While he’s laughing all the way to the bank, the rest of us are miserable

Alan Pardew is the new West Bromwhich Albion manager, and at this point we might as well face facts and make our peace with the reality that the slimiest of adult failsons will be managing in the Premier League until the end of recorded time.

We all know what’s coming: A slight bump in form, plenty of ingratiating interviews with friends in the press, a modest win streak that provokes talk of moving on to better jobs, pining for players from the 2012-13 Newcastle side, and the inevitable, months-long slide that Pardew has repeatedly proven incapable of arresting that will eventually lead to his ouster. Been there and done that. We all know this script just like we know the corresponding ones for David Moyes, Sam Allardyce, Roy Hodgson and all the usual suspects repopulating technical areas in the lower half of the Premier League.

It is fitting, then, that Pardew’s first match in his new post was an eminently forgettable nil-nil draw against Roy Hodgson’s Crystal Palace. Both men previously managed the opposite side. Tony Pulis, late of Unemployment FC, previously managed both teams. (Don’t kid yourself; He’ll be back in a couple weeks.) A tweet did the rounds this week tallying all the clubs that have employed some combination combination of Pardew, Pulis, Moyes, Allardyce, Hodgson, and maybe even Mark Huges at the helm, but who can really tell the difference?

It’s not even worth trying to differentiate the members of this Brexit focus group. They’re easier understood as one long-term manager blocking the ascent of managerial talent, both domestic and foreign. These retreads are wont to join clubs in or around the relegation zone and leave them a year later in or around the relegation zone. Their only real skill is temporal: when the music stops playing and the season comes to the end, they tend to be near a spot just over the drop.

Over any time horizon longer than six months, they leave you on the verge of relegation, no better than when you first hired them. (Of late, Sam Allardyce has solved this problem by resigning at season’s end and getting a new job a few months later.) While they move from one job to a next, the reality is that the same few jobs are just being reassigned within this clique of dinosaurs. We can therefore look beyond their short tenures at any given club and recognize their true blight on the footballing landscape: years of turgid mediocrity with precious little to show for it.

Other than obnoxiously rich managers in this de facto cartel, it’s hard to imagine very many people who are happy about this arrangement. Fans, who quickly tire of these dullards, have to live with stultifying play and constant fear of relegation and minimal expectations. Any joy at liberation from a manager like Tony Pulis is wont to quickly be tempered by the arrival of Alan Pardew. World-class players are subjected to managers who were shown to be limited a decade ago and insistent on having their trusted deputies at every club. Neutrals and fans of other clubs are bored to tears. Owning a football club probably sounded fun to men like West Brom’s Guochuan Lai, but the grim reality is that it amounts to replacing Tony Pulis with Alan Pardew.

The financial élite who own football clubs do not merit our sympathy, but it’s still worth pausing to note that the Premier League’s riches do not even appear to have made them happy. Most clubs now exist in a desperate scramble to secure another year of TV money and then…well, not much. If you can afford to own West Brom, you can surely also afford a cable package that will quickly reveal the existence of many exciting sides in other leagues that were assembled for a fraction your soporific survival candidate. That must be galling.

While most Premier League clubs and their owners may feel like paupers in a world that contains Man City, Real Madrid, and PSG, the rest of the world correctly understands that the likes of Crystal Palace and West Brom are actually insanely rich clubs. (Both entered the top-30 of Deloitte’s Money League in 2016.) Accordingly, when these clubs try to buy an exciting player they are made to pay a premium. Once signed, those exciting players are often ruined by the need to survive for another year of TV money before once again being good when they leave England. Everton is paying Sam Allardyce more than the managers of three of last season’s four Champions League semifinalists to, at best, finish seventh and eke into the Europa League if top-four clubs win the FA and EFL Cups. The best-case scenario for many Premier League owners is to hang on long enough to sell their club to someone richer who will quickly inherit the same basic misery.

If you just want to become richer, a football club is not the place you should be putting your money. It’s the kind of investment that only makes sense if you think ownership will be fun and satisfying. But even with that kind of investment, there’s an incipient paranoia that sucks out all joy. The prospect of losing money or status appears so overwhelming that these men—and they tend to be men—seem to lose the capacity to think about anything else. The existence of charlatans in the football world scares owners off anything but the most known of quantities. Like parasitic financial advisors, an owner must now pay a chairman who will somehow find a way to recommend Alan “but really I’m a DILF” Pardew in 2017.

What happens to owners is the footballing equivalent to a billionaire art collector selling off all their paintings because they were swindled once and henceforth only shopping for prints at Ikea. (Other than the Ikea bit, this is actually what happened with Monaco’s Dmitry Rybolovlev.) The comparison to an Ikea print flatters Alan Pardew, but that is the upshot of this analogy. All there is to look forward to for these owners is another year of TV money. At the point where you’re that concerned about ROI, you might as well have just put your $300m in a passive fund and gone to an island on vacation.

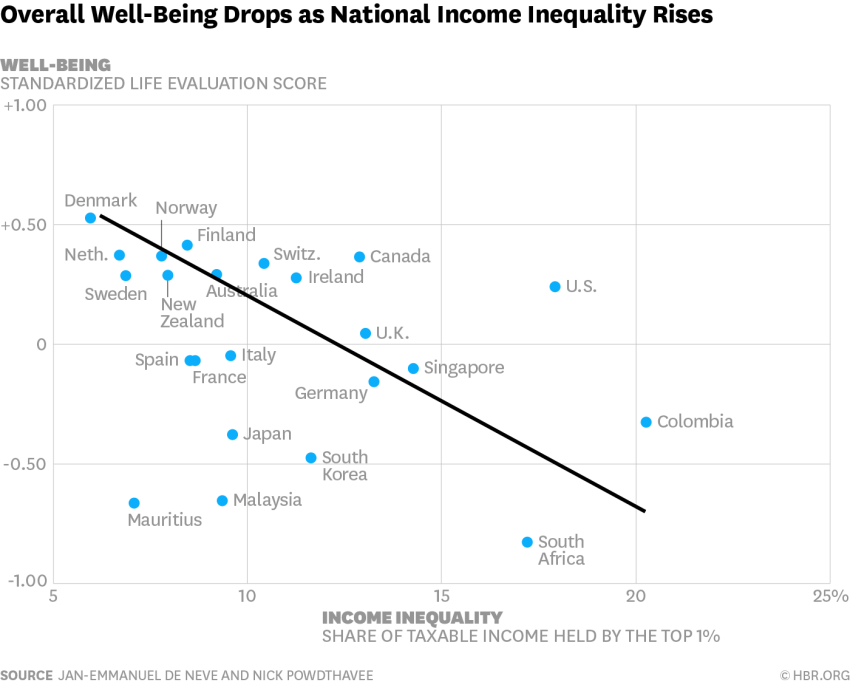

It is not a particularly unique or football-specific observation to note that riches do not translate into happiness. Social science research on the subject suggests that the accrual of wealth is not really a recipe for happiness. “People grossly exaggerate the impact that higher incomes would have on their subjective well-being,” writes the Princeton economist Alan Krueger. Other economists, like the University of Warwick’s Andrew Oswald, have noted that relative status is what changes contentment: “when everyone in a society gets wealthier, average well-being stays the same.” This is a good way of understanding what happened to the Premier League in the last few years. Clubs like Crystal Palace and West Brom became much richer but their position vis-à-vis the Manchester duopoly remained the same and so everyone remained miserable and put-upon. Another big TV deal may come in a few years but none of this is going to change.

The solution to this problem, while radically unpopular with the élite, is not exactly a mystery. European football in general and the Premier League in particular have built a profoundly unequal system that should be demolished for everyone’s good. After 25 years, the Premier League should be properly reintegrated into the Football League structure and the massive earnings of its haves—West Brom and Crystal Palace very much included—should be properly redistributed to the actual have nots of British football.

Instead of pushing to lock in the status of European football’s aristocracy with a super-league, income from European competition needs to be better divided among participants and handled in such a way that it doesn’t create mini-leagues within domestic competitions like the Premier League’s top-four fixation. For good measure, just tax all the wealth involved far more aggressively. This was always the morally righteous course of action, but maybe the happiness argument has a better chance. If the gaps between the Premier League and the Championship, between the top-six and the rest of the league, or between the European super-clubs and everyone else were smaller, clubs and their owners might actually have fun and not spend all of their time fretting over the relatively inconsequential difference between 18th and 14th or fourth and fifth. Such structural change would also help obviate the need to hire a rotating cast of alleged fixers like Alan Pardew or Sam Allardyce. None of this will ever come to pass, of course, because the rich would rather be as rich as they are now and completely miserable than slightly less—but still quite fabulously—rich.

Some of the richest people in the world set out to buy football clubs because they thought it would be fun and cool only to end up hiring Alan Pardew. This outcome would be darkly humorous if these millionaires weren’t dragging us all down with them. The world is rich with joyful footballers and the rich are using football to make everyone miserable.

Follow David on Twitter @DavidSRudin.