Hint: It’s Not All Jurgen’s Fault

Editor’s note: This story appears in the Spring 2016 issue of Howler. You can support the magazine by subscribing here.

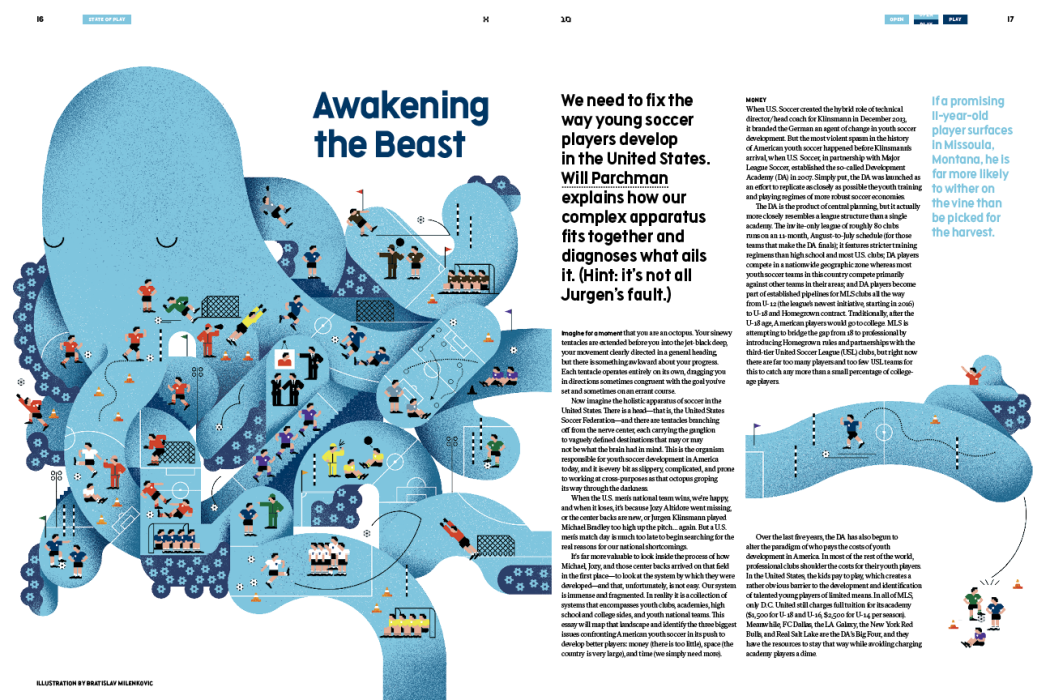

[I]magine for a moment that you are an octopus. Your sinewy tentacles are extended before you into the jet-black deep, your movement clearly directed in a general heading, but there is something awkward about your progress. Each tentacle operates entirely on its own, dragging you in directions sometimes congruent with the goal you’ve set and sometimes on an errant course.

Now imagine the holistic apparatus of soccer in the United States. There is a head — that is, the United States Soccer Federation — and there are tentacles branching off from the nerve center, each carrying the ganglion to vaguely defined destinations that may or may not be what the brain had in mind. This is the organism responsible for youth soccer development in America today, and it is every bit as slippery, complicated, and prone to working at cross-purposes as that octopus groping its way through the darkness.

When the U.S. men’s national team wins, we’re happy, and when it loses, it’s because Jozy Altidore went missing, or the center backs are new, or Jurgen Klinsmann played Michael Bradley too high up the pitch… again. But a U.S. men’s match day is much too late to begin searching for the real reasons for our national shortcomings.

It’s far more valuable to look inside the process of how Michael, Jozy, and those center backs arrived on that field in the first place — to look at the system by which they were developed — and that, unfortunately, is not easy. Our system is immense and fragmented. In reality it is a collection of systems that encompasses youth clubs, academies, high school and college sides, and youth national teams. This essay will map that landscape and identify the three biggest issues confronting American youth soccer in its push to develop better players: money (there is too little), space (the country is very large), and time (we simply need more).

• • •

MONEY

When U.S. Soccer created the hybrid role of technical director/head coach for Klinsmann in December 2013, it branded the German an agent of change in youth soccer development. But the most violent spasm in the history of American youth soccer happened before Klinsmann’s arrival, when U.S. Soccer, in partnership with Major League Soccer, established the so-called Development Academy (DA) in 2007. Simply put, the DA was launched as an effort to replicate as closely as possible the youth training and playing regimes of more robust soccer economies.

The DA is the product of central planning, but it actually more closely resembles a league structure than a single academy. The invite-only league of roughly 80 clubs runs on an 11-month, August-to-July schedule (for those teams that make the DA finals); it features stricter training regimens than high school and most U.S. clubs; DA players compete in a nationwide geographic zone whereas most youth soccer teams in this country compete primarily against other teams in their areas; and DA players become part of established pipelines for MLS clubs all the way from U-12 (the league’s newest initiative, starting in 2016) to U-18 and Homegrown contract. Traditionally, after the U-18 age, American players would go to college. MLS is attempting to bridge the gap from 18 to professional by introducing Homegrown rules and partnerships with the third-tier United Soccer League (USL) clubs, but right now there are far too many players and too few USL teams for this to catch any more than a small percentage of college-age players.

Over the last five years, the DA has also begun to alter the paradigm of who pays the costs of youth development in America. In most of the rest of the world, professional clubs shoulder the costs for their youth players. In the United States, the kids pay to play, which creates a rather obvious barrier to the development and identification of talented young players of limited means. In all of MLS, only D.C. United still charges full tuition for its academy ($1,500 for U-18 and U-16, $2,500 for U-14 per season). Meanwhile, FC Dallas, the LA Galaxy, the New York Red Bulls, and Real Salt Lake are the DA’s Big Four, and they have the resources to stay that way while avoiding charging academy players a dime.

But that’s MLS. The DA also includes roughly 60 clubs that are not hooked up to the league’s money pump, clubs that charge players upward of $2,500 per year. Shut off that spigot and you shut down the club itself. In this respect, the pay-to-play system is what pays the coaches and keeps the system from collapsing in on itself.

The lawsuit filed by Seattle club Crossfire Premier brings the difference in systems into sharp relief. Crossfire is suing over unpaid compensation from former player DeAndre Yedlin’s sale to Tottenham Hotspur by the Seattle Sounders last year. Yedlin spent two years with Crossfire before joining the Sounders for a single season at the U-18 level. He then played college soccer at Akron and joined the Sounders’ senior team. MLS pocketed his transfer fee from Spurs in the January 2015 window, blocking even a small chunk of it from filtering back down to subsidize Crossfire’s operation despite the fact Yedlin spent twice as long there as he did in an MLS academy.

If the U.S. federation is going to wean its youth setup from pay-to-play, then enforcing so-called solidarity payments is an obvious first step. Crossfire’s suit practically begs FIFA to open up the American structure to a more accurate compensatory system for non-MLS youth clubs. And the vast majority of youth clubs in the U.S. — we’re talking in the 99 percent range — are non-MLS clubs. It could be the beginning of the end for pay-to-play.

• • •

SPACE

If U.S. Soccer, and MLS by proxy, is the octopus’s head, U.S. Club Soccer (USCS), U.S. Youth Soccer (USYS), and the USL represent the most muscular tentacles. The USL is the country’s third-tier professional league, and it is increasingly being used as a stepping-stone to MLS for players in the U-18 to roughly U-23 age groups. All non-DA players younger than 18 play for clubs that are members of either USCS and USYS, the two biggest youth soccer organizations in the U.S. Together, they encompass hundreds of clubs and millions of players from U-6 to U-18. This scale is what makes the prospect of a single technical director benevolently ruling over all this territory with the assistance of just nine full-time scouts so comical.

But that’s the task Klinsmann has assumed. He, along with his scouting staff of nine plus roughly 100 part-timers, is expected to keep tabs on the brightest talents at every stage of youth development in our continent-sized country. Many smaller European nations have many times that number of scouts with far less ground to cover.

So where do they look? The DA, of course, but it is folly to imagine that all of the best players in the country are housed among its teams, none of which has been in the league for more than eight seasons. An initiative called id2 is another place. Established in 2004 by USCS, the id2 program is a series of invitation-only training camps that brings in U-14 players from USCS’s own National Premier Leagues — not unlike the DA in their setup — based on the recommendation of its own coaches and scouts. U.S. Soccer officials attend and scout these camps.

The best players are culled from each of these camps, pooled into a single team, and sent on an international tour to play against other top youth teams in places like Italy, Argentina, and the Netherlands. The initiative is still too young to have produced any capped internationals, but Christian Pulisic, a U-17 youth national team star and prized prospect at Borussia Dortmund, had his first major international exposure on the 2012 team.

Beyond that, U.S. Soccer’s skeleton crew of scouts plays a reactive game of chasing the rumor of good players, scouring a handful of big tournaments each year, and praying that the good ones don’t fall through the cracks that have become chasms over decades of disinterest.

If a promising 11-year-old player surfaces in Missoula, Montana, he is far more likely to wither on the vine than be picked for the harvest.

In countries like Germany and Argentina, coaching education centers have turned out knowledgeable adults to guide future generations of professionals. This ensures that young players cannot advance very far without developing a grasp of formations, tactics, and proper training methods. Granted, much of the infrastructure has been provided by the professional clubs themselves, enabling the best players to be identified and developed by experienced coaches at the club level before they move up the ladder. That system still has not fully taken root in the U.S. If a promising 11-year-old player surfaces in Missoula, Montana, he is far more likely to wither on the vine than be picked for the harvest.

As beneficial as the DA has been, and as much as it has improved over the past five years, U.S. Soccer is still flailing in its attempts to bring the rest of American soccer into its orbit. There is not enough money, not enough eyes on players in tournaments, not enough youth coaching education, and not enough centralization to overcome what the U.S. currently lacks.

• • •

TIME

Criticism of American youth soccer development has largely been wedded to criticism of Klinsmann since he assumed his technical directorship, and that is not entirely fair. The country is vast, and the resources needed to make substantial change are not, as yet, available to him.

Qualified and passionate youth coaches taking U-8 and U-10 and U-14 players through their paces at a high level: This, more than anything, is what the U.S. lacks when compared with the world’s top nations.

Nor has he been idle. Under Klinsmann’s stewardship, the U.S. for the first time established U-16 and U-19 national teams to help bridge the chasm to respective U-17 and U-20 World Cups, where the U.S. has rarely performed well. Having smoother development pathways between those two age groups is paramount for the sake of continuity, and we are finally seeing that happen. U.S. Soccer has also launched a handful of training initiatives designed to improve its woefully lagging youth coaching system, including a Youth Technical Director course, an introductory F license to inculcate new coaches into the system, updated E through A licenses of escalating depth, and a new Pro license.

Yet Klinsmann has done little to deflect the broadsides. When he was hired in 2011, he spoke lovingly of engendering a proactive playing style in U.S. youth national teams, and now that we are years into his tenure, it is clear that this task has eluded him.

The problem is finding a fair test for gauging U.S. Soccer’s progress as a developer of youth talent under Klinsmann, if such a thing is even possible. If we go by U.S. performances in the U-17 and U-20 World Cups, there is not much to laud. The U-20 team made the quarterfinals of the 2015 World Cup (after going three-and-out in 2013), which was a fine achievement on its own. But the U.S. was tactically naive going forward and relied on frantic defending for the entire tournament. The results were good enough; the soccer was not.

The U-17 national team, arguably more important because it rests in the fattest part of a player’s developmental bell curve, has been a disaster since 2011. Under coach Richie Williams, the U.S. missed the tournament entirely in 2013 for the first time ever, and it played poorly en route to a winless three-and-out showing at the World Cup in Chile in October 2015. Stars like Pulisic and center back Danny Barbir will go on to brighter things, but the back half of their two-year cycle was a wasted opportunity.

Any real, substantive change will be engendered on the ground level with qualified and passionate youth coaches taking U-8 and U-10 and U-14 players through their paces at a high level. This, more than anything, is what the U.S. lacks when compared with the world’s top nations. Klinsmann is the Grand Pontificator, but he spends little time with youth players on an operational level. Upping requirements for youth coaches, regionalizing training, creating more partnerships with non-DA leagues and teams, hiring more scouts on both part-time and full-time levels — all these things will help.

There is no quick fix. A country so large with so many sports competing for a young player’s interest has development issues that will outlive most of us. Fans long for the U.S. to produce our very own Leo Messi, but Messi was originally developed by a club located in the town of his birth in Argentina. He didn’t move to Barcelona until he was 13. The system in which Messi first thrived was in place before he was even born.

Will Parchman is a staff writer for Top Drawer Soccer. Follow him on Twitter at @WillParchman. Bratislav Milenkovic is an illustrator who lives in Belgrade. Follow him on Instagram at @bratislavm.