The Only United

September 10, 2022

Billy Merck considers the legacy of Clive Charles, who left West Ham in the early 1970s for the North American Soccer League and ended up an American coaching legend. In some ways, that’s a journey a lot of men took then. Except that Clive wasn’t anything like any of them.

This is part three of a three part series. You can read part one here and part two here.

Here’s a Clive Charles Soccer Story.

His first assist in the United States came in the 79th minute of a 2-1 Portland Timbers’ North American Soccer League loss to the Washington Diplomats on June 24, 1978. Down two goals, on the road in front of 10,816 at RFK Stadium, left back Charles’s long ball found the head of teammate Pat Howard, whose redirection across goal reached Clyde Best, who slotted the seemingly consolation goal past Diplomats’ keeper Bill Irwin.

Yes, that Bill Irwin. But there’s more.

That assist in a 2-1 loss? It gave the Timbers a point in the standings. In 1978, an NASL win was worth 6 points…and each goal up to three was worth one—a scoring system which meant there was always something to play for, even if the win might be out of reach. Certainly, 2-1 down with 10 minutes to play still meant a chance at all 6 (or at least overtime or a 35-yard shootout, if the Timbers could just find a second). Yet, the eventual point the Timbers did take from that match helped them finish the season with an absurd 167 points from 30 matches, second in the Western Division of the National Conference, to Vancouver’s 199.

We could get weird with The Soccer, if we want.

The goal Charles assisted on also set the Timbers and Diplomats on course to meet in the 1978 NASL playoffs’ first round, where the Timbers exacted their revenge when Portland’s John Bain scored with just 49 seconds left in overtime. Bain, Portland’s NASL all-time leading goalscorer, finished a rebound past Diplomats’ goalkeeper Bob Stetler. Stetler had subbed on for the aforementioned Bill Irwin in the 77th minute because—I kid you not—Dips’ coach Gordon Bradley needed another North American on the field. According to Steve Kelley’s August 10, 1978 report in The Oregonian, Bradley had “inserted [South African attacking midfielder] Andries Maseko for American Carmine Marcantonio. That left Bradley with only one North American on the field,” so the Pennsylvania-born Stetler made his only career NASL-playoff appearance, replacing Northern Ireland international Irwin to keep the NASL-minimum of North Americans in the match.

The NASL was its own breed of cat, that’s for sure. And the players who participated, who were here to build the game we love today, just rolled with it all. In any other league at the time, in fact, Charles’s assist to Best, via Howard, wouldn’t even be an assist.

On his West Ham United first-team debut on March 21, 1972 away to Coventry City, pretty eerily the same thing happened in a 1-1 draw as, according to the Daily Mail’s Jeff Farmer, “Clive Charles, 20 year old making his debut at left-back, floated a cross into the goalmouth, [where] Pat Holland, another newcomer, headed it back and Clyde Best hammered his twenty-second goal from 20 yards.” So if you’re a stats person: Clive Charles-Pat Holland-Clyde Best in England in 1972: not an assist for Charles. Clive Charles-Pat Howard-Clyde Best in America in 1978: an assist for Charles. The reason has less to do with Pat surnames than it does the fact that it was the NASL who initiated the use of secondary assists in the sport. Soccer was certainly different not so long ago, at least in the US.

But then again, was it? It’s a ball, and it’s players. More important, since feeling is first, it’s the collective experience that reminds us how we all have more in common than we don’t, and we can see that when we share soccer stories.

Take Bill Irwin’s response 43 years after that June ’78 Timbers-Diplomats match, when I asked him if he knew his longtime friend’s first assist in this country was against him:

“No, I didn’t know that,” Irwin said. Without missing a beat, he laughed, “And I don’t think [Clive] did either, or I never would have heard the end of it.”

That’s the thesis: The love in Irwin’s laugh—even across all those years—a laugh and a moment that brings the past and present together, the way stories do, a moment that reminds us that Clive Charles is still handing out assists.

“For people who are young or did not know Clive,” Jeff Agoos told me, “it’s hard to see a name or read a story about him [to know]. But the most compelling part about Clive was he just cared, he had a huge heart. Portland was such a big part of his life.” The National Soccer Hall of Famer continued, “He represented not only the city, but also the area, and, to a larger extent, our country, and he was what is good about everything that’s in that city, and really everything that’s good about the game.”

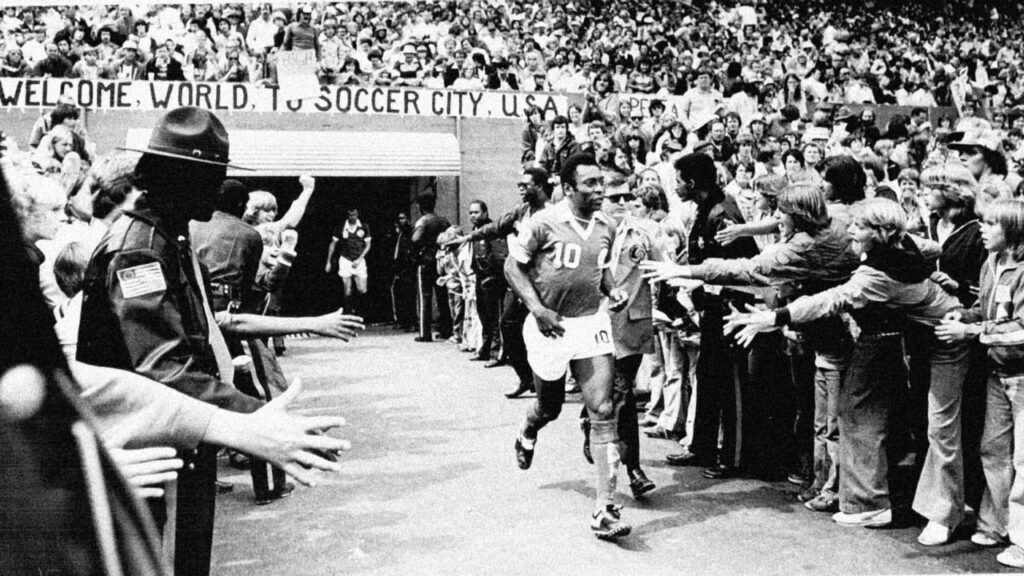

Joy is so important. Google “Ade Coker’s West Ham debut at Crystal Palace from 1971” and witness the pure happiness of the 17-year-old scoring. Keep it running until you see Clyde Best hug him in the celebration, and you’ll know what this is about. Find Tony Betts’s 1975 golden-goal header for the Timbers that won their first NASL playoff match against the Seattle Sounders. The then-injured Betts looks anything but, and his happiness is amplified by the throngs of fans storming the Civic Stadium field. While you’re in 1970s Portland, in that stadium, consider Pelé.

The Brazilian named by FIFA Player of the 20th Century, an award he shared with the late Diego Maradona, is as big a name as there is in the game. The English will never forget Sir Bobby Moore the way we Croatians will forever celebrate Luka Modrić. Outside of their home countries and diaspora, however, they may eventually require context. But internationally, across the game, the globe, and generations, Pelé will always translate.

In the last competitive match of his career, on August 28, 1977, Pelé’s New York Cosmos defeated the Sounders in front of 35,548 to win the NASL’s Soccer Bowl, sending the legend off with the last trophy he hadn’t until then won. Pelé, shirtless and holding the Soccer Bowl trophy in the air, was carried off the turf of that same Civic Stadium on the shoulders of fans, a fittingly dramatic end to the competitive career of the world’s best.

That same location is home to a great beginning, too.

That same location is home to a great beginning, too. On May 16, 1981, Betty Ellis became the first woman to officiate a professional soccer game in the United States when she served as AR as the Timbers hosted the Calgary Boomers. “I knew that I was opening a door,” Ellis told Michael Lewis for his 2021 article “She Ran the Line,” on US Soccer’s website. “I thought of other women that I knew who were interested in reffing. I felt the responsibility on my shoulders to do not just a good job, but a real good job, so they would have the opportunity when it came to them. That responsibility was really big.”

Among the moments big and small, the things that happened to happen on that site since 1893, the most current iteration, as Providence Park, will likely be most known to future generations solely as the home of the Portland Timbers and Thorns. Just recently, I went there with my wife and son—a section next to the Timbers Army, feet from the tifo, inhaling green smoke of a Timbers goal, my son meeting Timber Jim and Timber Joey. That match was the 136th meeting of the Timbers and Seattle Sounders across all competitions. Not a bad lineage considering West Ham and Millwall have met 99 times, dating back to the first meeting between Thames Iron Works and Millwall Athletic in 1899. Given that the Cascadia Derby started in 1975, that many meetings are quite impressive, especially when we’re talking about collective culture. Time, place, and people matter.

Jim Rilatt’s dad was part of the original Timbers ownership group in 1975, and that meant a young Jim would grow up around Civic Stadium in the nascent days of Soccer City, cleaning locker rooms, helping match officials, and serving as a ball boy. “I remember Civic Stadium and [that] Soccer Bowl, the Cosmos versus the Sounders,” he told me. Also among Rilatt’s early memories were doing what any tween boy in the ’70s might, given free rein to a stadium: “I remember, after games, digging under the bleachers because you could bring pop cans [into Civic Stadium] and they were a nickel,” Rilatt recalled. “I’m digging up bags and bags after we got everything cleaned up before the stadium crew got there.”

I, for one, love that the coach who led the U23 Portland Timbers to an undefeated season and the USL Premier Developmental League championship in 2010 was, as a kid thirty-plus years prior, digging around the same stadium for candy money.

“I was really blessed to have grown up in Portland and the soccer scene there.” As someone who’s seen the change, Rilatt has a first-hand, multi-generational perspective, and he was close to the most contemporary transition. “Merritt [Paulson] came in buying a baseball team, and there was a soccer gig going on,” Rilatt said of the current Timbers and Thorns owner. “And then he fell in love with it when he saw one of the exhibition games. There were like 15 or 20 thousand. The Timbers Army was in full song and, you know, it’s hard not to get swept up in the emotion.”

When Paulson bought the team, at the initial press conference, which even he admits was primarily baseball focused, he told me, “somebody from the Timbers Army” scarved him and “a side conversation happened [where] Clive’s name came up.” It’s not the first time he’d heard of Charles, but it was the start of understanding. “When I was out here, living and breathing it,” Paulson said of the city’s soccer lineage, “[Clive] stuck out because he played with the club. And with the club being one of the relevant clubs in the NASL, it’s a big part of why Portland is Soccer City, USA.” Among the clubs that have that roughly 50-year history, the Timbers do well to acknowledge the founders.

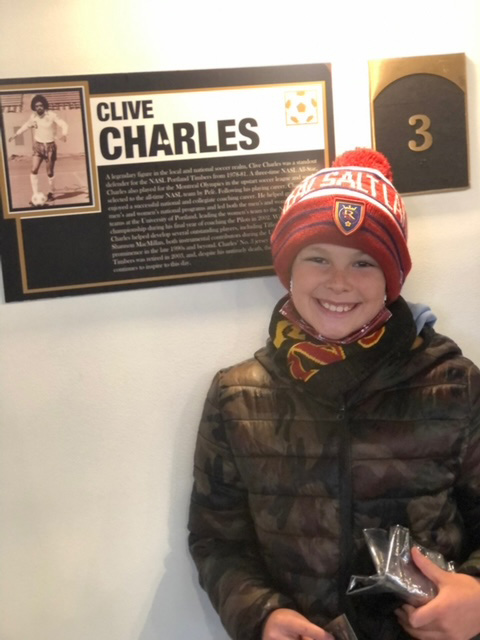

“I look out my office window every day and I see the names of John Bain, Clive Charles, Jimmy Conway, Timber Jim, and Mick Hoban,” Paulson said, referring to the Ring of Honor at Providence Park. “I am a custodian,” he said of the traditions and culture that predates himself and so many. “We definitely give a lot of credit and deference to the work that was done during those [NASL] years and laying the foundation for Portland soccer.” That deference, a visitor to the stadium might notice, is manifested in the myriad murals embracing the club’s history.

Clive Charles’s #3 is the only number retired by the club.

There’s a plaque featuring Charles’s likeness on suite 3 at the stadium, a location of pilgrimage for Brian Dunseth whenever Clive’s Olympic captain is in town calling matches for Real Salt Lake. “[Clive] was the father figure that a lot of us didn’t have,” Dunseth said, pointing to Charles’s impact in that regard, compounded by “how important and empowered” players who played for Clive felt. The impact is so significant to Dunseth, his middle son–Micah Clive Dunseth–is named for his mentor.

“[Clive] was the father figure that a lot of us didn’t have,” Dunseth said. The impact is so significant to Dunseth, his middle son–Micah Clive Dunseth–is named for his mentor.

And as of the writing of this, Clive is a finalist for the National Soccer Hall of Fame, a recognition that, in some ways, solidifies his legacy in formal halls–as it should. And these recognitions are important; it’s comforting to see soccer in the US connect to the NASL era and listen to the voices of those like Shannon MacMillan and Eric Wynalda who helped get Clive on the ballot, but there’s still something more essential.

“He’s a founder, he’s a builder. And he’s just a great person,” Jeff Agoos said. “It’s rare when you find people that have those types of qualities, not only in this game, but just in your life.” For Charles’s lasting impact, Agoos extended, “If you just look at the people he was around during his time, not only in Portland, but with the national team, we’re all branches from that huge oak that is Clive Charles, and we all grow roots from him and then those roots grow more roots and more branches, that’s what he established.”

I’ve tried to find a neatness to these narratives, to make connections. Not everything’s worked. I couldn’t quite link Clive’s last professional point (a 30-foot left-footed shot past Wichita Wings keeper Mike Dowler on April 5, 1983 when Clive was playing with MISL’s LA Lazers in the Forum) with Tiffeny Milbrett’s 100th and final goal with the US national team (which happened July 10, 2005, in the 57th minute of a match between the US and Ukraine at, of all places, Merlo Field, when an Aly Wagner long ball found Milbrett, who one-touched a left-foot loft over the keeper and into the south-end net, on the same field a college-sophomore Milbrett opened fifteen years earlier. “I came [to UP] because of Clive, not the facility,” the nonplused player told The Oregonian’s John Nolen at the field’s 1990 opening).

I couldn’t quite express a correlation between Clive’s retired Timbers #3 and the fact that any team photo of the University of Portland Pilots women’s soccer team between the years of 1994 and 1997 featured Clive’s daughter Sarah in the #3 shirt, that Clive’s son Michael played professional golf and now shares that game with others as a pro, that Clive’s wife Clarena is, to this day, President of FC Portland Academy, whose cornerstone philosophy is “Through the game of soccer there is an opportunity to prepare and develop young people for the challenges of life.”

But I can express thanks.

They gave their time with Clive, so he could give the game and so much more to others. He was an enabler who exponentially grew the soccer ecosystem.

Jim Rilatt was coaching at Portland’s Parkrose High School when he met Clive. “He had already started FC Portland. There was a group of players at Parkrose who were playing for FC Portland.” Clive was putting on a clinic for some players at an indoor center. “The parents introduced me to him and he looked at me and he goes, ‘I know you, you’re a University of Portland player,’ and I almost fell over and died.” Rilatt had played at the university before Charles arrived. At the time of their meeting, Rilatt said, “Clive was coaching ODP, so I asked him if I could just hang out, volunteer, do whatever, just so I can learn more. He said, most definitely. And I did ODP with him for a season.” Rilatt was smart enough to know the learning opportunity, and Charles was willing to share. “Then he asked me if I wanted to work his camps, so I worked there. And then he asked if I wanted to coach at FC Portland. And that’s where I met Bill Irwin.” From there, Rilatt went on to coach FC Portland’s first national championship team.

This is the trademark Clive Charles Story: Assists, providing an opportunity for others to be successful. And success begets success.

Dr. Kelsy Parker (née Hollenbeck) grew up just outside of San Francisco, and her club coaches told her about Clive and the University of Portland Pilots and the style of soccer they played, so she went to see the Pilots take on USF. “It was just amazing the way that they could play soccer,” she said of her first impression. “They kept the ball, they moved the ball really well. It was not a direct style of play. It was very technical and really beautiful to watch. So when I first saw them play, I was like, ‘Oh, my, that would be a dream’ [to play with that team].”

Hollenbeck joined the Pilots the next fall, in 2002. From the start, the first-year defender knew it was a special season. On one hand, it was awe-inspiring because alumnae like Tiffeny Milbrett would be around the program—”she’s someone we watched when we were kids, and she just there, kicking the ball and playing with us”—and on the other, it was empowering. The team integrated Hollenback and other first-year players quickly and seamlessly: “It was all about becoming a team [from the start of the pre-season]. It was a fantastic team—a ton of strong leaders in the senior class,” she says. “They immediately brought us into the fold.” By the end of that season, Charles’s last, Hollenbeck and her teammates would win the first national championship for the Portland program. Hollenbeck is just one of four players to play on both the 2002 and 2005 (Garrett-Smith-coached) national championship teams.

Given that 2002 year as initial entry to college soccer, Hollenbeck can be forgiven for thinking that type of success the rule. “It felt like this was normal. And then after playing on other teams, it was like, ‘no, that team was really special.’” Special because of what they did and who they did it for, but at the same time normal because the culture is representative of a Clive-Charles-coached team, of the overall ethos that creates a space for everyone in the game to thrive.

“I still coach today, because I love the game of soccer,” 70-year-old Brian Gant told me. Of his origins in coaching, Gant credits his relationship with Clive. “I’ve always loved it. But I happened to get pulled along by a guy who didn’t just love the game. This game was his life. I saw what he did, and I went ‘Wow.’ I started seeing how I was being influenced and how I was influencing the kids I was coaching. I was like, ‘This is great. It’s so much fun.’ And so when you think of Clive, he did that. He built the game by building players, but he also knew how to build a supporting cast.”

Given the history of playing together and how close Gant and Charles were, I thought Gant would have joined Charles and Irwin at the college level. But that wasn’t the best fit for Gant. “I was teaching and coaching Catlin Gabel (a school in Portland),” Gant says of the time in the 1980s. After Clive had been at UP for a few years, Gant remembers them having a conversation about college coaching. “[Clive] said, ‘you probably wouldn’t like coaching at college because you only coach the first few months of the year. The rest of the time you’re spending recruiting and you’re not coaching.’ And you know, personally I love coaching. I’d rather not be traveling around the countryside asking kids to come to my school to play.” Gant loved that he was able to teach at the school and coach. They’d just started FC Portland, so Gant and Charles discussed how Catlin Gabel was the right spot for Gant. They were right.

Gant’s Catlin Gabel teams won 12 of the first 13 girls’ state soccer championships at their level, including 11 in a row. (A related footnote: when the streak eventually ended, more than a decade after it started, the new state-champion-winning coach was University of Portland alumnus Scott Sagar.) The analog for that type of success in American soccer is the University of North Carolina women’s team who also won 12 of the first 13 NCAA championships, themselves running off 9 in a row.

During that run, Charles brought UNC to Portland in 1992, to expose his team to the best possible competition. They lost that match 6-1 but gained valuable experience and exposure. What many may not know is that the opportunity also reached beyond the players and fans.

Meredith Vanden Berg was the center official for that match. The Oregon native’s performance was noticed by visiting coach Anson Dorrance, and Vanden Berg was subsequently invited to center matches in North Carolina’s high-profile ACC. From there, she became the first woman to referee an ACC women’s championship match and both NAIA and NCAA Division I women’s championship matches.

None of this occurs in a vacuum. Examine any soccer culture in this country, and you’ll find stories like this. People tried to build the game in the ’70s and ’80s, some stayed and participated in other ways, their roots creating the life-giving impoundment we see in our soccer communities now. In Portland, it was the NASL Timbers who constructed the biggest dam, those names in the club’s Ring of Honor. We can see snapshots of the larger ecosystem, like the 1987 Oregon High School All-State Soccer teams, where those reading this essay will recognize then-senior Joey Leonetti and then-sophomore Tiffeny Milbrett as the boys and girls players of the year, respectively—not to mention Noleen Conway (the wife of Timber Jimmy Conway) as the girls coach of the year.

This is a community built from the all-hands-on-deck labor from NASL roots. It’s not an uncommon story in the US, though it’s not told enough. But, again, it is a little different in Portland because of Clive Charles. And it’s in the small things people remember.

Like the exactness of his video sessions. “It wasn’t the in-depth tactical stuff, which I have no doubt we did,” current Pilots women’s coach Michelle French remembers from her playing days. “It’s the simplicity” that translates to French’s coaching. She remembers a film session with a big TV connected to a VHS recorder and “our center mid had gotten the ball. I was playing left back at the time and Clive paused the video and he’s like, ‘Who are we missing? Who is missing in this picture?’ And the whole left side of the field was that beautiful Merlo pitch, very green. And there was no one there. And I put my hand up. I was like, ‘Me. I should be in the picture right now.’ And he says, ‘Yes.’ And that was the end of the video session. It was so simple.”

The coaching advice Jim Rilatt received about an issue once was equally prudent. Charles told him, “‘It’s like looking at a forest fire, there are a bunch of trees on fire. If you run around and try and put out every single one of them, they’re all going to reignite again. So focus on the most important ones and get them out, and then move on to the next one.’”

Clive’s advice was also useful for life. “You know, he said something to me one time that I can’t even imagine how many times I’ve applied it in my life,” Jeff Gadawski said. “He would say, ‘Listen, regardless the result at halftime, don’t be one of those coaches that uses the time to just go and scream and shout and try to get your players to do something special the next 45 minutes, because you might get it once, but it’s not sustainable. Be more articulate, think of the one or two things that if you possibly change or take a risk, might have an impact.’” Then Charles told him something that will resonate with any of his former players: “But more importantly, remember that when you don’t know what to say, say nothing and do nothing. Over the course of time, you’re going to get the right answer. You may not have the right answers at halftime, but you might get it when you’re driving home, you’ll be able to apply it next time.’”

Scott Hileman doesn’t specifically recall anything of formations or tactics Charles shared, but he does recall how it worked. “He would just say something to one player, like ‘hold your defensive line a little bit,’ rather than ‘Their outside back scares me.’” Instead of making it a thing the whole team needs to be concerned about, Hileman said of the simplicity, “he’d make that one tweak at the right spot. Looking back, after the game, I would recognize what he was doing.”

This is what I’ve been trying to do: look back and try to find the little tweaks here and there, where something made one person successful and then exponential movement from that epicenter affected others. It’s been a journey of hindsight benefitting from one person’s foresight. I’ve found in part, as well, that we are in a pretty special place at a pretty special time, straddling the NASL and MLS almost equally over the last 50 years, and a burgeoning, sustainable NWSL.

In part, it’s unique to region. “The Whitecaps and Sounders have a big impact on their collective soccer cultures,” Merritt Paulson noted of the Cascadia teams with NASL roots. “And specifically here in Portland, we’ve got one of the real rivalries in our sport today. And rivalries need history to really be real and have an edge, especially in the mind space of fans. And we have that with Seattle.”

Michelle French wanted to be a coach, and she found herself in the ideal position to do just that. She was in the US Soccer system, working with the national teams. “I felt like I literally had the best job in the world,” she said. “And if you would have asked me, there would have been no reason I would ever leave.” She was in such an ideal position that, when a coaching job at her alma mater opened, she had no interest in applying. But something compelled her to at least look into it.

“The big piece for me was just that I just wanted to do it for Clive,” she said. “I wanted to have the impact on these student-athletes that he had on me then and has on me every single day that I’ve been a player and a coach, so I wanted to do the best that I could to represent him, but also honor him and find a way to bring this program back on the map.”

I first interviewed Brian Gant for this just after he’d been interviewed by another writer for an essay about Clive. Katelyn Best (no relation to Clyde) had just spoken to the Canadian international for a piece titled “The House That Clive Built,” an excellent essay that explores Charles’s legacy specifically in context of the women’s game in Portland. Best had asked Gant about what he thought Clive’s legacy was. At the time, Gant said he couldn’t really put it into words. “I just said to her, he was a great person, a great communicator, and he treated people so well.” The interview had Gant thinking. “There’s so many things that could be his legacy,” he told me. But then it hit him. “I started thinking about it, and I started writing down who Clive coached and those players that he coached who went on and coached.” Gant continued. “Just basically, by memory, I came up with over 100 players Clive coached–just at FC Portland and UP.” Gant hadn’t yet considered the players in the US system. “That may be his legacy, that a lot of them will go on and coach very similar to his style.”

One of those players is Scott Sagar. “There are a bunch of great football players,” Sagar said, “but not ones that were influential to thousands of youth soccer players and humans. And I say that because soccer wasn’t the most important thing to Clive. He celebrated the individual. And then soccer and the success behind soccer, that was just a clever byproduct of having a trusting relationship, and a proper mentor. And Jesus we got lucky.”

“Honestly, the soccer part was just something that he happened to be good at,” Rob Baarts said. “That wasn’t his strength—his strength was you always wanted to play hard for him. He cared. And we knew he cared, and he cared for each person in a certain way that you knew it. He put everything into what he was doing, and he made you feel so empowered to do what you were doing.”

This is what happens when one person’s trail becomes others’ paths: legacy, lineage, culture.

And when it’s good, it’s perfect. “If I could have the impact that man had on me, even like 1/100th, on any of the kids I interact with, I will have done a good thing in this world.” That’s coming from Shannon MacMillan. And Kelsy Hollenbeck would add what this looks like. “His influence pops its way in every once in a while: once teammates come together and they do something together; when something is hard, but you know it’s the right thing to do, you do it. Volunteering, reaching out to the community, giving back: those are all things that he really emphasized, being a good citizen. And he lived it.”

“Actions speak louder than words,” Bill Irwin said, “Clive just went about his job. He rolled up his sleeves and was not afraid to get his hands dirty. He wanted to make his players better by first and most importantly making them better people.”

These messages continue, and that’s the story.

“I just can’t overstate that Clive was a great coach,” Tiffeny Milbrett said, “because he was everything: a great person, a great manager. He gave his players the game.” And for Milbrett and so many others, his presence is always felt. “Even to this day, like every single day, I think, what would Clive do? What would Clive have said? I think of him every single day.”

“The disappointing thing is there could have been hundreds and thousands of more people able to learn what I learned, and the game in our country would have been so much better and so much more advanced because of it,” Kasey Keller said. “I miss the phone calls, I miss the golf. [Clive was] one of the most special people in my life. Earl Chiles was very close in my life, as well. And Earl used to say it all the time: ‘Through Clive, we’re all together.’ And he’s 100% right.”

Through Clive, we’re all together. United.

Clive Charles’s biggest assist was to give so many the opportunities through the game of soccer, and, from that, he’s given us each other. Now it’s on us to share, to tell stories, to listen. To make others better, leave things better than we found them. Clive did his job.

In a Soccer America interview published in January of the year Clive passed, he told Scott French, “I owe so much to this game, I really do. I owe everything to this game.” Then he said the one thing I’ve found in any of this that’s been untrue:

“And I’ll never be able to repay what it’s given me.”

In 2018, Kasey Keller was on a panel titled “The Beautiful Game’s Global Reach,” at MIT’s Sloan Sports Analytics Conference, moderated by Grant Wahl. From a business and analytics perspective, the first three speakers were fascinating: a lot of information and talk about collection, organization, aggregation of data and then how to apply that to soccer-adjacent or -involved entities. It was everything analytics are: systematic computational analysis of specific information. Then Kasey Keller spoke, and the discussion became intelligent and human.

He listed off the teams he played for and their founding dates: Fulham FC (1879), Tottenham Hotspur FC (1882), Leicester City FC (1884), Millwall FC (1885), Borussia Mönchengladbach (1900), Rayo Vallecano (1924). “Pro sports is history. The Chicago Bears are not the Chicago Bears if they were founded three years ago.” Keller’s point was similar to Paulson’s: in this country, there are specific organic challenges we’re up against because of the relative youth of our soccer culture. However, we’re also in a better place than we may think, and people like Clive and his contemporaries are the reason why.

“When we were in the NASL,” Wilie Anderson told me of the 1975 Timbers, “we went out and did every kind of promotion you can think of.” Anderson estimated that team all together must have done “500 appearances a year, at least.” That’s a lot of time and work. I think of the Clive Charles quote, “You have to earn the right to play,” and I can see this as another instance of backing up what he says.

The hard work was a hallmark, and a minimum. Brian Gant talked about contacting middle and high schools in the area, to offer free soccer clinics. Clive, Brian, Bernie Fagan, and others would do free camps and, while they were there, hand out flyers for their proper summer soccer camps. “It became bigger than we ever expected it to be. It got to a point where the camps would sell out right away. But it all started going to schools, at a free soccer camp on the weekend.”

Clive et al had range, too. “Nobody was going to Forest Grove at that time, nobody’s going to East Portland,” Tiffeny Milbrett said of the areas outside the immediate Portland area. To her, those former Timbers were “providing opportunities for kids to get involved in sport. And, that’s what was so important about Clive’s environment, being a part of somebody so genius of the game but such an amazing human being.”

And it wasn’t just in and around the immediate area. Tracy Nelson met Clive in Everett, Washington. “He started doing a kind of academy up in Seattle,” she said, “where select players could come out and train with him once a week.” After the session, he’d drive back to Portland.

This isn’t a surprise to Clyde Best, who saw Charles and other Hammers in both the playing and coaching environments. “I would have put my money on [Clive] becoming a coach,” Best said. “He was a talkative person, wasn’t shy, and could express himself. He did what he wanted to do—became a football coach.” Best, who himself managed the Bermuda national team, also got his coaching start in those early playing days, working hard to spread the game. “When we were playing in the youth teams, we’d go to schools and coach.” He remembered going with Bobby Howe. “Bobby used to coach at the school level and he used to go there once or twice a week. And most people at West Ham, that’s how we were brought up, to give something back. Help other people along the way. Make it better for everybody.”

Make it better for everybody. This is something passed along through Clive. “No matter what it is,” Brandon McNeil said, “make it better, put it in a better place than when you got there. It could be your household, your community, it could be soccer. It’s important because it’s the right thing to do. Because you’re a quality person, and that’s the expectation that’s held of you.”

In these Clive Charles soccer stories, I keep ending up back at Tiffeny Milbrett’s words: vision, kindness, care, and love. And there’s another: legitimacy.

Tiffeny was inspired and instructed and had the opportunity to reach higher levels, and she recognized it—and recognizes how fortunate she was. “These guys were larger than life to us and to the fans,” she said of the NASL players who taught through camps and clinics. “From eight years old I had been influenced and coached by Brian Gant, Clive Charles, and Willie Anderson, and it’s important for me to have you encapsulate how legitimate and professional these guys were for the game. It was all for the player, it’s a product for the player, which is what soccer is supposed to be.”

“It’s important for me to have you encapsulate how legitimate and professional these guys were for the game.”

I wanted to write about Clive Charles because I’m thankful for what soccer has been to my life. Because I grew up in a specific place at a specific time, that’s what made sense. I went looking for stories, and I found them. Thirty-one interviews, over 20,000 words of final prose, and countless hours of research have, I hope, brought us all together a little more around Clive, around the game, around each other.

What’s hardest is how to be complete without being able to give you everything. But I can say, with absolute certainty, that we have a legitimate soccer culture, and it’s because of the people like everyone I’ve interviewed here and what they and their families gave to us through the game.

Personally, I don’t know if it gets better than the end of my conversation with Clyde Best. “I’ll always be biased when it comes to West Ham people because nine times out of ten, I know I’m getting a footballing person,” he said to me, talking about the club where he and Clive started. I told him I’m a West Ham fan and that I’ve recently started sharing this interest with my son.

“You’re a good man,” he said, enjoying the moment with a laugh not unlike Bill Irwin’s recollection of Clive’s first assist. And then he gave me a message to pass along to my son: “You tell him I said there’s only one united: West Ham United.”

Maybe it’s a stretch for us to reach beyond this, to think of a lineage from Thames Iron Works Football Club in 1895 to West Ham great Clyde Best and me talking football and passing along messages to the next generation in my son, but it’s at least plausible. The game is that great of a unifier—because we come together through stories, through people like Clive.

The game is indeed beautiful, and through that we’re all united.

Contributors

Billy Merck

Billy Merck signed his first professional contract for indoor soccer’s Portland Pythons, in a career that also included stops with the Utah Freezz, Cascade Surge, Lafayette Lightning, and Louisiana Outlaws. Billy played the three for Pacific University (Oregon) where he was an NAIA All-American and later inducted into their Hall of Fame in 2013; he holds the Boxers’ all-time career assist record, which he set in 1997. He also played and coached for FC Portland. After playing, Billy completed three masters’ degrees—including his MFA from McNeese State University and his PhD from Washington State University. He writes about soccer and lives in the Portland area with his wife and son. Twitter: @billymerck.

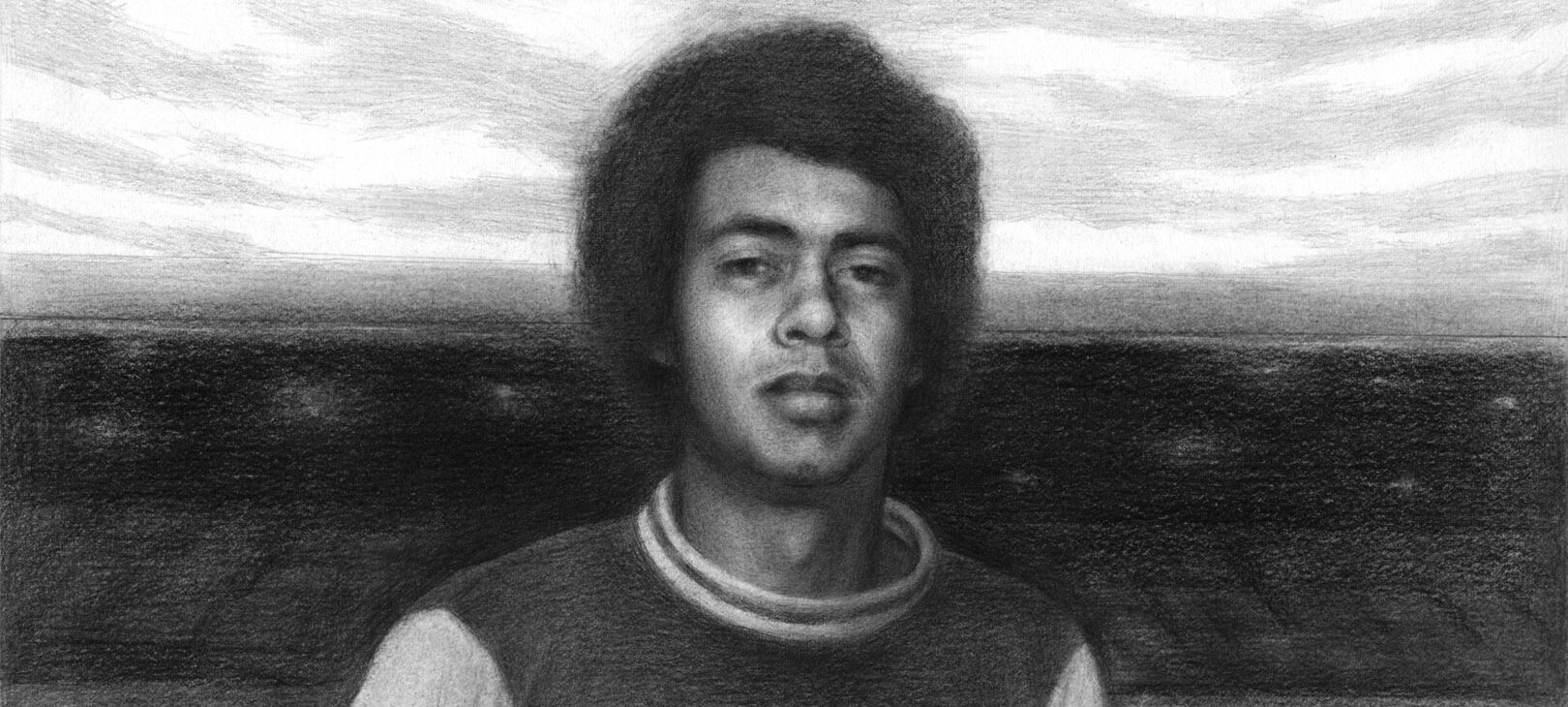

Maggie O'Keefe

Maggie O’Keefe is a painter and illustrator from Westchester, New York. She received her BFA from Cornell University in 2019 and studied at The Art Students League of New York. Maggie has exhibited her work at Dacia Gallery and her works are in private collections. She is an award-winning Junior Member at The Salmagundi Club and was a Finalist in The Portrait Society’s Future Generation Competition. Her instagram is here.

Creative Sponsor

Howler doesn’t have millionaire owners, just a determination to tell stories in and around the game we love that no one else would tell. Our sponsors make that possible by providing support for the writers, artists, photographers and contributors who are the heart and soul of what we do. Please support our sponsors.

This article is presented by Away Days Brewing Co. and they focused on creating the perfect combination of classic styles with English balance and European flair. The modern and intimate SE Portland taproom has ten rotating taps as well as two cask engines.

TAGS