From West Ham to the West Coast: How Clive Charles Quietly Built American Soccer

June 11, 2022

WORDS

Billy Merck

Illustration

Nick Iluzada

How one man ended up 8000 miles from home and shaped a soccer generation

Billy Merck considers the legacy of Clive Charles, who left West Ham in the early 1970s for the North American Soccer League and ended up an American coaching legend. In some ways, that’s a journey a lot of men took then. Except that Clive wasn’t anything like any of them.

This is part one, of a three part series covering the legacy of Clive Charles.

Tiffeny Milbrett called me one Friday afternoon. She was driving to the University of Portland, where she’d recently started as a volunteer assistant for her alma mater’s women’s soccer program.

Her name on the incoming call screen wasn’t entirely out of the blue. I’d interviewed her for this story a couple of days prior, and I assumed she was calling to say she found the DVD of a soccer skills video she’d told me about.

The video has to be nearing forty years old now. Here’s the basic premise: a group of boys, about my 9-year-old son’s age or just older, are at a field being put through the paces of some technical training. On a hill above the field, a diminutive girl watches them. At a certain point, the girl joins in and, following the simple techniques she’s observed in the training, executes, touch for touch, on pace with the boys who’ve been doing the drills.

As you’ve likely put together, Milbrett is that little girl. When she first told me about it in our interview a couple days prior, she cracked herself up with the absurdity of it all. I agree; it is pretty funny in its Coerver-Skills-Video-Meets-After-School-Special way. “Sort of corny.” That’s what Brian Gant said about the video he and Clive Charles made. Gant also added that Milbrett wasn’t the only recognizable name doing drills, that the boys in the video were mostly sons of former Portland Timbers, and that the video was supposed to kick off a series, just one of many ways Gant and Charles tried to teach and spread the game after their NASL playing days were through. Where the video world meets reality, however, prophetic might be a fairer adjective than corny.

That girl would not just master what Gant and Charles were teaching. She would go on to play club and college soccer for Charles, score 100 international goals for the United States, and win a World Cup as well as an Olympic Gold Medal. And now, she was back at the University of Portland, where she was enshrined in their Hall of Fame in 2012, a ceremony during which her speech included Milbrett saying what so many can echo of their own journey: “I really just owe all my thanks to Clive.”

Nearly two decades after his passing, those words still ring true for numerous others. Trying to succinctly communicate how and why has been a massive challenge. One minute, I can’t possibly understand how to tell you everything I want to tell you, and the next, I’m listening to Someone Significant take time out of their day to share a memory, a life lesson, a laugh. They’re doing it because of Clive and what he means to them, because they still hear his voice on the wind. There’s a range of memories and anecdotes I’ve collected through these conversations and the research rabbit holes that come after. I asked for 15-20 minutes of their time, and they gave me over an hour on average. Sometimes, more than once, like this example, where the player who scored the first-ever Women’s-Olympic-Gold-Medal-match-winning goal is calling me from her car not, as it turns out, about a rarely seen soccer skills video.

That girl would not just master what Gant and Charles were teaching. She would go on to play club and college soccer for Charles, score 100 international goals for the United States, and win a World Cup as well as an Olympic Gold Medal.

Milbrett arrived at the university only to be stopped by a security guard. I listened over the Bluetooth while they had a conversation. I should add that this was March 2021. Milbrett had just joined fellow Pilots alumna Michelle French’s coaching staff, just in time for the spring NCAA soccer season that had been delayed because of COVID-19. Campuses, along with many public places, were not fully open yet, so it makes sense any person arriving would be vetted–even at a very small college where that person’s larger-than-life likeness adorns the school’s most recognizable cathedral.

What can I help you with? (I’m here to prepare for the soccer game.) What’s your name? (Tiffeny Milbrett.) Are you one of the officials? (No, I’m one of the coaches.) For which team? (The University of Portland.) OK. You can park in one of those slots, but not those; those are for the officials. (OK. Thank you.) Milbrett apologized to me for the interruption and proceeded to park her car.

The University of Portland’s Clive Charles Soccer Complex is an amazing place: its soul is Harry A. Merlo Field, a beautiful soccer-specific stadium, with a lighted natural grass pitch and a seating capacity just south of 5,000. It’s the model for a college soccer stadium, one that would make many professional teams across the country envious. And wrapping the back of the east bleachers is a series of banners with the nearly 15-foot likeness of notable Pilots in action through the years, including Tiffeny Milbrett.

And, there’s the real Tiffeny Milbrett, at her alma mater as part of the coaching staff, at the soccer stadium where she’s literally on the building. Tiffeny could have easily pointed to her 15-foot self as proof of belonging, but she didn’t. She answered every question with respect. Person to person. Equals because each was doing her job, and, beyond the job, each is a person first. The respect was clear, and what the complex represents, as well as the interaction I unintentionally witnessed, are manifestations of the foundation Milbrett mentioned in her induction speech, just after she thanked Clive. The words she used then were “vision, kindness, care, and love.”

Tiffeny could have easily pointed to her 15-foot self as proof of belonging, but she didn’t.

“I wanted to call,” Milbrett told me, “because I wanted to say that it’s great that players now have all this.” I assumed she was motioning toward everything in front of her. “It’s great they have Merlo and the uniforms and the locker rooms and the lighted field and all that.” She paused. “But I had Clive.”

Not all love stories are soccer stories. But all soccer stories are love stories. These are Clive Charles soccer stories, from remarkable people who also just happened to be phenomenal soccer players. All of whom also had Clive. In their stories, you’ll find your own.

1: Clive Charles Came from West Ham

Now, Brandon McNeil is the Technical Director for United PDX, Oregon’s largest soccer club. Then, he was a US Youth National Team player out of San Diego’s Nomads Soccer Club, who called his dad from a recruiting trip to the University of Portland. “You did what?” McNeil’s dad said, “You committed? You have four more [recruiting] visits you can go on.” But McNeil knew Portland was the place to be, even when one of those would-be visits, Sigi-Schmid-coached UCLA, called him the next day. “[Portland] was the school,” McNeil said. “I knew that it was the community that I wanted to be a part of.”

Origin stories can tell us a lot about where a journey begins. Institutions, such as our soccer teams, often make it easy by putting the date of their inception on their crest. As individuals, however, we sometimes look for one moment the trajectory changed.

We sometimes look for one moment the trajectory changed.

Now, Shannon MacMillan is a National Soccer Hall of Famer who won a World Cup, Olympic Gold and Silver medals, US Soccer’s 2012 Female Athlete of the Year, and is a senior advisor to Landon-Donovan-coached San Diego Loyal SC, executive director of DMCV Sharks soccer club in San Diego, and founding investor in NWSL’s Angel City FC. Then, she was a 16-year-old from Escondido, California who already had her mind made up on another college when she decided there was no harm in taking a free trip to Portland since she had another official recruiting visit left. After a weekend with then-current players Tiffeny Milbrett and Molly Nakayama, the heavily recruited MacMillan sat across from Clive Charles, the coach she’d hardly seen her whole time during the trip. Of her previous recruiting visits to other colleges, MacMillan said, the sell was consistent: “These coaches were promising me the national team. Promising me that I was going to start every game, I was going to score all these goals, I was going to be amazing.” But her trip to Portland had a different pitch.

“All right,” Charles told MacMillan, “you know, we’ve kind of watched you, and we’ve talked to some of the players and we think you’ll be a good fit up here.” That was it.

“I remember looking at him kind of like, that’s great. And then I’m like, well, am I going to play?” MacMillan said. “And he looked at me with his little smirk and was like, ‘I don’t know.’ And I said, well, you’re the coach, right? ‘Yeah, I’m the coach.’ I said, So am I going to play? And he goes, ‘I have no idea.’” MacMillan at first thought it was some sort of joke. “‘Look,’ he goes, ‘I can’t promise you things like that. That’s up to you. All I can promise you is the opportunity,’” MacMillan remembers. “And he said, ‘You know, I think you’re someone that’s looking for a home, we think this place could be a home for you. And you’ll be given the opportunity, but it’s going to be up to you what you do with that opportunity, because I can’t promise that you’re going to score goals. I can’t promise that you’re going to play because I will do what’s best for the team, but you will be given an opportunity to earn it.’”

Those familiar with Charles know the phrase “You have to earn the right to play,” in its many applicable manifestations. It’s a truism that permeates his coaching. And we will talk about that later in this story, but this section is about where we come from. It’s about where we started. More importantly, it’s about what started before we started.

I can’t promise that you’re going to play because I will do what’s best for the team, but you will be given an opportunity to earn it.

Then, Cindy Kappes (née Griffith) was a grade-schooler playing soccer with two neighborhood boys in her Oregon City cul-de-sac when a lady running through her neighborhood saw her and signed Griffith up for her rec team, years before she would become Clive’s first female recruit at the University of Portland.

Then, Scott Sagar was an athletic would-be Marine before a post-Dallas-Cup-match discussion with his mom and Clive turned his trajectory toward a menacing Merlo Field #6.

She would become Clive’s first female recruit at the University of Portland

Then, Tiffeny Milbrett was a sports-loving girl tagging along with her single mom to sports fields across Oregon’s Washington County. Now, well, she’s Tiffeny Milbrett.

Then, Bill Irwin was a former professional soccer player, who’d left his education as an electrician apprentice when he signed a professional soccer contract at the age of 15 with Northern Ireland’s Bangor FC, and was taking education classes to get his Associates Degree at Portland Community College. He’d settled with his wife in her hometown once his twenty-year playing career ended in 1987. Irwin heard his former teammate was coaching at the University of Portland and went to see him. Clive asked Bill if he wanted to help coach. “I think I made about $1,000,” Irwin said of his first season coaching with Clive.

Then, the 16-year-old MacMillan sat across from a coach she’d hardly seen on her recruiting trip, the coach who promised her the paltry-by-comparison “opportunity to earn it.” And something resonated. “I don’t know if it was his sincerity of him seeing that, you know, I was looking for a place to be home…,” MacMillan said. “People tell you that as you’re going through the recruiting process, you’ll just know. And until I was sitting in that chair across from Clive Charles, I was like, how do you just know? And then I was like, well, this is it.” MacMillan continued, “From day one, Clive just really believed in me. And that man was always just an incredible rock and human being who not only helped me pick my head up and look people in the eye and have confidence in who I was as a person, but as a player as well.”

Do you know where your soccer comes from? If you really look, I’ll bet you find it’s a pretty good story. “[Clive] didn’t talk about his game,” Scott Sagar said. ”He would answer questions if anybody asked him questions. [As a player] I challenged him several times. And then I stopped.” Sagar pointed to the moment from a pre-match training. “We were like, 30 yards out, and Scott Hileman was in goal.” The team had been working on free kicks. “And I started harassing Clive. I’m about where the wall would be, and I said ‘Clive, you think you could bend a ball around me?’ And he looked at me, like, ‘Sagar, you silly little man. He’s left footed, but with his right foot, he whips a ball around my head and puts it in the upper V. Then, he grabs another ball, hits it with his left foot, whips around the other side of me into the V on the other side. And [Hileman is in goal] with his jaw dropped.”

Scott Hileman remembers, “He just sat there and took one step and then put it in the upper corner, ‘All right boys,’ Clive said ‘we’re done then.’”

These stories are out there, of Clive, of us. It’s important we ask. “I never heard any stories about his playing days,” Sagar lamented, “and it’s a regret that I could have asked and he would have told me.” Sometimes, when we have the truest thing, we never think to ask, and that’s on us. “Clive was from that school of, look, if I have to tell you that I was a big deal,” Kasey Keller remembers of his former coach, “then I really wasn’t a big deal.”

I’ll go ahead and say it: Clive was a big deal.

Now, you’re watching a soccer game on TV in the US–NWSL, MLS, US National Teams, it matters not–or in person at a youth field in Portland or Salt Lake City, a college field in New Mexico, the NEXT generation of professionals from Tacoma: someone involved in that soccer experience, the one you’re having now, is just a degree or two from Clive Charles, which means, when you engage the game, you are, too.

Then, Clive Charles was born in Dagenham, London, in 1951, and would follow brother John to West Ham United and some significant milestones in English football history, but the foundation of what he would achieve would come from home. “He was very close with his mom, and his brothers and sisters,” Jeff Gadawski told me. “We were like brothers,” Clyde Best said of his relationship with Clive. “We shared the same house with his mom. She helped make us who we are, by the way she treated us and the way she expected us to treat other people.” Among the many ways football parallels life is that culture is a foundation built from the top.

“I had no clue I was going to play that day.” That’s what Nigerian-born Ade Coker said about his October 30, 1971 West Ham debut. Because the Hammers were away to Crystal Palace, the then-17-year-old Coker was along as one of the 15 allowed on the away-team matchday roster. But due to the then one-sub rule in association football, Coker anticipated not even making the proper team sheet. “When you get to where you’re playing, [as the 15th player on the roster] your job is to roll out a kit for the players that are starting,” Coker said.

After he’d done that, Coker was approached by West Ham manager Ron Greenwood and the injured Geoff Hurst. “Ade,” Greenwood said, “Get ready. You’re starting.”

“Oh my god,” Coker remembered thinking. “I was just totally dumbfounded.” Geoff Hurst, who Coker was replacing as the 9, gave him some encouragement, “Congratulations. I know you can do it.”

Coker’s confidence was further buoyed by captain Bobby Moore, who was the first active player up. “Go on, son,” Coker remembers Moore telling him. “I’ve seen you. I know you can do it.” The rest of the team followed, and Coker, who had less than an hour to process the moment, ran through what he describes as a range of emotions. “Just pretend you’re playing with the youth team,” Clyde Best remembers telling Coker. “Don’t be afraid. You can play in this league.”

As they took the field at Selhurst Park, Moore again was there to boost his teenage teammate. “Hey, I know what it’s like,” Moore said. “But just go out and do what you’ve done in training, because you can do it.”

“I thought, if he has that much confidence in me,” Coker said, “I better get up and come for it.”

In the 8th minute of the match, Coker sprang on a loose ball from a Hammers’ corner and sent a screamer past Eagles’ keeper John Jackson.

Coker’s debut embodies the environmental ethos Charles came from and strived to create wherever he went: family, the type of place where every person can contribute a verse. And when that cultural infrastructure exists, massive things can happen, like they did later that season, on April 1, 1972.

Of the football at the Boleyn Ground that day, Tony Pawson’s match write-up in The Observer includes that West Ham’s last-minute goal of a 2-0 win, “was tapped home by young Coker, whose transports of delight gave the game the happiest of endings.” The significance of that match, however, was more than full points for West Ham over Tottenham. When Hammer’s manager Ron Greenwood’s match card once again scratched Geoff Hurst for Coker and additionally crossed out Frank Lampard for Clive Charles, history was made.

That match was the first time a top-flight English side started three black players: Clyde Best, Ade Coker, and Clive Charles.

“It felt great,” Best told me. “Because we all knew that was the first time something like that had ever happened in English football. We were pleased to be given an opportunity to be the first three black players to be chosen. And it wasn’t that we couldn’t play, we could play, you know, we knew that we could play.”

“We really worked so hard, and it just so happened that that was the way [Ron Greenwood] picked the team because Ron always believed, when you’re ready, you’re in,” Ade Coker said of the day. “We were just playing football.”

For his part at the time, Charles had made his debut earlier in the season and saw the match as another day to get on the field and contribute. “I didn’t see myself as paving the way for others when I was playing, but I suppose we must have been,” Clive told Brian Belton, in East End Heroes, Stateside Kings. “I just didn’t think of myself as a black soccer player. I was just earning a living.”

Fifty years on, it’s impossible to put into perspective what Coker, Best and Charles did that day. “Because of our color people were going to have a go,” Clyde Best said. “We knew the most important thing was not to get involved. We had to be bigger than that. And let them know that we’re not afraid to come out here and play.”

I don’t know how much this may have come up throughout the years, because Clive seems to have been so focused on his players and their journeys first. “When I went to UP, when I met with Clive, when I made the decision [to go to UP],” said Keller, “there was never a thought process that I’m playing for a black coach who broke the color barrier.” What it comes down to for Keller, who has seen more than his share of locker room dynamics, is this, “I don’t care what color you are, what religion, what country you’re from. You’re a good guy [or] you’re not a good guy. Can you help us win or not? Nobody cares. Just come out and be a good person.”

I don’t care what color you are, what religion, what country you’re from.

That match, however, is just one monumental football moment involving a Charles. Clive’s older brother John was the first black player to play for West Ham. He also became the first black player to represent England, when, according to Roshane Thomas’s “John Charles: England’s First Black Player Who The FA Forgot,” for The Athletic, “On May 20, 1962, England Under-18 beat Israel 3-1 in Tel Aviv. John Charles started and scored.” That’s only part of it. The next year, John Charles played on the UEFA European Champion England side and captained West Ham to an FA Youth Cup.

Clive’s older brother John was the first black player to play for West Ham

This is why we need to ask, because the connections are many, and the opportunities are fleeting. I’ve tried to find what artifacts I can of Clive playing, mostly just unearthing short match highlights from England, like the April 1 match, and a clip where Clive, then captaining Cardiff City, sticks a penalty at Stamford Bridge. I’ve even been able to find a full indoor match when Clive was at Pittsburgh, where he slams home a left-footed power-play goal from the red line and then joins his team on the bench for a laugh and a smile. I’ve even seen a picture of Clive and John on the field together, a 1970 Getty Image from Chadwell Heath. And though Clive and John never played a first-team match together at West Ham, Bobby Howe witnessed both John and Clive Charles’s championship performances first-hand. ”Well, I’m older than Clive and I played with Clive’s brother John,” Howe said. “[John and I] were on the same youth team, the one that won the FA Youth Cup in ’63.”

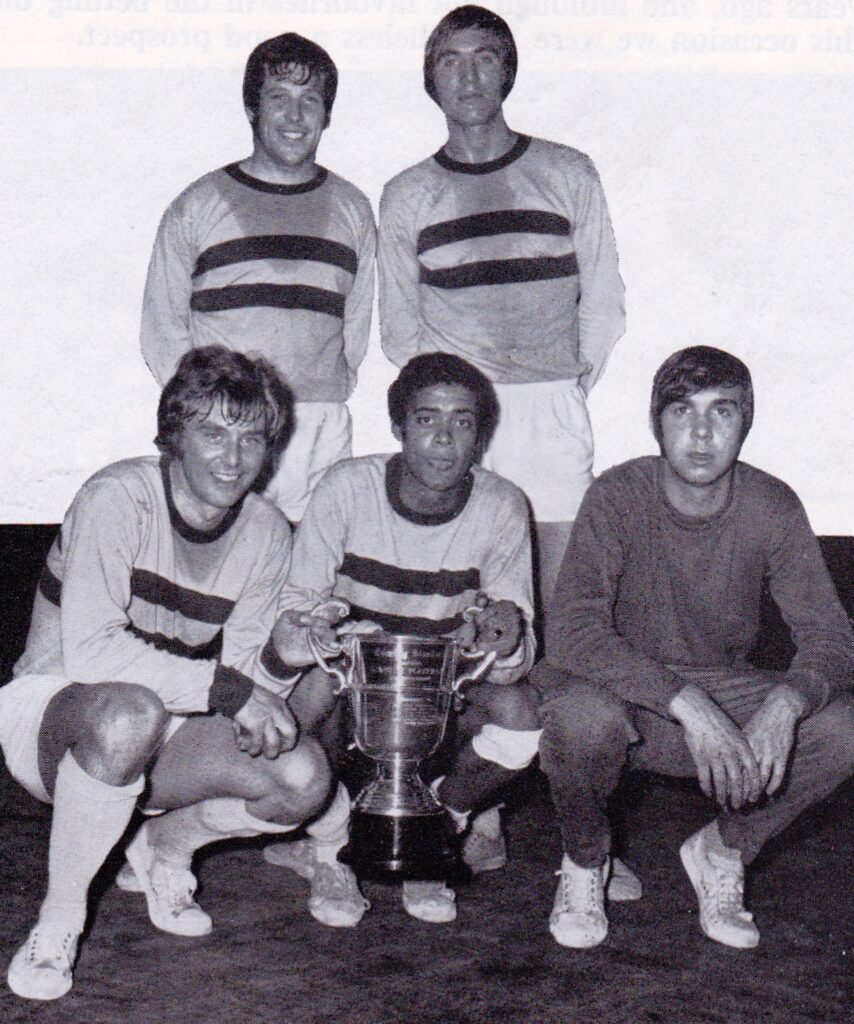

Howe was also the younger Charles’s championship-winning teammate when, in 1970, then-18-year-old Clive Charles was man of the tournament in the London 5’s. Clive scored both goals for the Hammers in their 2-1 final win against Tottenham. “That was played at Wembley,” Howe said of the one-night indoor tournament.

As a player, Clive was “very smooth, very fast and quick,” according to Howe. “He also had a tremendous amount of endurance. I remember when we’d do pre-season running in Epping Forest. We’d all start at the same time and the next time you’d see Clive was while he was waiting for you at the finishing line.”

“It was three of them,” Clyde Best confirmed. “We had Charlo, Billy Bonds, and another. Those three would take off, and you wouldn’t see them until the finish. One day Bobby Moore, Brian Dear, and a bunch of the old guys told Charlo he had to run with us.” Best laughed, “they knew when we got to the finish line, there’s no way any of us would be finishing in the top three.”

Yet, as a player, Clive was more than fitness. Teammates told me he could tackle and distribute. And his ability to read people and the game paved the way for his success on and off the pitch. “Well I know one thing about Charlo,” Clyde Best says. “We had an understanding when I’m playing. I knew when he was ready to deliver the ball to me, I would just go wide. He was an excellent passer. He had a sweet left foot and it will pick you up from 30 yards, 40 yards.”

As good as Clive was, in 1970s England, only one substitution was allowed per match. At West Ham, the left-back depth chart started with Frank Lampard, Sr, who, to this day, is still second on the Hammers’ all-time appearance list at 667. Playing time would not be easy to find as an Upton Park three.

In 1974, Clive moved to Cardiff City, where he would meet lifelong friends Bill Irwin and Willie Anderson. Clive was named captain, the first black player to do so for a top-division side. “That was the first time I really thought about the fact that I was a black player,” Clive told Belton. “The local newspapers made a big thing about me being the first black player to captain a League side. Until that point, I had thought about myself purely as a footballer rather than a black player.”

“Maybe it was because he was from West Ham.” That’s what Willie Anderson said when I asked about Clive being named captain at Cardiff City. Anderson himself was a swift, mercurial player. There’s a video out there of him, Clive, and Bill Irwin playing for Cardiff City away at Stamford Bridge, which was then on its 100th year as a football ground. Toward the end of the highlights, Anderson gets the ball about 45 yards from goal and weaves through two Chelsea players before the second brings him down in the box, and the captain Clive Charles steps up and converts from the spot.

“He came from West Ham,” Anderson said, “which was really the best place you can. He was a fullback, and his ball-handling and his attacking ability was kind of ahead of his time. But, you know, that’s how they played at West Ham. He’s really good on the ball. He’s really good at attacking, and crossing and he was quick. But he had a ton of skill. In those days, most fullbacks were just big bruisers. Clive just had a little bit more than that.”

“A good defender, very good left foot,” Irwin said of Clive as a player. “He could run all day–what you want out of your outside backs today, up and back.” All three Bluebirds would eventually leave Cardiff City to end up in the NASL, Anderson and Charles reuniting with the Portland Timbers in 1978, where Charles’s fitness and ahead-of-his-time overlapping would be an asset, though at times a challenge for the outside half on his side.

“Just a fantastic player,” John Bain said of playing with Clive in Portland. Bain is a Timbers legend. He ranks tenth all-time in NASL assists and 18th in total overall points. “Clive was an overlapping fullback who was suited to the modern game. A great left foot, and he could go forward. He could be playing right now.”

With a heavy influence from Europe, the ’70s NASL was, at least in playing style, somewhat static. “British-coached teams would normally play the 4-4-2,” Bain said. He added that “German-dominated teams would play with a sweeper,” a claim corroborated by Brian Gant: “Back in those days, the outside back didn’t come forward. He’d just stayed home and distributed with long balls to the front to the target player.”

“Clive was an overlapping fullback who was suited to the modern game. A great left foot, and he could go forward. He could be playing right now.”

John Bain, Portland Timbers Legend

Of course, Clive was different. “What you find with Clive,” Gant said, “was he’d always come forward and act like a winger. Whenever I played with Clive, I would just tuck inside, I’d leave that channel open as much as possible, knowing that, hey, if I’ve got the ball, I don’t even have to look. It’s coming. The train [Clive] is coming, and I’d just feed him through. Back in those days you didn’t have that, even in Europe. It was brand new.”

Playing in the ’70s NASL was different in many ways. One was the 35-yard line, which made offsides different than the conventional midfield line. In the NASL then, to help make the field bigger and allow attacking players to be closer to goal without worry of offsides, a forward could be 35 yards from goal and not be offsides, regardless of who would be between him and the goal. For crowds, it meant the possibility of more goals. For defenders, that extended the field because, if they went forward, they would have to recover not just to the midline but the extra real estate, all the way back to 35 yards from their own goal. Though most defenders opted for joining the attack by proxy of longball, Clive didn’t always.

“You had this huge, huge void in the middle of the park that was just big space,” Gant said of how the 35-yard line opened the field. “So if you’re an overlapping back, when you lost the ball, you didn’t retreat to the halfway line to form a back four, you had to retreat to the 35. So it was just this huge sprint to get back and forth. And Clive was just that player. He just he loved it. So he brought that into our team, which we never had, we never had a fullback that went forward like that. He was artful in what he did, he had a great left foot, he could land a ball anywhere you wanted,” said Gant.

According to Bain, that all just made Clive the perfect package for the 1978 NASL: “The 35-yard line made the field more spread out, but he would get back. I mean, he was pretty fit. He did his job, but [going forward] was a plus. He was just before his time,” Bain said. “He played for West Ham and their culture was always to play good soccer, where you played the game the right way.”

Clive’s ability to get up and back and provide service made the game easier and predictable for his teammates. “If he was out wide left, I would just start going to the back post and wait for that ball to come across, you know,” Gant said of tactics, something that echoes Clyde Best’s connection with Clive from West Ham to Portland: “We had an understanding. He had a sweet left foot and it will pick you up from 30 yards, 40 yards. I just collected it on my chest. He was able to do that, just a fantastic player. Today, if he was playing, he would have been a superstar.” Pele named Clive to his All-Time NASL team.

Notable and most likely foreshadowing of Clive’s future were the intangible things beyond his playing ability. “You always could hear his voice,” Brian Gant said. “He’d be coaching constantly. So you knew that was in him, you knew that eventually, that’s where he was going—he was going to go into coaching someday. He was always reading the game and reading situations. And if you played around him, it was great because he was coaching you all the time.” With this was Clive’s off-the-field ability to organize and include. Together with Graham Day, Clive quickly developed a reputation of bringing the team together, of including individuals around a joke, a meal, or an off-field activity.

Like many of the players at that time, making a go at indoor was an inevitable progression to keep playing. Clive was as successful an indoor player as he was outdoor. In the first MISL All-Star game, Clive was the one Pittsburgh Spirit player added to the 1980 Atlantic Division team, a roster voted on by the players in the league.

“Very consistent, very steady player, lefty,” his indoor coach John Kowalski recalled of Clive’s time in Pittsburgh. “He took some risks going forward, but he always knew to play for the team and do his job.” Kowalski described Charles as did his outdoor teammates: “Very accurate passer with great vision.” But it was even clear to Kowlaski then that Charles was destined to make his mark helping others through coaching. “As a person and as a player, Clive was very accountable and knew how to choose his sentences and words.”

When Clive played for Kowalski, he saw the Spirit skipper living the life that would be a logical next step.

While Kowalski was coaching the Spirit, he was also coaching in other places, including the University of New Haven with Dr. Joe Machnik. “I remember Clive being very curious about what I was doing and how coaching worked on the collegiate level,” Kowalski said. “We had quite a few conversations about being a coaching professional. He had the curiosity and the natural ability to transfer his knowledge to players.”

Playing soccer in the states in the early ’80s was difficult. Really, we have it so good now because so many then didn’t, but their love for the game, the same one we share now, drove them forward to build. Willie Anderson talks about playing on late-’70s then-Civic Stadium turf in Portland. “It was like cement,” he said. ”The Astroturf was so worn out. The hardest thing to do was trying to find the right pair of soccer shoes to wear on it. It was terrible.” And indoors, where many ended up, the conditions weren’t much better. “When Clive was in Pittsburgh,” Kowalski said, “we practiced at a place called the Ice Palace. Basically, it was a very, very cold ice hockey rink. Every morning, the team manager and another fellow would roll out the [turf, over the ice]. Then, at the end [of training] we had to pick it up because there was ice hockey practice afterwards”.

This is where our soccer comes from, from people doing what they did, so we had the MacMillanian opportunity. “The attitude and mentality of soccer players,” Kowalski said of the early ’80s in America, “was that we were looking to accomplish things for the sport, to establish soccer.” The conditions, less than ideal as they were, were secondary. “We’ve got to get this sport going. And somehow everybody was able to live with it.”

There’s so much I didn’t know about Clive before I started writing this. I knew he was a big deal, and I’m happy we’re talking about it here. I knew he built a program at a small college blocks from where I grew up–a program that is both women and men, that I went to his soccer camps as a kid, where my camp coach was Jeff Gadawski, where I was the camper of the week for the first camp he ran at the University of Portland. I still have the Nike bag I won, and I still remember all the Nike soccer balls piled together, with our assigned number on each. I knew that the soccer field there, in the summer months, was lush and green. I didn’t know, however, how the field got soggy when it rained or what it was like for his players, including Gary Osterhage, who remembers a moment where he saw vestiges of Charlo the three.

“We’re on our small game field that was inside the track,” Osterhage said of the University of Portland’s Philbrook Field, “And we’re practicing hitting balls as outside defenders up the line. It’s kind of muddy and rainy, and we’re slicing balls everywhere, and we can’t get them to the forwards. It’s like a 40-, 50-yard ball. So finally, Clive says, ‘Stop, can you guys not play a ball up the line? Is it that hard?’ And we’re like, yeah, we’re trying but you know, just kind of struggling a little. ‘Let me show you how,’ he goes. No joke, he’s got rubber boots on. The central defender plays the ball out to Clive, in his rubber boots, and he hits a 50-yard ball on a dime with his left foot, perfectly placed right on, probably [Scott] Benedetti’s thigh, or something. And he says, ‘If you can’t do that, then get off the field.’” Osterhage laughed, then he remembered the important context. “The best thing I ever heard him say,” which Osterhage still uses with his players to this day, “is ‘You have to earn the right to play.’ And that means when you step on the field, you know, nothing’s a given, they’re not going to give you anything, you know, you’ve got to basically perform and step up and show that you can play the game and then other people will respect your abilities. But you have to be able to earn that. And I share that with my players. I’ve carried that with me for the last 30 years.”

I knew Clive came from West Ham, but I didn’t know much else of what I’ve been able to share above.

We can also flatten time and find the commonalities bonded by the simple love of the game. Now, my son and I play one v one most mornings before school in our living room, with a size-1 ball to 2-foot PUGGs. Then, John Charles and his mates were in love with the same game, albeit infinitely more resourceful, in post-war East London. “After school, we’d all go home and have our tea, bread pudding or something like that,” John Charles tells Brian Belton in Johnnie the One, The John Charles Story, “and then we used to go over the [World War II] debris at the back of our houses, bombsites. We’d pull up turfs of grass and make the goals and we’d play football until it got dark. We used to do that every single night.”

Now, Tracy Nelson is the Director of Coaching for Portland Thorns Academy. Then, under her maiden name Osborn, she was ending her playing career at the University of Portland, and not wanting to stop playing. So Nelson did what one did in the mid ’90s: she faxed and she wrote letters. “I contacted the US Soccer Federation,” she said “and I asked them to fax me over the addresses of the federations in England, Australia, The Netherlands, and I think Sweden.” Armed with those addresses and a letter of recommendation from Clive, Nelson wrote them all, looking for an opportunity to keep playing, the irony now being, in large part because of Clive’s contributions to the game, if she were going through this process today she wouldn’t have to leave the country, let alone Portland.

After a season in Sweden, she found herself playing in England for Millwall. On May 4, 1997, Nelson became the first American woman to win the FA Cup. (And she’s only the second American ever, after Julian Sturgis lifted the Cup over a hundred years prior with his 1873 Wanderers teammates.) But that’s not the best part. “The FA Cup final was played at Upton Park,” Nelson said. “I knew walking in there that, oh my god, this is where Clive played.” The Lionesses’ 1-0 win over Wembley is the one time I’m OK saying Millwall took full points at West Ham. “It was super emotional, walking in there,” Nelson said of playing at the Boleyn Ground.

“But it was the best thing ever.”

This is part one of a three part series covering the legacy of Clive Charles.

Contributors

Billy Merck

Billy Merck signed his first professional contract for indoor soccer’s Portland Pythons, in a career that also included stops with the Utah Freezz, Cascade Surge, Lafayette Lightning, and Louisiana Outlaws. Billy played the three for Pacific University (Oregon) where he was an NAIA All-American and later inducted into their Hall of Fame in 2013; he holds the Boxers’ all-time career assist record, which he set in 1997. He also played and coached for FC Portland. After playing, Billy completed three masters’ degrees—including his MFA from McNeese State University and his PhD from Washington State University. He writes about soccer and lives in the Portland area with his wife and son. Twitter: @billymerck.

Illustration: Nick Iluzada

More of Nick’s work can be found at nickiluzada.com and you can follow him on Instagram at @kiluzada

TAGS