But he’s very nearly tearing the club apart in the process

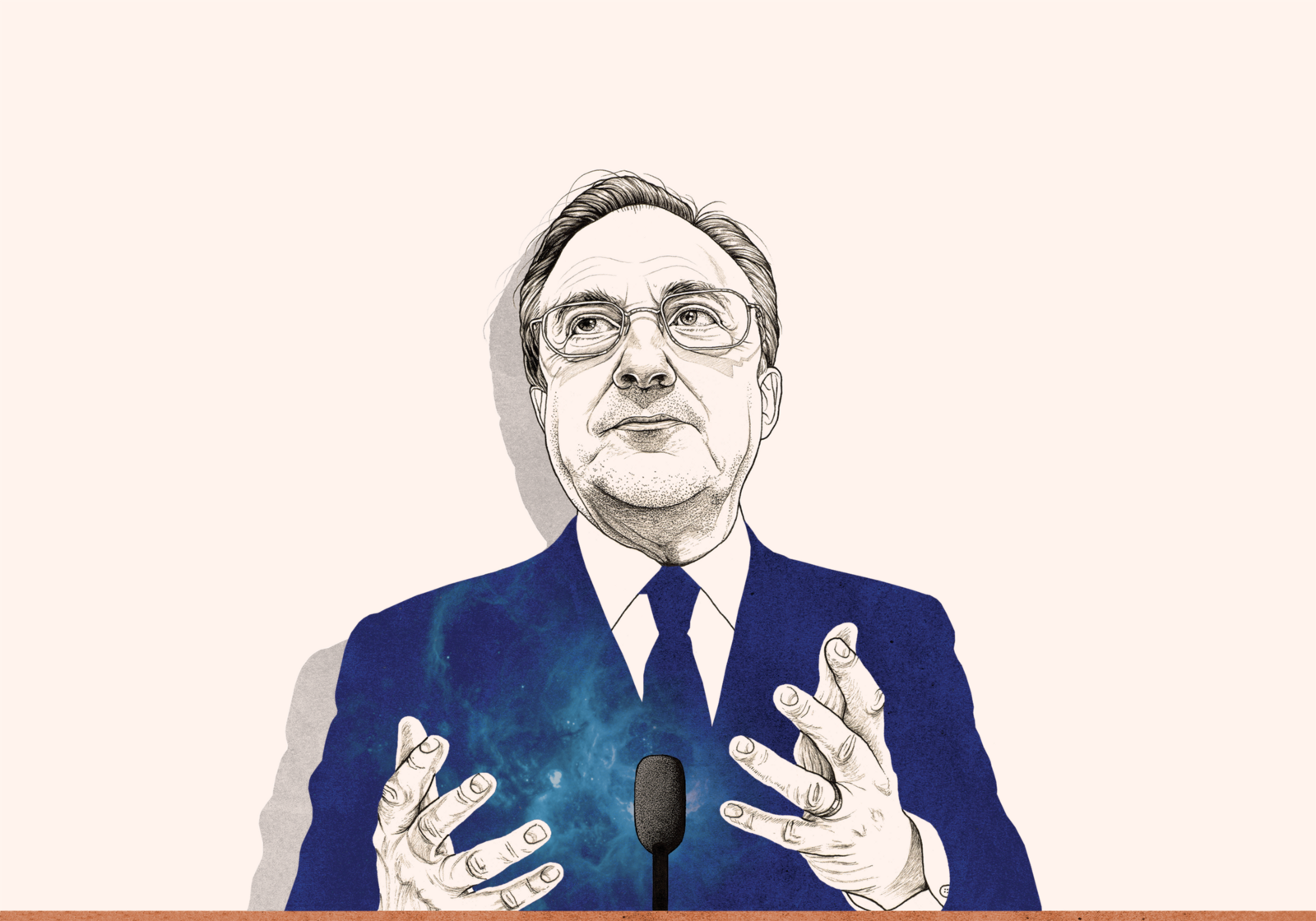

illustrations by Adam Cruft +

fan’s-eye-view commentary throughout by Real Madrid socio Nando Vila

I. Saturday, November 21, 2015

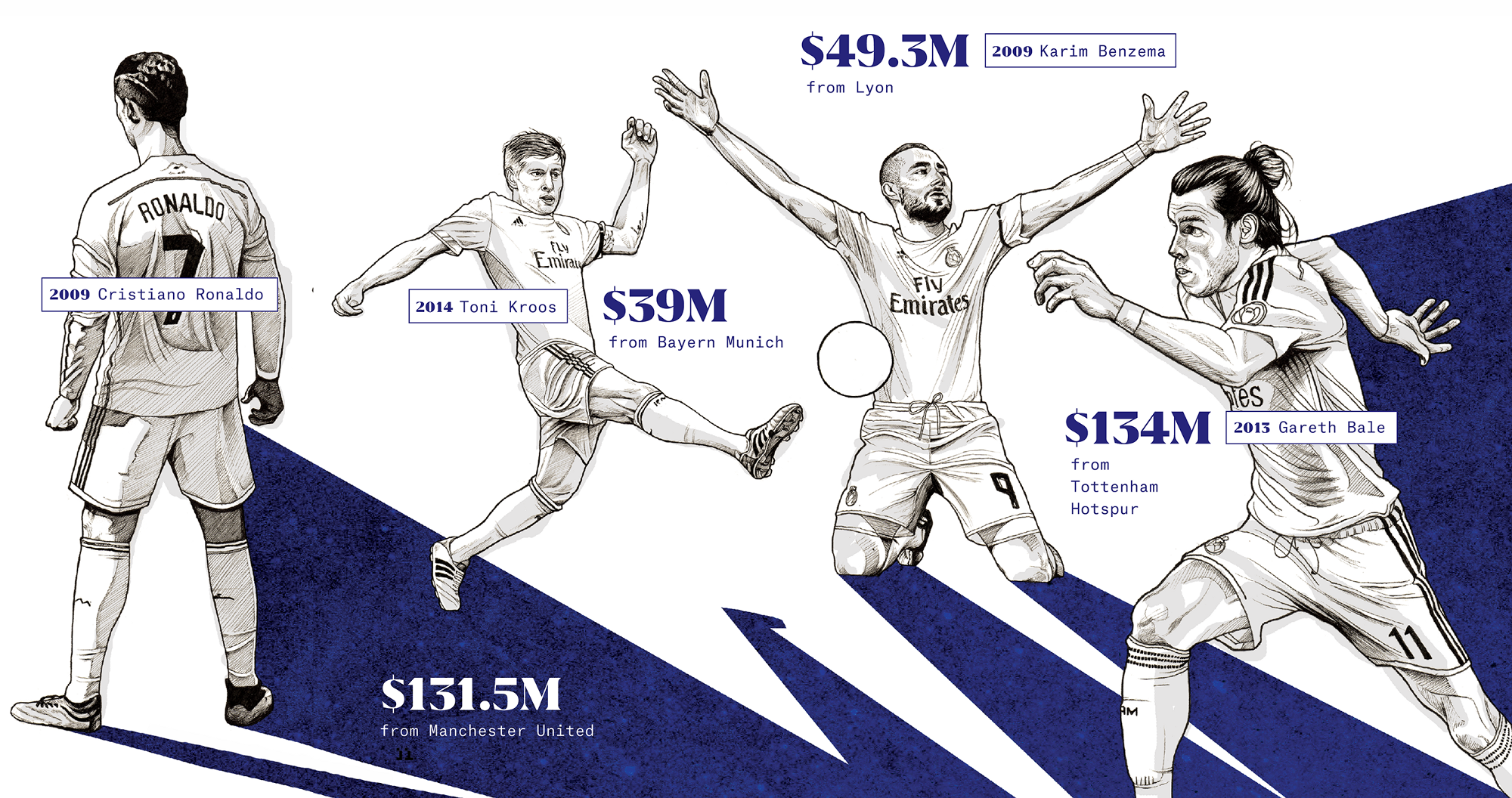

Florentino Pérez sits high in the front row of his executive box overlooking the Estadio Santiago Bernabéu. Mariano Rajoy, Spain’s president, sits to his right; to his left is the country’s minister of external affairs. The stadium is packed to capacity with more than 80,000 people, and they are joined by a global audience estimated to be in the hundreds of millions. All of these people are seeing what Florentino sees, his gaze directed stonily down onto the pitch, where the team he has personally and expensively assembled is losing heavily to its most bitter rival. Not just losing. Cristiano Ronaldo, Gareth Bale, James Rodríguez, Sergio Ramos, Toni Kroos, Karim Benzema, and the rest are being embarrassed by a score of three to zero. Worse still, Barça’s star player, Lionel Messi, not fit enough to start after two months out with a knee injury, is standing at the touchline, preparing to enter the match. As though his teammates need the help.

Florentino Pérez sits high in the front row of his executive box overlooking the Estadio Santiago Bernabéu. Mariano Rajoy, Spain’s president, sits to his right; to his left is the country’s minister of external affairs. The stadium is packed to capacity with more than 80,000 people, and they are joined by a global audience estimated to be in the hundreds of millions. All of these people are seeing what Florentino sees, his gaze directed stonily down onto the pitch, where the team he has personally and expensively assembled is losing heavily to its most bitter rival. Not just losing. Cristiano Ronaldo, Gareth Bale, James Rodríguez, Sergio Ramos, Toni Kroos, Karim Benzema, and the rest are being embarrassed by a score of three to zero. Worse still, Barça’s star player, Lionel Messi, not fit enough to start after two months out with a knee injury, is standing at the touchline, preparing to enter the match. As though his teammates need the help.

Softly at first, in a few isolated pockets of the stadium, a chant goes up. “Florentino, dimisión” (Florentino, resign). After Messi sets up Luis Suárez for Barça’s fourth goal of the game, the cries grow louder until it seems as though every single person in the crowd is calling for the president of Real Madrid Club de Fútbol to step down. Ronaldo, presented triumphantly by Pérez back in 2009, the club’s all-time leading goal scorer, winner of three Ballon d’Or trophies — they’re whistling Ronaldo, too, the bastards.

Florentino sits motionless in his plush seat. The bespectacled 68-year-old, clad in his usual gray suit and blue tie, his hair parted and smoothed as always, gives no indication that he hears them. Twice he has returned to save the club from deep financial and sporting crises. In his first term as president, Pérez oversaw the accumulation of Madrid’s galácticos into a side that won the 2002 Champions League. In his second, he built a team capable of halting Pep Guardiola’s Barcelona. Just 18 months earlier, a new generation of galácticos delivered the club’s 10th Champions League trophy, the long-awaited Décima. Madrid was now the richest club in the world, turning over $580 million, its stadium and training grounds among the world’s best. Without him, Madrid had been rudderless, leaderless. Pérez returned excitement, power, and ilusión to the Bernabéu. He acquired the best players, enriched the club, and returned Real Madrid to its rightful place as the world’s biggest and best. And yet there is the chanting, the whistling, the calls to resign.

“Can you imagine the pain that Florentino felt hearing the Bernabéu roar ‘Florentino, dimisión’ for someone who has got Real Madrid engraved in his infant heart?” says the author John Carlin, who shadowed Pérez during the year he researched his 2004 book, White Angels: Beckham, Real Madrid and the New Football, and who writes for El País and the Sunday Times of London.

“The truth is there is nothing that does more damage to Florentino than when the Bernabéu chants for him to resign,” echoes Joaquín Maroto, the former press chief for both Real Madrid and Pérez’s construction company Actividades de Construcción y Servicios, better known by the acronym ACS, and who now writes for Spanish sports paper AS. “He really feels that Madrid’s socios are part of his entourage, his world. When his own people reject him, chant for him to resign, he takes it badly.”

Admittedly, it has been a poor couple of months for Madrid and for Florentino personally. His decision to fire Carlo Ancelotti, the charismatic, Décima-winning coach, has been widely questioned. His decision to replace Ancelotti with the dour Rafa Benítez is not turning out well. There has been a string of very public embarrassments. Management bungled the departure of club legend Iker Casillas the previous June as well as its attempt to replace him with David de Gea from Manchester United.

Benítez was hired to provide a strong hand in the dressing room, to reorganize and motivate a group of players that had become accustomed to winning. Something had to be done to stop Barça from repeating the previous season’s treble of Champions League, La Liga, and Copa del Rey trophies. There have been some good performances, but there also have been signs of trouble. Even before the season started, Benítez irked Ronaldo by failing to declare, when asked, that his star player was better than Messi. He rowed publicly with club captain Sergio Ramos following a draw with Atlético Madrid in early October and then dropped $90 million transfer James Rodríguez to the bench. And in the main test — the only test, ultimately — Barcelona was still winning at the Bernabéu.

The solution to this is Rafa Benítez,” Pérez reads from a prepared statement at the Bernabéu on the Monday afternoon following the loss to Barcelona. “We signed him to turn things around. We think he is the right person. But we must let him work — not listen to those making up lies that the board doesn’t want him or the players don’t want him. He has a good relationship with the players, with the board, and me in particular. We understand the anger of fans after Saturday but ask for support for our players.”

The solution to this is Rafa Benítez,” Pérez reads from a prepared statement at the Bernabéu on the Monday afternoon following the loss to Barcelona. “We signed him to turn things around. We think he is the right person. But we must let him work — not listen to those making up lies that the board doesn’t want him or the players don’t want him. He has a good relationship with the players, with the board, and me in particular. We understand the anger of fans after Saturday but ask for support for our players.”

Twice in recent years Pérez has called similar press conferences to back a beleaguered coach, and in both cases he dismissed José Mourinho and then Carlo Ancelotti within months. Asked to confirm that Benítez would stay in the job long term, Pérez is less than firm with his answer: “I talk about this moment. I cannot say what will happen in the future. Nobody knows what will happen in six months.”

The following weeks bring more problems. The chanting resumes at the next home game. Reports emerge that a friend of Benzema has come into possession of a sex tape starring the French player Mathieu Valbuena and that the Madrid striker, a personal favorite of the president, played middleman in a plot to extort his teammate with Les Bleus. (Benzema remains banished from the French national team.) Madrid fields an ineligible player in the Copa del Rey and is thrown out of the competition. A defeat at Villarreal sees Benítez’s struggling side drop well behind Barça in the table. Meanwhile, everyone in Catalonia is laughing. On Friday, December 4, the Catalan daily Sport features Pérez on its cover with the headline “Annus Horribilis,” summing up what has been an awful 2015 for the leader of Barça’s rivals in the capital.

Two weeks later, on December 17, Florentino makes a rare media appearance, sitting for an interview on the highly rated, nightly sports radio show El Larguero. Earlier in the day, Barcelona’s win over Guangzhou Evergrande put the European champion into the final of the FIFA Club World Cup. That afternoon, Mourinho’s sacking by Chelsea reopened speculation that the Portuguese manager could make a swift return. Pérez reiterates his support for Madrid’s current manager, then answers a question about the calls for his own resignation that have been ringing round the Bernabéu.

Pérez typically considers his manager to be a nuisance who gets between him and the players, but Mourinho managed to seduce him. If the Special One hadn’t chosen to leave, he would still be managing Real Madrid. Now and forever. —N.V.

“The other day against Barcelona, there was a group of people who started chanting, ‘Florentino, dimisión,’ and it’s true that others joined in,” he says. “The next game, it was organized by some sporting papers in Madrid to burn down the Bernabéu. The same ultras started up the chant again, but the fans drowned them out and ended the issue. I can assure you that if I detect that the socios are not with me, I won’t just call elections. I will go. But they show me every day that they are with me. They want the best for Real Madrid. Self-criticism can reach a level that is destructive. The socios will remain the masters of their own destiny.

“I grew up in adversity,” he adds. “I’m not thinking about giving up and leaving. The day I go, it will not be because we lost 0–4 to Barcelona.”

The next home game proves to be one of the strangest in Spanish history. The smallest Bernabéu crowd of the season, 61,584, whistles Benítez and his players as they go down 2–1 to crosstown neighbor Rayo Vallecano. Helped by two red cards for Rayo players, Los Blancos score nine more goals to win 10–2. But even as Madrid completes the demolition, many in the home crowd applaud the rival team and whistle their own when Rayo nearly pulls one back. In the mixed zone after the game, Ramos is asked if he agrees with Pérez’s backing of Benítez despite the team’s poor form.

“If el presi says that, for sure it must be for a reason,” he says. “We are all just pawns here, and he is the king.”

II. Thursday, April 21, 1960

Florentino Pérez sits high in the recently rebuilt Estadio Santiago Bernabéu. A month after his 13th birthday, the boy is one of 125,000 people packed into the ground to watch Los Blancos take on the visiting Barcelona. This Clásico has something extra on the line: it’s the first time the two rivals have met in the semifinals of the European Cup.

Florentino Pérez sits high in the recently rebuilt Estadio Santiago Bernabéu. A month after his 13th birthday, the boy is one of 125,000 people packed into the ground to watch Los Blancos take on the visiting Barcelona. This Clásico has something extra on the line: it’s the first time the two rivals have met in the semifinals of the European Cup.

Florentino celebrates with his brothers, Ignacio and Enrique, his mother, Soledad, and his father, Eduardo, as Alfredo Di Stéfano opens the scoring in the 17th minute with a flying header, and again when Ferenc Puskás prods home from close range to make it 2–0 after half an hour.

The home crowd is enjoying the spectacle playing out beneath the halo of newly installed floodlights. Madrid on top — that is the proper order of things. Today’s home team has won each of the first four European Cups to date, dominating the competition with its host of global stars, including the Argentine center forward Di Stéfano, Hungarian attacker Puskás, and Spanish winger Paco Gento. With each goal, the players confirm that their team is the best in the world, and all around the Bernabéu, Madrileños twirl their white handkerchiefs in appreciation.

For fans like the young Pérez brothers, such dominance is normal. But as their father can tell them, it has not always been so. The club emerged peso-less from the Spanish Civil War. Its Chamartín ground had been hacked apart for firewood during the nationalist siege. In 1947–48, Real finished just two points off relegation while Barça won the title.

But club president Santiago Bernabéu had begun to use his charm and influence to transform Real Madrid into a champion. The Nuevo Estadio Chamartín opened in 1947, the year of Florentino’s birth. Four years later, his first visit to the ground left an imprint. “I have here a mark on my lip from that day,” he will tell Spanish newspaper ABC in 2013. “I was at the handrail below, and when they scored I ran to see my parents. I slipped on a step, banged myself, and I split open my lip. They fixed me up there and then, but I was left with the mark. A war wound from the stadium.”

In October 1953, a six-year-old Florentino saw his side beat Barça 5–0, setting it on the way to its first La Liga title in 21 years. Di Stéfano scored twice in that match, his debut for Madrid. His signing had been a political as well as a sporting coup, the Argentine superstar wearing white only because Spain’s sports minister, José Moscardó, who had fought alongside General Francisco Franco in the civil war two decades earlier, intervened to ensure the world’s best player did not join Barcelona instead.

Bernabéu himself had been decorated for fighting on the nationalist side in the war. He was more of a pragmatist than an ideologue, and he understood the importance of picking a winner. Soccer had become a useful tool as Franco’s fascist dictatorship slowly opened up to the world. In the same year that Madrid signed Di Stéfano, Franco sealed an agreement with U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower that allowed U.S. army bases in Spain. In 1955, Spain was admitted to the United Nations, and Madrid’s stadium was renamed in honor of the club’s president. The following year, Real Madrid won the first-ever European Cup.

The spectacle in Madrid was all part of the plan conceived by Bernabéu and his deputy, the public relations expert Raimundo Saporta. Using a mix of financial connections and showbiz smarts, they brought stars like Héctor Rial, Raymond Kopa, Puskás, and Didi to suit up alongside Di Stéfano. Together they beat the champions of France, Italy, England, Switzerland, Yugoslavia, Belgium, Hungary, Turkey, and Austria — all without losing a single match in four years of European competition.

But on this day in 1960, Barcelona’s Eulogio Martínez strikes 35 minutes into the game to make the score 2–1, and the crowd immediately becomes restless. Before the match, there had been an unusual feeling of apprehension in the capital. The Catalan side was on the rise, both at home and abroad. Barça had just clinched that season’s La Liga title, pipping Madrid on goal average after both teams finished with 46 points from 30 games. Barcelona had its own stars in Luis Suárez, the only Spaniard to win the Ballon d’Or, as well as Hungarians László Kubala and Sándor Kocsis. The squad was superbly organized and motivated by Helenio Herrera, a win-at-all-costs figure brought in from overseas with the specific aim of ending Madrid’s dominance.

Los Blancos had beaten Barça 2–0 at the Bernabéu the previous November but only weeks before this game had lost 3–1 at Barça’s recently completed Camp Nou, a stadium that almost matched their own ground in size and splendor. A worried Bernabéu responded by sacking Paraguayan coach Fleitas Solich and installing Miguel Muñoz, who had recently retired as a player for Real Madrid. Muñoz’s task was to prevent Barcelona from supplanting Madrid at the center of European football.

At 2–1 deep into the second half, the sides remain evenly balanced. The Pérezes grow nervous as Barça creates chances to equalize and take an advantage into the second leg at Camp Nou. But with three minutes remaining, Di Stéfano rises at the back post and heads the ball powerfully into the net. The crowd of 125,000 roars its approval. Madrid will go into the second leg in Catalonia with a solid lead, and the Pérezes walk back to their home in the middle-class neighborhood of Chamberí with the feeling that Barcelona’s challenge has been averted.

The following day’s nationalist ABC newspaper devotes 10 pages of coverage to the game, including what will become a famous black-and-white photo of Di Stéfano. The great man stands in the goal with his mouth agape, yelling toward the crowd with his hands over his head in celebration, white shirt and bald pate gleaming.

Diego Torres, who covers Real Madrid for El País in the present day, says that Madrid’s midcentury victories were widely seen as triumphs for a Spain that still believed itself to be a world power. “It has a lot to do with the history of Spain,” Torres tells me. “They feel predestined to rule the world — that is the legacy of the Spanish Empire. They are Madridistas; they cannot allow for Barcelona to dispute their place at the center of the world. It is a political problem that transcends football.”

Six days later in Barcelona, Madrid wins again, by the same score, to proceed to the final 6–2 on aggregate. The next month, Real Madrid will put on what is still regarded as one of the best performances by a club team, with Puskás scoring four and Di Stéfano three as Los Blancos hammer the German champion, Eintracht Frankfurt, 7–3 at Glasgow’s Hampden Park.

It is difficult to overstate just what such success meant to people like the Pérezes — a typical Spanish middle-class family in the postwar period, when times were tough for all but those with the best connections. Eduardo ran a drugstore called Shanghai, on Calle Hortaleza in the commercial center of Madrid. The family was comfortable but not wealthy nor attached to the regime. At Florentino’s school, the Catholic-run Escuelas Pías de San Antón, just off Madrid’s Gran Vía, he emulated Di Stéfano and Puskás in the concrete yard with his classmates, including his best friend and neighbor, Jerónimo Farré. Inside the Bernabéu, when their team was pulverizing all comers, people like the Pérezes felt as though they were in charge.

“The significance of that Real Madrid team was enormous,” says Sid Lowe, who writes about Spanish soccer for The Guardian and authored a book on the rivalry between Real Madrid and Barcelona. “Not just for Real Madrid fans but for many Spaniards. More than anything else, that team has always been seen as an expression of success in a period in which people in Spain did not expect to succeed.”

During Florentino’s formative years, Barça went 16 years losing every visit to the Bernabéu. In his book, Carlin writes that Florentino retained vivid memories of going to the stadium from around 1955, where he experienced “a euphoria so unbearably intense that he was condemned throughout the rest of his life to seek to recreate it.”

“It’s one of the key pieces in the Florentino jigsaw,” Carlin tells me. “As a little kid, he would go along to the Bernabéu at a time when Madrid were unchallenged at the peak of the game and all the greatest players were there. And it just left an indelible image — the greatness of it, the glamour of it, the victorious nature of the team. I think that idea just froze in his mind.”

III. Monday, July 24, 2000

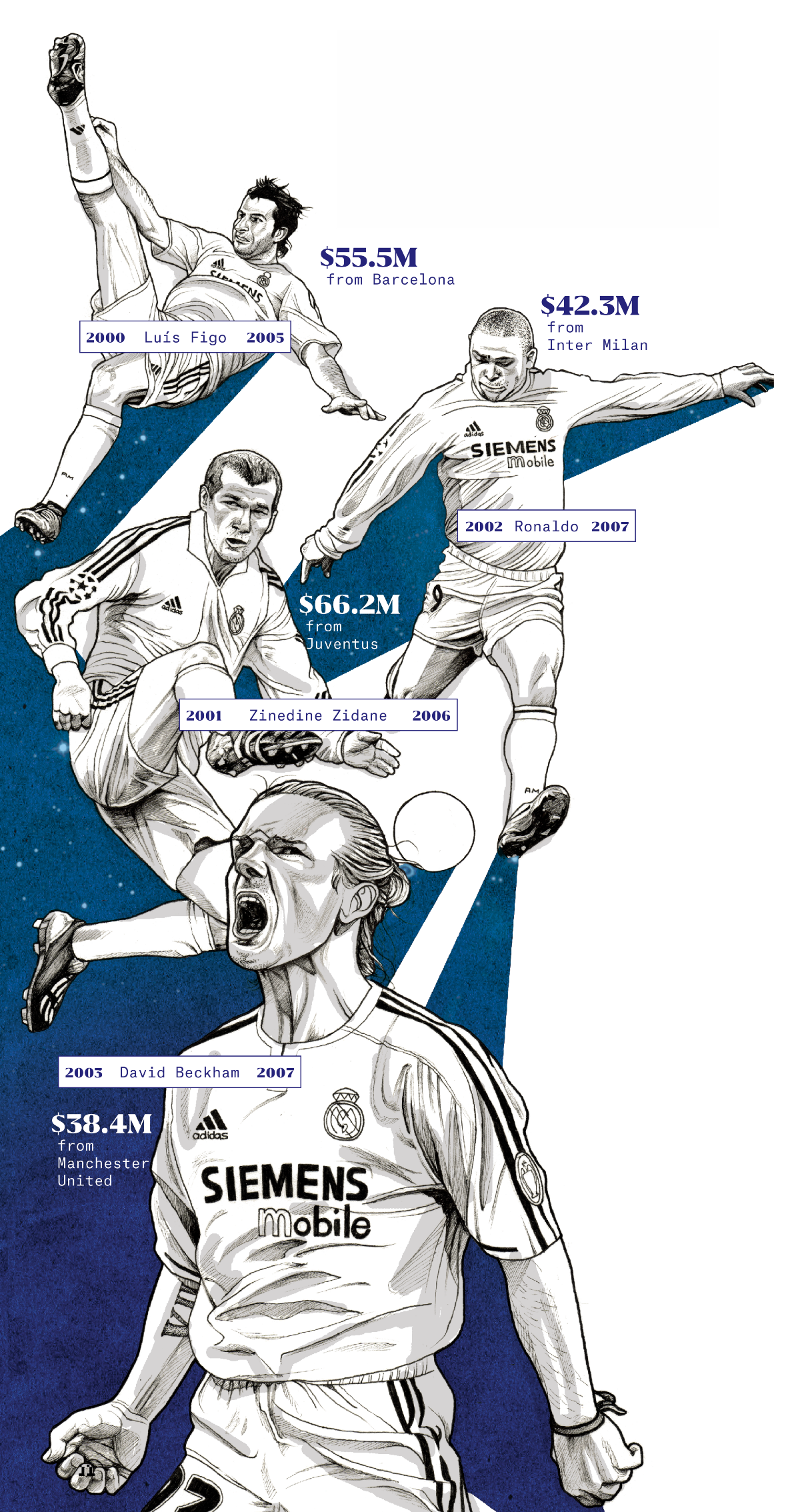

A nervous smile runs across the face of Real Madrid’s new signing as he holds up a white shirt with the №10 and his name — Figo — on the back. Days before the announcement, Luís Filipe Madeira Caeiro Figo had posed in a Barcelona jersey for the Catalan daily Sport and dismissed speculation that his future might lie with any other club. And yet here he is, Real Madrid’s newest star and, not coincidentally, the latest player to command the highest transfer fee ever paid.

A nervous smile runs across the face of Real Madrid’s new signing as he holds up a white shirt with the №10 and his name — Figo — on the back. Days before the announcement, Luís Filipe Madeira Caeiro Figo had posed in a Barcelona jersey for the Catalan daily Sport and dismissed speculation that his future might lie with any other club. And yet here he is, Real Madrid’s newest star and, not coincidentally, the latest player to command the highest transfer fee ever paid.

On the left side of the stage inside the trophy room at the Estadio Bernabéu is Alfredo Di Stéfano, now properly bald, posing for the photographers with the Portugal captain. It is the Madrid legend’s first official act since returning to the club a few days earlier as honorary president. To Figo’s right stands Florentino Pérez, 53, dressed in his trademark blue shirt, blue tie, and gray suit, accessorized today with the grin of a man who has just bought something expensive and dangerous. Three hours earlier, Pérez had deposited 10,270 million pesetas at La Liga headquarters — the player’s $55 million release clause plus 2.7 percent tax — rendering the Barcelona board powerless as its best player joined its biggest rival.

It’s hard to overstate how devastating this was to Barcelona. Not only was it the most expensive transfer in history by a long way — “Diez Mil Millones” seemed an utterly unthinkable price to pay for a player — but Figo was Barcelona’s captain and best player. The transfer gave Madrid a huge psychological edge over Barcelona for years to come. — N.V.

“It is with great personal satisfaction that I now present to all Real Madrid’s supporters, Luís Figo,” says Pérez. “And I do it here, in this room, and in front of Di Stéfano, as merits Figo, one of the best players in the world. In this house, the great players have always been taken to with affection. I want to tell Luís that I hope that he shows in this jersey, the jersey of the best club of the century, the same professionalism he has shown until now. I know that the fans are going to love you as we who form this board do.”

Figo does not smile, and like the president, he keeps his speech short.

“I want to say that I will try and dignify to the maximum the name of Real Madrid, and I hope to be as happy here as I was at Barcelona,” he says. “I can only promise to work and try and win everything. Thank you.”

Three weeks earlier, in the run-up to Real Madrid’s presidential election, Pérez had promised to bring Figo to the Bernabéu. Nobody had believed him. Incumbent Lorenzo Sanz had laughed at the idea: “Maybe Florentino will announce that he’s signed Claudia Schiffer next.” The player’s interview in Sport had calmed the mood in Catalonia. Less than two months earlier, Madrid had won its second Champions League trophy of Sanz’s five-year reign. Before Sanz, Madrid hadn’t been champion of Europe since Di Stéfano was still playing, more than three decades earlier. But the challenger sprung a huge surprise, and for the first time in five contested elections, the incumbent had been unseated.

The Sanz presidency was a chaotic mess, but the team was held together by Fernando Hierro and Raúl, two very strong leaders in the dressing room. The second Champions League title came at the end of a season in which the team had been in 15th place after 15 rounds in La Liga. Vicente Del Bosque replaced John Toshack on an interim basis and managed to save the season by guiding Madrid to success in Europe. — N.V.

It was the culmination of a plan that had taken many years to come together. Five years earlier, Sanz had beaten Pérez by just 480 votes. This time Pérez had been sure not to let that happen, dividing his time between running his construction company, ACS, and planning for the next election. In addition to holding regular discussions with advisers and friends, Pérez had surveyed Madrid’s socios — the electorate — to determine which players they most wanted to see at the club.

A former journalist named Joaquin Maroto was one of those advisers. He had given up his career as a reporter when Pérez personally hired him to be ACS’s director of communications.

“Florentino was the one who said, ‘No, we must go for Figo,’” Maroto tells me. “Because we do not just need a player who generated excitement in our team but who would also generate chaos in our rival.”

Figo was both Europe’s top player and the symbol of the Barcelona side. The right-sided playmaker had appeared in 172 La Liga games for the Blaugrana, scoring 30 goals and winning two league titles, two Copa del Rey trophies, and a Cup Winners’ Cup. He had also starred at Euro 2000. In addition to being the best, Figo looked like Pérez’s vision of a Real Madrid player: he was handsome, stylish, and elegant, and he bore himself nobly both on and off the pitch. It was this image that Pérez wanted to bring back to the Bernabéu. Sanz was a sleazy character, a nuevo rico who lacked class and culture. He did not represent the gentlemanly conception many Real Madrid socios had of the club, and he was also a poor manager of its finances. By the end of his tenure, Madrid was almost bankrupt.

Pérez’s path to this moment had little to do with soccer. After completing his compulsory military service and graduating from Madrid’s School of Civil Engineering, he taught at his alma mater for three years, but he had ambitions to do much more. In 1973, at the age of 26, he became director general of Spain’s Asociación Española de la Carretera (AEC), a highway industry lobby group. Three years later, his mentor at AEC, Juan de Arespacochaga, who had become mayor of Madrid, hired Pérez to run the city’s rapidly growing sanitation service. Pérez thereby became the youngest city councillor in the country’s history. In 1979, with Spain transitioning to democracy, the 32-year-old was a fast-rising star in the right-wing political party led by Prime Minister Adolfo Suárez, well set for a government position if Spain’s electorate had not chosen the Socialist Party in the 1982 general election.

“Florentino’s true vocation was for politics,” says Torres. “He has said that. But he discovered that the more you go out into the spotlight, the weaker you are. The real Florentino always acts in the shadows. The real Florentino is not the one you see in his public appearances.”

The real Florentino diverted his energies to the private sector. In 1976 he and Farré launched the Guía del Ocio, a guide to nightlife in Madrid, but that was no way to get rich. In 1983 he bought a small, bankrupt construction firm called Construcciones Padrós for just one peseta. Seventeen years later, the company had grown into a conglomerate called ACS, with 27,000 employees and an annual turnover of more than half a billion pesetas. The company won lots of contracts, especially for the construction of new roads, that were awarded by the ruling conservative Partido Popular, some of whose leading members Pérez had befriended during his early days in politics.

“Florentino’s business success had a lot to do with his short time in politics after the end of the dictatorship, when democracy came back,” says Thilo Schäfer, a German journalist based in Madrid who interviewed Pérez four times for the Financial Times in the early 2000s. “Every construction businessman wants to have good political contacts. He has done that. He is extremely astute, made some clever moves, swallowing other companies and enlarging ACS. By the time he became Real Madrid president, they were already one of the biggest building companies in Spain.”

Pérez was also successful in his private life. In 1970 he met 21-year-old María Ángeles Sandoval, known as Pitina, who worked at the Corte Inglés department store and who also came from a middle-class background. The young couple married eight months later and soon had three children. In 2000, the two still lived in a relatively modest house in Chamberí, close to the Bernabéu, with Pitina running her own sewing accessories shop nearby.

“He always had the dream of being Real Madrid president,” Maroto tells me. “When he met his wife, Pitina, he made her a Real Madrid socio. He had 29 season tickets in the Bernabéu’s Tribuna Preferencia, for him and all his family — his brothers, his brothers- and sisters-in-law, his parents, his children, his grandchildren. He took care of paying for all those tickets. Whenever a new member of the family was born, they were immediately made a member of Real Madrid.”

For the July 2000 Real Madrid presidential election, Pérez made use of his political instincts. He understood that Madrid fans had enjoyed their recent victories but that they craved something more — something like a return to the Madrid teams of the 1950s. He convinced them he was serious in his bid to acquire Figo by vowing to pay for the season tickets of all 70,000 club members should he fail.

“The notion of señorío — chivalrous, gentlemanly nature, elegance — that was what he wanted to bring back,” says Carlin. “That was his dream, the ilusión, to create a team which would win everything, like the Gento-Di Stéfano-Puskás team did, and also just captivate the world by the beauty of their play.”

The move was also calculated to wound Barcelona. At 27, Figo was at the peak of his career, and he felt undervalued by the Barcelona board. Pérez’s banking connections allowed him to raise the huge sum of money needed to pay Figo’s release clause and offer the player a much higher salary than Barça could afford.

New Blaugrana president Joan Gaspart, who had pledged in his election manifesto to keep Figo, describes the deal as “immoral,” but Figo tells local reporters soon after making the switch that he has “a clear conscience.”

“I consider myself a man of my word,” says the player. “From the start, I knew I was going to play for Real Madrid. I want to apologize to Sport, but you must understand that as a professional, I could not reveal my situation. I feel sorry for my Barça teammates and above all their fans. But that is how life goes — and I already feel a Madridista.”

This stab at Barcelona has also been part of Florentino’s project from the start. While Madrid had won trophies in the 1990s, Barcelona had won hearts. Its “Dream Team,” coached by Johan Cruyff and featuring Pep Guardiola, Romário, and Hristo Stoichkov, became a serious challenger to Madrid’s status as Spain’s biggest and best-loved team.

While Catalonians rage at the trick that has been pulled on them, Madrid fans are enjoying a sense of superiority they have not felt for decades. “In 2000, the socios did not vote for Florentino so he would create something new,” says Torres. “Florentino presented Luís Figo as a guarantee that he had a formula to destroy Barcelona — taking away their great star, the best player in Europe. It was a great political blow, not a sporting project. He did not say he wanted Real Madrid to play in a certain way, or that he would work with the youth system, or have a certain transfer policy. He was acting as a politician. It was more a political project, the annihilation of the adversary.”

IV. Friday, September 30, 2005

Florentino Pérez steps up to the podium at Real Madrid’s newly completed Valdebebas training complex in the northern suburbs of the Spanish capital. “The history of Real Madrid has been linked to our stadium and our old Ciudad Deportiva,” he tells his 1,500 guests, including Madrid mayor Alberto Ruiz-Gallardón, regional president Esperanza Aguirre, Di Stéfano, Pitina Pérez, and Florentino’s childhood friend Jerónimo Farré, who now sits on Real Madrid’s board of directors. “The vision of a man like Santiago Bernabéu, who built in the 1940s our stadium and in the 1950s bought the Ciudad Deportiva and changed the path of our club. He built a sporting-economic model that has allowed us to be world leaders while remaining owners of our own club.” A huge video screen shows great moments from the club’s history, including European Cup–winning goals from Di Stéfano in 1960 and Zinedine Zidane in 2002. “We, the inheritors of this fortune, have the challenge of making Madrid also the best club of the 21st century. We are working to improve our beloved stadium. And today we have the best training facility ever built for a football club.”

Florentino Pérez steps up to the podium at Real Madrid’s newly completed Valdebebas training complex in the northern suburbs of the Spanish capital. “The history of Real Madrid has been linked to our stadium and our old Ciudad Deportiva,” he tells his 1,500 guests, including Madrid mayor Alberto Ruiz-Gallardón, regional president Esperanza Aguirre, Di Stéfano, Pitina Pérez, and Florentino’s childhood friend Jerónimo Farré, who now sits on Real Madrid’s board of directors. “The vision of a man like Santiago Bernabéu, who built in the 1940s our stadium and in the 1950s bought the Ciudad Deportiva and changed the path of our club. He built a sporting-economic model that has allowed us to be world leaders while remaining owners of our own club.” A huge video screen shows great moments from the club’s history, including European Cup–winning goals from Di Stéfano in 1960 and Zinedine Zidane in 2002. “We, the inheritors of this fortune, have the challenge of making Madrid also the best club of the 21st century. We are working to improve our beloved stadium. And today we have the best training facility ever built for a football club.”

The new training ground at Valdebebas, near Madrid’s Barajas Airport, measures 1.2 million square meters, 10 times the size of the old Ciudad Deportiva. In addition to 10 training pitches, it also houses dressing rooms, gymnasiums, office space, and a restaurant. A 6,000-seat stadium named after Di Stéfano is being built for Madrid’s Castilla youth team, and there are plans for a players’ residence, club museum, hotel and convention center, and even a theme park. It’s a remarkable development for a club that owed more than $575 million when Pérez came into office. But just as there had been a plan for getting the job, there had also been a plan for rebuilding the club.

José Ángel Sánchez, previously chief of Sega’s operations in southern Europe, joined in 2000 as Madrid’s head of marketing. Pérez instructed him to develop the club like a Hollywood studio, adding show-business sparkle to his boss’s financial muscle just as Raimundo Saporta had for Santiago Bernabéu five decades previously.

Figo’s arrival in summer 2000 was followed by that of Zidane in 2001, Ronaldo in 2002, and David Beckham, the world’s most famous player, in 2003. Madrid spent lavishly on transfer fees and salaries — more than any soccer club had ever spent. “We’re content providers, like a film studio — and having a team with Zidane in it is like having a movie with Tom Cruise,” Sánchez told the Economist in May 2002. Florentino regularly said this meant that the world’s most expensive players were actually the best value, and the inverted financial logic actually seemed to be working. The club’s 2005 accounts showed a profit of $43.2 million and bank debts of zero. Predicted income for 2006 was more than $432 million — up from $170 million in 2000 — and a record for any soccer club.

“Florentino came to the presidency after Lorenzo Sanz had made a complete dog’s breakfast of the thing as a business,” Carlin says. “He rolled up his sleeves and said, ‘Right, this is silly. We’re going to make money out of this. We’re going to provide glamour and Hollywood and success and excitement, and we’re going to transform that into serious money.’ And by golly, he did incredibly well on this front.”

Left out of Pérez’s speech this day is the main reason for the club’s newfound financial strength, which dates back to a deal completed in 2001.

Santiago Bernabéu had bought the land for the club’s training ground in the 1950s, when it was far outside the city; by 2001, it was prime real estate within the capital’s quickly growing financial district. Soon after Pérez’s election, the city council had rezoned the parcel for commercial use. The club sold the land and, after a complicated set of deals, emerged with outright ownership of two new towers on the site and 64.3 percent ownership of a third. For $145 million, the city council sold the land upon which a fourth went up. (ACS was involved in the construction of all four towers, which were named for Zidane, Figo, Ronaldo, and Beckham.) All told, the club made $404 million.

“His political contracts were crucial for this whole thing,” says Schäfer. “He had taken care of it even before they won the elections — talking with the mayor, the regional government, and the other political forces like the trade unions and even the left-wing Izquierda Unida. The only party to oppose it was the Socialists. The city gained something out of it, and it did not have to put in a single euro. It was obviously about helping the club reduce its debt, but it was not done with public money.”

It was the sale of real estate, not galáctico jerseys, that allowed Real Madrid to clear its debts in one stroke. The deal also allowed the club to purchase land near the airport for a new training ground and invest $106 million to modernize the Bernabéu. The Madrid socios who now sat in new, more comfortable seats warmed by powerful overhead heaters were also being sold the idea that they personally were back where they belonged. As in the 1950s, Madridistas were sitting in the world’s best stadium, watching the world’s best players. And it was Pérez who had made possible their deliverance.

The highlight of Florentino’s first five years as president was 2002, the year of the club’s 100th anniversary. The centenary celebrations were postponed when Deportivo La Coruña surprised Madrid by winning the Copa del Rey final at the Bernabéu. But success was to come in European competition. Madrid beat Champions League holder Bayern Munich in the quarterfinals, then progressed 3–1 on aggregate past Barcelona in the semis. The final brought Los Blancos back to Hampden Park, site of their 7–3 European Cup final win in 1960 over Eintracht Frankfurt. This time, the German opponents were Bayer Leverkusen, and Madrid once again dispatched them in galáctico style. Zidane’s volley is one of the most aesthetically beautiful goals in football history, and he scored it as Pérez, Di Stéfano, and Spain’s King Juan Carlos, a Blancos fan, looked down from the stands.

The highlight of Florentino’s first five years as president was 2002, the year of the club’s 100th anniversary. The centenary celebrations were postponed when Deportivo La Coruña surprised Madrid by winning the Copa del Rey final at the Bernabéu. But success was to come in European competition. Madrid beat Champions League holder Bayern Munich in the quarterfinals, then progressed 3–1 on aggregate past Barcelona in the semis. The final brought Los Blancos back to Hampden Park, site of their 7–3 European Cup final win in 1960 over Eintracht Frankfurt. This time, the German opponents were Bayer Leverkusen, and Madrid once again dispatched them in galáctico style. Zidane’s volley is one of the most aesthetically beautiful goals in football history, and he scored it as Pérez, Di Stéfano, and Spain’s King Juan Carlos, a Blancos fan, looked down from the stands.

Pérez had returned his club to the heart of the establishment. U.N. secretary general Kofi Annan caught a game at the Bernabéu in October 2003. Spanish president José María Aznar, a close ally of then U.S. president George W. Bush during the Second Gulf War in Iraq, was a lifelong Madrid socio and personally and politically close to Florentino, whose VIP zone at the Bernabéu, called the palco, became known as a place where powerful relationships were formed and deals got done.

“Quite often, Aznar brought along his wife, Ana Botella, who would become mayor of Madrid afterward,” Schäfer says. “Later, there was Socialist vice prime minister Alfredo Pérez Rubalcaba. There were many ministers, local councillors, and people from all parties — Socialists, leaders of the big trade unions. Football is not ideological, so you have people from unions who are staunch Real Madrid supporters. He tried to have good relations with everyone.”

In 2002, in his capacity as head of ACS, Florentino had pulled off a daring reverse takeover of Spain’s biggest construction company, Dragados, with help from the country’s most powerful banker, Emilio Botín of Banco Santander. The new combined company became one of the world’s largest construction firms.

The wedding of Florentino’s daughter, María Ángeles (the family calls her Cuchi), in September 2003 was another triumph. Figo and Madrid captain Raúl González attended the ceremony at the San Jerónimo el Real church, which is situated between the city’s famous Museo del Prado and Parque del Retiro, as did Madrid mayor Ruiz-Gallardón. President Aznar attended the wedding banquet that evening. Three months later, Pérez had the honor of pinning a medal commemorating 60 years as a Madrid socio onto the lapel of his father.

Barcelona’s downward slump made things even sweeter for Florentino. The Figo money from 2000 had been wasted, and the team finished fourth, fourth, and sixth in the subsequent seasons while shuffling through coach after coach. On his return to Camp Nou in November 2002, Figo was pelted with objects, including bicycle chains, golf balls, a whiskey bottle, mobile phones, rocks, screws, and a pig’s head, each missile making more evident the frustration of the home fans. The match ended in a scoreless draw, and Madrid went on to win the league title.

It seemed as though Florentino really had re-created the golden age he had basked in with his family a half century before. “With Real Madrid, the hard-nosed businessman becomes a kind of Don Quixote dreamer,” Carlin says. “In a way, he is regressing to that sort of infant state of wonder, that little kid who went to the Bernabéu when he was five or six years old. He has never entirely lost that.”

But the fairy tale soon began to unravel. Six months before the ceremony with his father, Pérez blundered by firing first-team coach Vicente del Bosque, who had been kept on from the Sanz years and won seven trophies in the first three seasons of the new regime. Florentino and Sánchez made their case to the public that the old-school coach, who had himself played for Madrid in the ’70s and now directed the side from behind a bushy mustache, was not glamorous enough to head up their Hollywood project. The summer of 2003 also saw the departure of key defensive linchpins Fernando Hierro and Claude Makélélé on the president’s say-so. Makélélé was replaced in the team by David Beckham, who was less tactically useful but much more marketable. Fans around the world wanted to bend it like Beckham. They had little interest in marking like Makélélé — and neither, it turned out, did anyone else on the squad.

But the fairy tale soon began to unravel. Six months before the ceremony with his father, Pérez blundered by firing first-team coach Vicente del Bosque, who had been kept on from the Sanz years and won seven trophies in the first three seasons of the new regime. Florentino and Sánchez made their case to the public that the old-school coach, who had himself played for Madrid in the ’70s and now directed the side from behind a bushy mustache, was not glamorous enough to head up their Hollywood project. The summer of 2003 also saw the departure of key defensive linchpins Fernando Hierro and Claude Makélélé on the president’s say-so. Makélélé was replaced in the team by David Beckham, who was less tactically useful but much more marketable. Fans around the world wanted to bend it like Beckham. They had little interest in marking like Makélélé — and neither, it turned out, did anyone else on the squad.

Del Bosque was not only successful as a coach but popular with fans from his days as a player. Most socios consider Pérez’s decision to get rid of him to be the president’s biggest mistake. — N.V.

“The model functioned while the team kept the base of the team built by Lorenzo Sanz,” Torres says. “Spanish players like Fernando Hierro, Raúl González, and Iker Casillas. Florentino always talked this down as he felt it took some credit away from him. Instead he signed Figo, Zidane, and Ronaldo — the best of that time. His project in that sense was pretty basic, pretty childish: ‘I want the best players.’ Anyone with the money to pay could have come up with that policy. That naturally grows your revenues, but it is not coherent from a sporting point of view.”

As the head of Spain’s largest construction firm eroded the foundation of his soccer team piece by piece, the structure began to wobble. Opponents with less talented players but more balanced tactics figured out how to beat the galácticos. Madrid lost the 2004 Copa del Rey final to Real Zaragoza and again exited the Champions League in the last 16. Los Blancos then lost six of their final seven La Liga games as unheralded Valencia, coached by former Madrid youth team coach Rafa Benítez, came from behind to win the title. The following season, Barça won its first championship in six years with a squad that included homegrown youngsters Xavi Hernández, Andrés Iniesta, and Lionel Messi. The political wind was also changing, with the Socialists regaining power. New president José Luis Zapatero was a confirmed Barça fan.

In the summer of 2004, with no realistic opposition, Pérez was reelected with a whopping 91 percent of the vote. But a year later, the “Florentino model,” as Madrid’s press had taken to calling it, was under intense scrutiny. His positions were coming under attack.

At the grand opening of Sports City, his inner politician is working overtime.

“In the last five years, Real Madrid has achieved many things,” he reminds his audience. “Nobody has won more trophies or had more Ballons d’Or in its ranks — an absolutely historical fact. But maybe there has been a certain loss of ambition after having won those seven consecutive trophies. That is why in the last few months we have put in place a plan to strengthen in all aspects. This summer the club made a great effort to complete a spectacular squad.”

That effort included signing Pablo García, Diogo, Júlio Baptista, Robinho, Sergio Ramos, and Jonathan Woodgate. Of these players, only Ramos will stick. Two months after the opening, Ronaldinho, a player reportedly rejected by Pérez for being too ugly, scores all three goals as Barça wins 3–0 at the Bernabéu. The home fans honor the Brazilian with a standing ovation. Three months after that, on February 27, 2006, with the team again out of the Champions League, having just been beaten at home by Mallorca, and its players rowing publicly in the press, Pérez calls another surprise press conference at the Bernabéu.

“This afternoon I have presented my resignation to the members of the board because I am convinced that it could be the wake-up call the club needs,” Florentino says. “I have thought deeply about this decision and see very clearly that it is an act of responsibility and coherence. During these years as president, I have always maintained that there are moments when a club like Real Madrid needs to be shocked into renovation. This principle must also apply to me personally. I am a Madridista since I was a boy, and I think this decision is an act of loyalty to the socios and an act of responsibility.”

“There was a self-destructive cycle with the megalomania of Florentino out of control,” says Torres, who was among the hundred or so reporters listening in shock. “He had felt himself infallible, all-powerful, and committed mistake after mistake until he felt obligated to resign.”

V. Thursday, January 24, 2013

“After the serious incident that happened today, I have broken my policy of not speaking about day-to-day matters at the club,” says Florentino Pérez, clad as always in his gray suit, blue shirt, and blue tie. He is standing in the Bernabéu’s VIP area, before a huge black-and-white photograph of the stadium in the 1950s. The cover story in that morning’s edition of Marca claimed that, the previous day, Pérez had met with José Ángel Sánchez, Iker Casillas, and Sergio Ramos at ACS headquarters, where his office looks out onto the four skyscrapers — named for galácticos from his original constellation — that now stand on Madrid’s old training ground. Madrid is 15 points behind Barcelona in the league table, and the squad is preparing for clashes with the Catalans in the Copa del Rey semifinal and with Manchester United in the final 16 of the Champions League. Over lunch, it was reported, the men had discussed bonuses for winning trophies at season’s end, a conversation that routinely takes place around this time.

“After the serious incident that happened today, I have broken my policy of not speaking about day-to-day matters at the club,” says Florentino Pérez, clad as always in his gray suit, blue shirt, and blue tie. He is standing in the Bernabéu’s VIP area, before a huge black-and-white photograph of the stadium in the 1950s. The cover story in that morning’s edition of Marca claimed that, the previous day, Pérez had met with José Ángel Sánchez, Iker Casillas, and Sergio Ramos at ACS headquarters, where his office looks out onto the four skyscrapers — named for galácticos from his original constellation — that now stand on Madrid’s old training ground. Madrid is 15 points behind Barcelona in the league table, and the squad is preparing for clashes with the Catalans in the Copa del Rey semifinal and with Manchester United in the final 16 of the Champions League. Over lunch, it was reported, the men had discussed bonuses for winning trophies at season’s end, a conversation that routinely takes place around this time.

They quickly agreed on a total sum of $11.4 million, wrote Carlos Carpio and Miguel Serrano, two experienced and well-connected reporters. Then the players had presented Pérez with an ultimatum: if José Mourinho remained as head coach the following season, a substantial number of players would seek to leave the club.

“The players told the president that this was not about a few players unhappy with not being picked,” the story continued. “It was about important players, starters, who would not lack offers from important clubs around Europe if Madrid were to put them on the market. They did not name names. There was no need to.”

Anyone with even a passing knowledge of the club knew that Mourinho had fallen out with many of his senior players. Long-serving captain Casillas, a three-time Champions League winner and the skipper of Spain’s 2010 World Cup–winning side, had been dropped from the team the previous month. Ramos had also been left out of big games, and other key players, including Mesut Özil, Karim Benzema, Marcelo, and Gonzalo Higuaín, were also displeased with their boss. The previous week, a postgame dressing room row between Mourinho and Cristiano Ronaldo had immediately found its way into the papers.

“It is totally false that at the lunch held with the captains and the director general an ultimatum about the coach was issued, or anything similar,” says Pérez at the Bernabéu. He then questions the propriety of the reporters: “There are ethical limits that everyone must respect.” The line brings a wry smile to the faces of many of the reporters present. Marca has generally supported Real Madrid, its president, and its players since the paper was founded in 1938. As Spain’s largest daily, it had been hugely influential in the decision of Pérez’s replacement, Ramón Calderón, to resign in January 2009, and again in Pérez’s ability to return to the position, unchallenged, the following June.

“There is often an assumption made in the UK that Marca is Florentino’s official mouthpiece,” says Lowe. “That is not fully true. But the media certainly plays an important role in the way that Florentino manages power, in the way he delivers messages and protects himself and the club as he perceives it.”

Upon his return, Florentino had presented himself as the only person capable of wresting control back from Barcelona, which had just won a treble in Pep Guardiola’s first season in charge. Further, Xavi Hernández, Andrés Iniesta, and the tiki-taka style of play they personified were the symbols of Spain’s newly successful national team, which had won its first international trophy in four decades at Euro 2008. Barcelona’s ascendancy came as Catalan nationalism emerged as a serious political force for the first time in decades, and Guardiola was a vocal supporter of his people’s right to self-determination, an idea that Spain’s new conservative president Mariano Rajoy refused to entertain. Perhaps most startling of all, Barcelona had come to the Bernabéu in May 2009 and won by a score of 6–2, the first time a visitor had scored six times against Real Madrid since 1931.

In April, Rajoy cut short a press conference by saying he had to go watch the first leg of Real Madrid’s Champions League semifinal against Manchester City on television. — N.V.

“It is obvious that Guardiola, as someone charismatic, a leader, was a very strong counterweight to Madrid,” says Torres. “Guardiola moves the axis of power in Spanish football, the center of Spanish football, from Madrid to Catalonia — for the first time in history. To lose that center was such a big trauma for a community that feels [it is] not just the center of Spain, but the center of the world.”

To wrest this center back to where it belonged, Florentino came into office and immediately spent almost $250 million on players including Xabi Alonso, Karim Benzema, Kaká, and Ronaldo, whose transfer from Manchester United made him the world’s most expensive. Together, they managed a whopping 96 points in their first season together, but Guardiola’s side won a second consecutive title with a record 99.

Madrid’s hopes of lifting the Champions League trophy in its own stadium, where the final was scheduled to be played, were dashed when Lyon bumped Los Blancos out in the final 16, and the home fans were spared the embarrassment of Barcelona doing it when Mourinho’s Inter Milan eliminated the Catalans in the semifinals. Inter went on to win the trophy, and the Special One remained behind in the Spanish capital to finalize the deal with Pérez that made him Madrid’s next manager. Mourinho did not play the type of exciting football the Bernabéu historically enjoyed, but he was a winner — and Madrid needed to win more than anything.

Gonzalo Higuaín missed a sitter in front of an open net that would have put Madrid through. One wonders how things might have been different had he scored that simple tap-in. — N.V.

“Can you imagine Florentino, deeply rooted in that Real Madrid mythology of the ’50s, his dream being to make that happen again — and Barcelona has acquired the mantle Madrid had in the ’50s?” says Carlin. “I think that kills him. Choosing Mourinho was an act of despair.”

Madrid was hammered 5–0 in Mourinho’s first Clásico, at Camp Nou in November. But the manager used the humiliation to gain more power inside the club, arguing that he needed full control in order to fully counter Guardiola. Florentino agreed and pushed aside sporting director Jorge Valdano, who saw himself a symbol of the club’s old-time values, when Valdano resisted.

The following April brought a deluge of Clásicos — four games against Barcelona in 18 days. Madrid won the Copa del Rey final with Ronaldo’s extra-time header, providing the first trophy of any kind since Florentino’s return to the club two years earlier. However, a 1–1 draw in the reverse La Liga fixture all but guaranteed the title for the Catalans. And Messi’s superb solo goal at the Bernabéu decided the Champions League semifinal, with Mourinho ranting at his postgame press conference about a conspiracy against the club and him personally.

Most people inside and outside Spain dismissed the conspiracy theories as paranoid nonsense. But by this stage, many Madrid members, including Florentino, accepted the coach’s ultraconfrontational approach. When Mourinho hooked his finger into the eye of Barça assistant coach Tito Vilanova after a match the following August — and then refused to apologize — Florentino never publicly censured him, and a banner reading “Mou, your finger shows us the way” was displayed at the Bernabéu throughout the autumn.

As a Madrid fan, I was shocked and embarrassed. Many of us couldn’t believe that Mourinho wasn’t fired on the spot. But Mourinho’s Reign of Terror was a very strange time at the club as Florentino consolidated his power. — N.V.

“The only thing that Florentino does not like about Mourinho is his way of playing football, his style of play,” says Torres. “But he likes everything else, which is more important than football. He likes how he manages the team, he likes him as a man, he likes him as a propagandist, a communicator — he loves that. What the socios want, and Florentino knows this, is to win.”

And Real Madrid did win the Spanish title that season, breaking the league record for most points (100) and most goals (121) in a campaign. Los Blancos also broke Guardiola. The Barcelona coach resigned, explaining that he was exhausted. Mourinho, meanwhile, signed a new contract, further strengthening his position in the capital. Pérez had seen his counterattacking style. It was a finger in the eye to those who longed for the creative brilliance symbolized by Di Stéfano and Zidane, but it was successful. And now he was signing up for more.

As he began the first years of his second term, Florentino the businessman was forced to adapt to trying circumstances. Spain’s construction bubble, which ACS had helped inflate, burst spectacularly. During the subsequent economic crisis, many previously feted business and political leaders were implicated in corruption trials. Pérez stayed clear of any serious legal problems, but his company was forced to diversify. Abroad, the focus was on new international markets, while within Spain the prize was public-service contracts in categories such as waste disposal and highway maintenance.

As he began the first years of his second term, Florentino the businessman was forced to adapt to trying circumstances. Spain’s construction bubble, which ACS had helped inflate, burst spectacularly. During the subsequent economic crisis, many previously feted business and political leaders were implicated in corruption trials. Pérez stayed clear of any serious legal problems, but his company was forced to diversify. Abroad, the focus was on new international markets, while within Spain the prize was public-service contracts in categories such as waste disposal and highway maintenance.

He also endured personal sorrow. Pitina died of cancer in March 2012 at the age of 62. Many of Spain’s social, business, and political elite, including former presidents Aznar and Zapatero, attended the funeral of the woman who had been a grounding presence in her husband’s life.

Real Madrid’s dressing room was another bastion of traditional values. Casillas had grown up within the club’s señorío ethos. Unhappy with the increasing influence of Portuguese superagent Jorge Mendes and critical of the club signing so many of his players — Pepe, Ricardo Carvalho, Fábio Coentrão, Ángel Di María, and Marcelo in addition to Ronaldo — Casillas defied Mourinho by maintaining friendships with his compatriots on the Spanish national team who played for Barcelona.

Through the fall of 2012, Madrid’s fans, players, and pundits were taking sides. One camp was headed by Pérez and Mourinho. The other was led by club captain Casillas and vice captain Ramos. Results were poor, with losses away to Getafe and Sevilla. One bright spot was the 2–2 draw in the season’s first Clásico, at Camp Nou.

Marca was taking an increasingly anti-Mourinho line. In September, the paper’s editor in chief, Roberto Palomar, wrote that the Portuguese was the kind of person who would flee a hit-and-run. In December, a young Radio Marca reporter named Antón Meana was harangued by the first-team coach and two assistants. Mourinho reportedly told the journalist, who had an inside line on locker-room gossip, that “in the world of football, me and my coaches are top, while in the world of journalism, you are a shit.”

All of this explains why the journalists assembled at the January 2013 press conference find Pérez’s complaints about Marca’s “ethics” rather humorous.

“I understand that the departure of someone from the club, the coach or the president, is an objective for someone, but to use a lie to achieve this does not seem ethical to me,” the president says. “I am here to say this very clearly: what was published is simply a lie.”

Marca editor Óscar Campillo sticks to the story and publishes images of text messages, purported to be from the players, that supposedly prove its validity. Ramos and Casillas keep quiet, but the club issues a statement on their behalf that reads, “We reject categorically the use of our names and those of the rest of the squad to back up information that we categorize as totally false. We would like to show our support for the figure of our coach, José Mourinho, to whom we owe the maximum respect.”

The statement does not seem credible, but then nobody — especially the club’s fans — can know who is really telling the truth. “You believe you know where things are coming from,” says Lowe. “But then, of course, your mind goes round in circles, thinking about the various Machiavellian possibilities.”

Amid the drama, Madrid manages to win that month’s Copa del Rey fixture with Barcelona, whose head coach, Vilanova, is absent, in New York receiving medical treatment for cancer. Despite this, Barça holds on to claim the league title with ease, matching the 100 points gained by Madrid the previous year. Borussia Dortmund eliminates Los Blancos in the Champions League semifinals, laying bare Mourinho’s reactionary tactics with a 4–1 first-leg victory in Germany. Real Madrid also manages to lose the Copa del Rey final at home in the Bernabéu to local rival Atlético Madrid. Before that game, Atlético had not won a derbi in 14 years, but Diego Simeone’s side embarrasses its richer neighbors with a 2–1 extra-time win.

Three days later, Mourinho departs by mutual consent, according to Pérez, his three years in Madrid ending in failure. Pérez remains, having betrayed his ideals to inflict temporary damage to Barcelona while simultaneously opening up deep and lasting fissures in his own club.

VI. Saturday, February 27, 2016

The succession of coaches led to Carlo Ancelotti and then Benítez. In both cases, Pérez continued to back his coaches — until he didn’t. The president supported Benítez during the final three months of 2015, but four days into the New Year, he sacked the coach and replaced him with Zinedine Zidane.

The succession of coaches led to Carlo Ancelotti and then Benítez. In both cases, Pérez continued to back his coaches — until he didn’t. The president supported Benítez during the final three months of 2015, but four days into the New Year, he sacked the coach and replaced him with Zinedine Zidane.

Firing Ancelotti was almost as unforgivable as firing Del Bosque. — N.V.

Zidane’s promotion from head coach of Madrid’s B team provided an immediate boost. Supporters enjoyed the sight of the former galáctico on the bench. Players from Cristiano Ronaldo to Sergio Ramos to Luka Modric appeared liberated, and they admitted that a change had been required. Initial results were positive, with the team hammering visitors Sporting Gijón, Espanyol, and Deportivo La Coruña.

The uptick does not last. Draws at Real Betis and Málaga allow Barcelona to open a gap at the head of the table. In late February, Zidane flunks his first big test when Atlético completely outplays Real at the Bernabéu. Pérez sits high in the stands beside Aznar as the chants of “Florentino, resign” again ring around the stadium, even louder than during the 0–4 Clásico defeat three months before. Adding to the weight of the moment is the fact that the game took place 10 years to the day since Pérez’s first resignation back in 2006.

“Next year it will change. There will be changes,” Zidane says afterward. “There could also be a change of coach. The challenge for the moment is, whatever happens, to keep going. We still have things to aim for this year.”

Zidane does not say that there could be a new president, but that is also a possibility.

The fractures opened up by Mourinho, so deftly handled by Ancelotti, are painfully open again. In the press area after February’s derbi defeat, Ronaldo defends himself from questions about his own form by criticizing the quality of some of his teammates. The superstar also targets the club’s medical staff — a weak point for Florentino. Madrid’s chief of medical services, Jesús Olmo, Farré’s son-in-law, is so unpopular with the players that they will not allow him to enter the dressing room on game days, but he has managed to keep his job.

Disgruntled fans are increasingly making themselves heard, too. A protest group called Movimiento Ámbar — “Amber Movement,” because adherents wear yellow — has become visible in the local media and at the stadium. It criticizes a September 2012 amendment to Madrid’s statutes, pushed by Pérez, stipulating that candidates for president must be Spanish citizens, members of the club for at least 20 years, and able to provide a bank guarantee of roughly $90 million. Pérez maintains that the requirements will safeguard the club from unscrupulous foreign owners, but others have pointed out that they drastically reduces his rivals for the job, and some fans are challenging the amendment in court.

Florentino has taken the club away from its socios. There’s simply no other interpretation. He raised the specter of a “sheikh” or “foreign interest” someday taking over the club to solidify his de facto dictatorship. Rumor has it that he made the change to 20 years in order to specifically block the candidacy of Vicente Boluda, who is one of the few club members with the financial clout to make the guarantee. — N.V.

“In his own mind, Florentino is the incarnation of Real Madrid,” says Carlin. “‘Le club, c’est moi.’ That is why he feels a sense of betrayal when the fans clamor for his resignation. But it is quite clear that he believes that he embodies the best of Real Madrid and that he is the man to lead Real Madrid back to that greatness of the 1950s. He is persevering doggedly away at that dream.”

That dream looks to be in deep trouble; late in the season, Barcelona seemed poised to repeat the previous season’s sweep and capture an unprecedented double treble. Off the pitch, investigations by the European Union and the local government have jeopardized a $449 million deal with Abu Dhabi’s International Petroleum Investment Company (IPIC) to further improve the Bernabéu. A land swap with the previous city council, giving the club extra space by the stadium, was not a problem when it was agreed back in 2001. But the city’s new mayor, antiestablishment figure Manuela Carmena, wants another look. Carmena is not a soccer fan; even worse for Pérez, she is critical of the chumminess between politicians and businessmen that was cultivated at the Bernabéu.

In this more difficult political and economic environment, success on the pitch became even more vital for Pérez. And suddenly, just when it seems the 2015–16 season is a write-off, Zidane’s team starts to click. The Frenchman surprises by benching $108 million creator James Rodriguez for the more defense-minded Casemiro, but the changes work. Ronaldo, now 31, starts to score more frequently, including in the return Clásico, which Madrid wins 2–1 at Camp Nou in April.

Meanwhile, Madrid keeps rolling in the Champions League. Despite a wobble in Wolfsburg in the quarterfinals, a Ronaldo hat trick sees off the Germans at the Bernabéu. The semifinals bring Manchester City. Zidane shows he is learning on the job, outwitting the much more experienced Manuel Pellegrini and masterminding a tight, tactical 1–0 aggregate victory. The Frenchman also reveals himself to have a handle on dressing room diplomacy, smoothing over intrasquad issues and calmly dousing media fires.

Many at the Bernabéu, and presumably the president, had expected the galáctico coach to get his stars to play beautiful football. Instead, a player prized for decorating games with individual moments of genius is emerging as a coach who values hard work and team ethic above all. “We suffered as you always do in a semifinal, but in the end we made it through,” Zidane says after the second leg.

Twelve straight wins to finish the La Liga season are not enough to reel in Barcelona, which takes the title by a point and wins the Copa del Rey final. But nobody at the Bernabéu calls for Florentino’s resignation now; all eyes are on Milan and the Champions League final on May 28 against Atlético.

Los Blancos do not shine at San Siro but they prevail nonetheless. Captain Ramos scores in his second consecutive final, and Ronaldo nets the winning penalty in the shoot-out. The noisy neighbors, Atlético, have been put back in their place, and Barça is overshadowed once again.

Less than six months after parachuting into the job, Zidane has led the team to its 11th Champions League title, the third of Pérez’s time in charge, and probably saved his boss’s hide.

Amid the Undécima celebrations, the abrupt sackings of both Ancelotti and Benítez are forgotten, and the sidelining of the highly marketable James does not matter. Zidane’s Madrid does not play spectacular soccer, but it is a winner, and that is all that counts. There is even a public détente between Florentino and Cristiano. Pérez says he would like to see the star player remain with Real Madrid for years to come and Ronaldo concurs. The victorious squad brings the trophy to Mayor Carmena at city hall, and there are smiles all round.

No price is too great for Real Madrid to remain Spain’s most powerful, most successful club. Difficult times often require decisive action and sacrifice. And there is only one man strong enough to make these decisions. Just ask Florentino. He’ll tell you.

Dermot Corrigan is an Irish football writer who lives in Madrid.

Adam Cruft is an illustrator who lives in London, England. He works predominantly in pen and ink.