50, me against him. It ended with a slide, and he didn’t get out of the way, so he lost that one.”

Part 3: The Armadillo

My Rosebud is a pair of black Mitre indoor soccer shoes with Tatu’s gold signature printed on the outside of each. After saving, I bought the pair from the pro shop at Portland Indoor Soccer, then the only indoor soccer facility in my hometown in the ’80s. When I got home, I discovered they were different sizes, with one shoe a half size too big. I called the shop to ask if they had the other of the correct size, and they said no. Somehow, the pair was lost, and they offered me a refund or a different pair of shoes once I returned them. I didn’t. I stuffed the toe of the larger one with newspaper and wore them until I couldn’t get my foot into the smaller one.

The importance of the shoes has everything to do with the name near the heel: Tatu. The Brazilian, known to most by his nickname (which translates from Portuguese to Armadillo) first arrived in the U.S. to play with Gordon Jago’s NASL Rowdies as part of an exchange with São Paulo FC. Jago, while in Brazil recruiting other players for the Rowdies, “saw this game going on on a basketball court, and Tatu was playing, and he was absolutely brilliant.” At 18, Tatu ended up playing the indoor winter season for Tampa Bay, his contract eventually bought for $30,000 (or twice what Clive Toye and Phil Woosnam paid for the 1970 World Cup TV rights).

I loved the indoor game so much I made my own field. My father sold real estate, and I took a stack of retired wooden for-sale signs from behind our garage, nailed them to 2x2s, and buried the bottom of the 2x2s in the ground along the perimeter of our backyard. With the addition of some turned-over benches and a pair of 4’ x 8’ truck sideboards that advertised a friend of my dad’s bid for Oregon state senate, I had my own “indoor” soccer field–with a flood light for night games, as well–that lasted a few years, at the sacrifice of any hopes my parents had of ever enjoying their backyard.

On my field, I often pretended to be Tatu. I knew of him from those Wednesday Night MISL Soccer broadcasts. I was him in the backyard field, and I was him in our basement with a taped-up Nerf ball, scoring goals and flipping my shirt to the crowd. Twice, for my birthday, my parents bought me tickets to see Tatu’s Dallas Sidekicks play in Tacoma against the Stars, a short two-and-a-half hour drive north.

When I eventually played my first professional indoor soccer game in 1998, for the Portland Pythons, it was against the Dallas Sidekicks. Nick Vorberg and Zack Chown, two of my best friends from college, were on the team with me, and there were just over 10,000 people in Reunion Arena. Tatu was the Sidekicks’ player-coach. I played against a childhood idol and realized a professional goal.

When I interviewed Tatu for this piece, I got a laugh out of him when I told him that I wanted to ask for his jersey that night but didn’t because, as a rookie, in a game we lost, I was too worried about my coach’s reaction. But I also got to tell Tatu about the shoes, and I got to tell him how much it meant to have him as the soccer player I wanted to be.

“That’s fantastic,” he said. “Those are the stories that make all worthwhile.”

The Indoor GOALKEEPERS

Nick Vorberg (Portland Pythons, Utah Freezz, San Diego Sockers, Milwaukee Wave): “I wanted to keep my feet, and I tried to get out as quick as possible,” Vorberg said, noting he left at the whistle, not the shooter’s first touch, to make the shooter “make a decision to dribble him or try to shoot.” If the shooter shot, Vorberg liked to be as close as possible to the shooter to try to get a touch, ideally by making the shooter shoot across his body.

Brett Phillips (Portland Pythons, St. Louis Steamers, Harrisburg Heat, Baltimore Blast, Milwaukee Wave, Kansas City Attack): “My philosophy was one of two things. And it was determined by the shooter’s first touch,” Phillips said. “If it was a long touch, my strategy was to get as close to their feet as possible, just to cut the angle down. If it was a short first touch, then I would stay back, forcing them to take that second touch, again mainly trying to get as close to their feet as possible and take away that angle, always trying to force them to shoot across my body, which means, obviously taking away the near post.”

Stuart Dobson (Portland Pride, Chicago Power, Buffalo Blizzard, Utah Freezz, Philadelphia KiXX, MIssissippi Beach Kings): “Because of the size of the goal, you could pretty much cover most of the goal, low with your feet, high with your hands.” Dobson’s strategy was to “rush out 3-4 yards, try and push the guy on an angle, cover the near post a little more, bend low, and try and get your legs to cover everything low and hands high. Guys would take one or two touches and hit with their stronger foot.” His philosophy also echoes his college goalkeeper coach Bill Irwin’s: “If the forward tried to dribble you, even better. The more touches they have, the more chances for a bad touch, more time for us to get a hand to it.”

Scott Hileman (Arizona Sandsharks, Edmonton Drillers, Florida ThunderCats, Baltimore Blast): “Get out and get the best angle you can. Make the goal as small as you can. Make them beat you. [The] burden is on the shooter to make the decisions. Stay big, look for a bad touch, a mistake.”

Both Dobson and Hileman mentioned the same challenging shooter to face. Drew Crawford “would touch it to his left every time, and he’d put it right over my left shoulder, every single time,” Hileman said. “One time I came out with my hand on top of my shoulder, and he pumped, and I dropped my hand, and he put it right over my shoulder again.” Dobson suggests one way to stop Crawford might be as simple as timing: “Basically try and move and get your face in there at the last second.”

The Indoor SHOOTERS

Drew Crawford (Denver Thunder, Arizona Sandsharks, Detroit Rockers, Detroit Ignition, Buffalo Blizzard): “I was a right-footed player, so I pulled the ball off to my left, to the goalie’s right, towards the top of the box. And the goalie would come out, and I’d let him get as close as he wanted to me because all I was basically doing, it wasn’t really a chip, but it was a soft shot over the left shoulder and they couldn’t get their arms high enough because their arms are down low, protecting for the low shot. So I just went over their shoulder.”

Peter Ward (Tacoma Stars, Cleveland Force, Wichita Wings, Baltimore Blast, Tampa Bay Terror): “I used to go around the goalkeeper,” said Ward. “Once at Wichita, for Cleveland, I went around the keeper and scored, and, to be honest, the clock was at like 6 or 7 seconds, and they counted it.”

John Bain (Portland Pride, Tacoma Stars, Golden Bay Earthquakes, Minnesota Strikers, Kansas City Comets, St. Louis Steamers): Same as outdoor but with a “shorter touch and not try to chip him.”

Rob Baarts (Portland Pride, Portland Pythons, Utah Freezz): “I always pulled it to one side to see if the keeper changed his angle and then I’d open up my body and I’d either bend it around him or pull it to the near post,” he says. “And I did that every time. You can’t really catch onto it because if you think I’m going to pull it, I’ll just bend it around them. I’m going off of their movements. I’m hoping they’re trying to read what I’m doing.”

Tatu (Tampa Bay Rowdies, Dallas Sidekicks, Wichita Wings): “Come in at an angle at the goalkeeper” because it’s “easy to finish across my body to the back post. As I approach the goalkeeper, I’m coming to his left side. If he moves, he’ll give me the back post, which I was good at. In case he does not move, and I’m reading the situation, if he doesn’t close, he will give me the first post open. It was basically a split-second decision while I’m dribbling. In case he overcharges me, I can extend the touch, and I clear him, and I have an open net. If you can catch the keeper moving forward as you strike, you’re going to score.”

To Felix, for whom I kept the game. And for those who came before us, who built and shared it here.

Contributors

Billy Merck

Billy Merck signed his first professional contract for indoor soccer’s Portland Pythons, in a career that also included stops with the Utah Freezz, Cascade Surge, Lafayette Lightning, and Louisiana Outlaws. An NAIA All-American at Pacific University in Oregon, he was inducted into their Hall of Fame in 2013 and holds the Boxers’ all-time career assist record, which he set in 1997—not bad for a left back. After playing, Billy completed three Masters degrees, including his MFA from McNeese State University, and his PhD from Washington State University. He writes about soccer and lives in the Portland area with his wife and son. Twitter: @billymerck.