Fields up to 200 yards long, a prohibition on forward passing, and, tragically for those of us who love a good howler, no goalkeepers—these are just some of the features of soccer’s original rules, the 14 laws of the game set down by Ebenezer Cobb Morley in 1863. What else would surprise us today?

Goalposts were fixed eight feet apart, as they are now, but there was no crossbar to connect them; and it didn’t matter how high the ball traveled—as long as it passed between the sticks, it counted as a goal. When the ball went out of bounds, whoever touched it next won the right to put it back into play no matter who had kicked it over the line. Teams switched sides every time a goal was scored. Players were not allowed to carry the ball or pick it up off the ground, but they could snatch it out of the air—a“fair catch”—or grab it on the first bounce. Catching the ball entitled the handsy player to toss it to a teammate or take a free kick, “provided he claims it by making a mark with his heel at once.” The only time one could pass to a teammate upfield was on what we now call a goal kick, which meant that the process of advancing the ball looked a lot like rugby, with a single brave soul charging forth before dishing it laterally or being tackled and losing possession—so long as the defenders did not violate Law No. 10, which stipulated, “Neither tripping nor hacking shall be allowed and no player shall use his hands to hold or push an adversary.” And lest we begin to think play was more genteel back then, it was apparently necessary to explicitly outlaw “projecting nails, iron plates, or gutta-percha on the soles or heels” of boots.

For all the ways it has become more complex in the century and a half since these laws were codified, soccer is still a simple game (though it’s not for lack of tinkering). And we explore the ways that soccer has changed in Laws of the Game (pg. 42), a compendium of the minor tweaks, wholesale changes, lasting improvements, and utter failures that successive generations of administrators have made to the rules of soccer.

And in Inside Gianni Infantino’s Evil Plot to Expand the World Cup and Make FIFA One Billion Dollars (pg. 36), journalist Jamil Chade throws that conversation into the future by examining FIFA’s recently approved plan to enlarge the 2026 event to 48 teams—a change that will just so happen toweaken the quality of the soccer while further enriching FIFA. How do we know this? FIFA admitted as much in an internal document that we are now publishing. We’ve long known that FIFA operates like

a greedy, gluttonous beast—the subject of our cover art by Peter Zierlein—rather than in the best interests of the game and the billions of people who love it. But the publication of this report shows that FIFA’s members made this particular decision knowing that it prioritizes profit over the preservation of the World Cup as the sport’s premier event. And so we are learning that the Gianni Infantino era won’t be all that different from the mess that preceded it.

It is thanks in part to the politicking of Sunil Gulati that there is a Gianni Infantino era at all. The president of the U.S. Soccer Federation has emerged as a key power broker in world soccer since he joined the FIFA Executive Committee (now called the FIFA Council) in 2013. TV cameras showed Gulati working the room at the FIFA Congress in February 2016, when he switched candidates and helped whip the votes that elected Infantino on the second ballot. Noah Davis profiles him in FIFA 101 (pg. 64), showing how Gulati juggles his teaching duties at Columbia University with the far-flung demands of his various soccer gigs, and poses a question that may define the Gulati era of American soccer: if the United States and its neighbors win the right to host the 2026 World Cup, will that victory justify decades of working within FIFA’s rotten system?

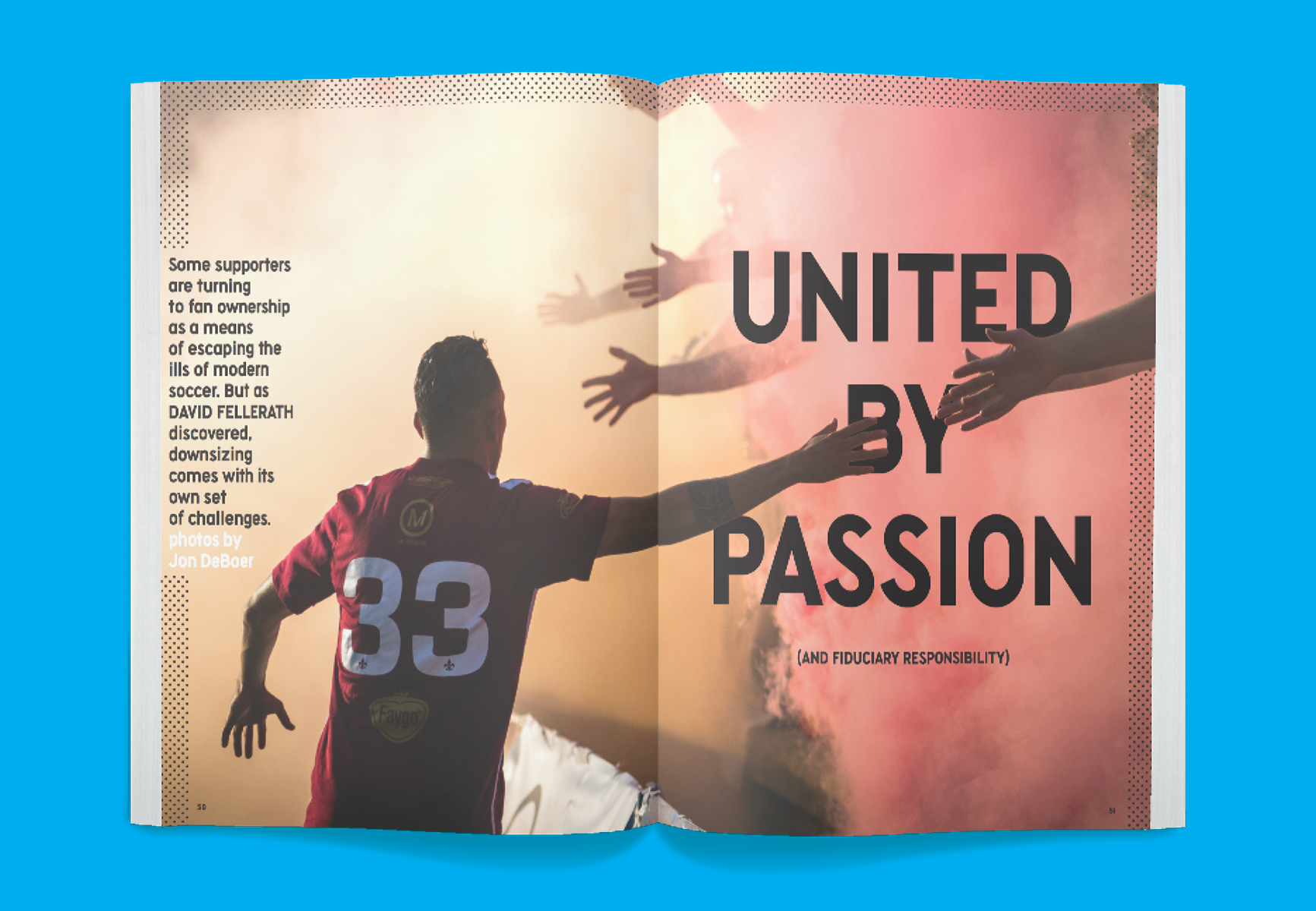

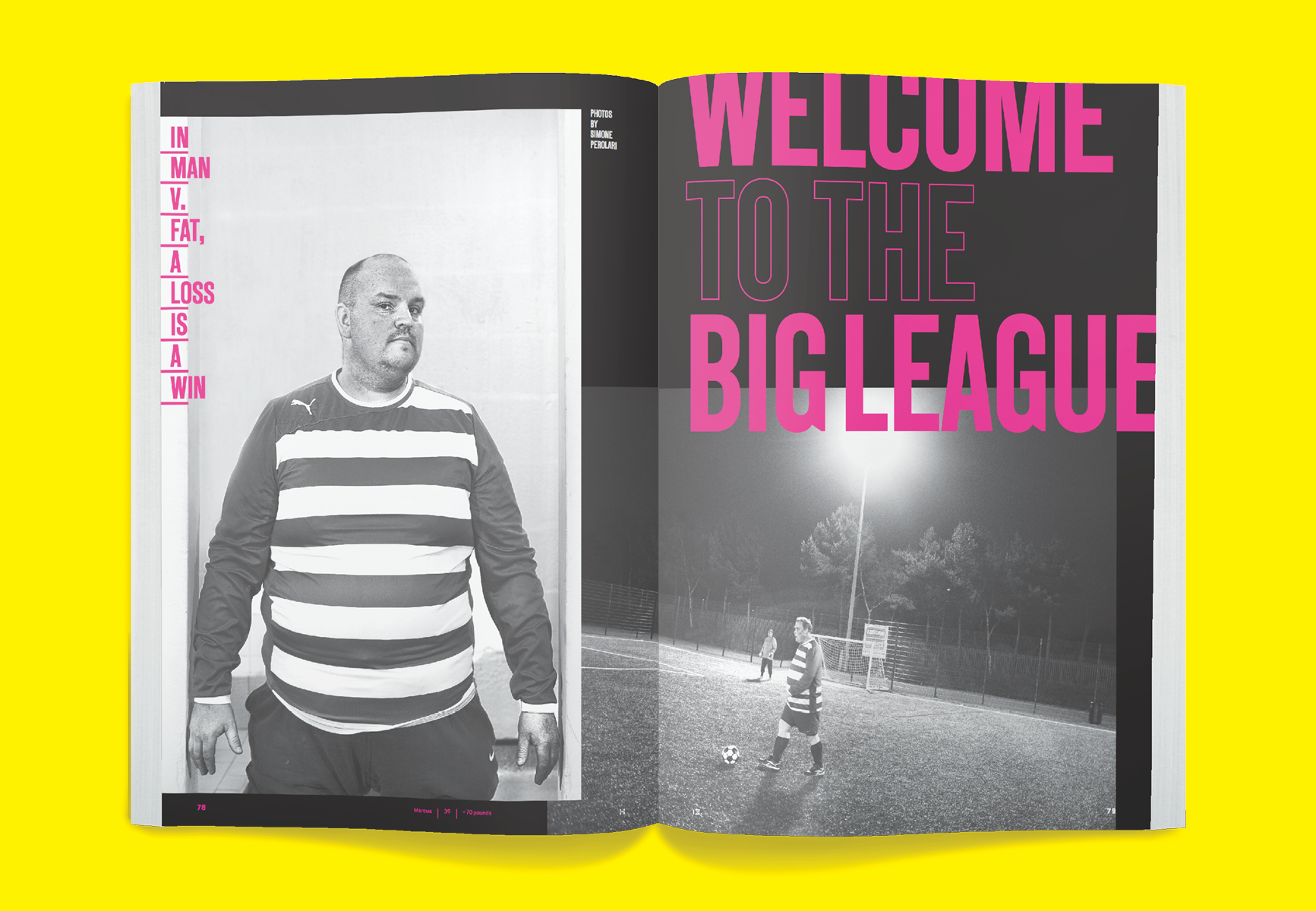

For those seeking an antidote to soccer’s ongoing corporate takeover, we train our focus on the other end of the spectrum in three stories. In United by Passion (and Fiduciary Responsibility) (pg. 50), David Fellerath profiles a selection of supporter-owned and fan-invested clubs like FC United of Manchester and Detroit City FC. Photographer Simone Perolari last brought us a photo essay on Florence’s ancient game of calcio; now he’s back with Welcome to the Big League (pg. 78), an inspiring look at a weight-loss program that is helping men across the U.K. shed pounds on the soccer field. And Match Dispatch focuses on the Oving and District Villages Cup, which has been contested by the small towns within a 12-mile radius of Oving, about an hour north of London, since 1889 (Battling Biff-Bangs and Bangs in the Gob, pg. 26).

Five years ago, a Georgetown sophomore named Sam Patterson became Howler’s very first editorial assistant. Now, I couldn’t be more proud to publish his first feature, an impressively reported story on the Beitar Jerusalem supporters group La Familia (Chaos on the Right Wing, pg. 58). Its members pride themselves on being the “most racist” fans in Israel, and they’re a big reason that Beitar is still the only Israeli club never to field an Arab. But their hateful practices finally caught up to them last year when dozens of La Familia members were arrested in a sting operation that resulted in drug and weapons charges.

Two members of Team Howler have recently published books, and we’re running selections from both of them in this edition. In The Backup (pg. 84), Bobby Warshaw writes about the feud with his manager at FC Dallas that ultimately resulted in his move to Sweden—a fascinating behind-the-scenes glimpse of player-coach relations of the kind that rarely becomes public. And Dennie Wendt’s comic novel melds an alternative-history 1970s American soccer league with a plot involving Soviet espionage (This Is Bloody Football, pg. 98).

We round out the issue with a few pieces that shine a spotlight on soccer in our country and region. Howard Megdal gives a blow-by-blow account of the New York Cosmos’ near-death experience this past winter in Thrice in a Lifetime (pg. 92). On the occasion of MLS’s 21st season, Phil West has lovingly collected some of his favorite moments in the life of the young league into a baby album of sorts (21! on pg. 70). Finally, you asked for more coverage of our region, so we’re introducing a new Open Play section called CONCACAF Briefing (pg. 18), where we’ve collected updates on Canada, Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean from some of our favorite experts on soccer in those places.

As we finish Issue 13, the Gold Cup is winding down and we’re starting to look forward to the endgame of World Cup qualifying. Things are going to ramp up from here, so I’d like to plug our family of podcasts and the redesigned www.whatahowler.com. That’s where we get to respond to the news of the day, squabble over Bruce Arena’s squad selections, and shake our heads about FIFA’s latest shenanigan. But for now, turn the page, take a break from the news, and don’t worry—they’ll still be trying to ruin the World Cup when you get back.